Jensen Huang is not losing sleep over the possibility of writing a multibillion-dollar cheque to California.

The Nvidia chief executive, whose personal fortune has ballooned alongside the artificial intelligence boom, says he is unfazed by a proposed ballot initiative that could saddle the state’s wealthiest residents with a one-time 5% tax on their assets.

The proposed ballot initiative could cost Huang an estimated $7.75 billion if voters approve a one-time 5% tax on the assets of California residents worth more than $1.1 billion. Yet Huang says the idea has not troubled him.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

“We chose to live in Silicon Valley, and whatever taxes they would like to apply, so be it,” he said this week. “I’m perfectly fine with it.”

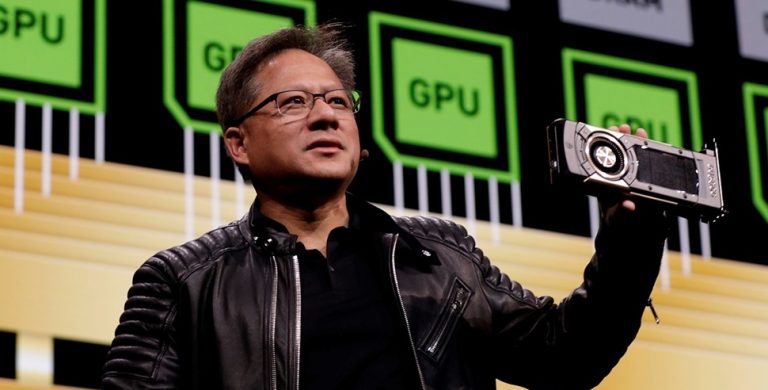

Those remarks landed at a moment when California’s relationship with its wealthiest residents is under renewed strain, shaped by fiscal pressure, political ambition, and the extraordinary concentration of wealth generated by the artificial intelligence boom. Huang, whose net worth Bloomberg puts at about $155 billion, sits at the center of that transformation. Nvidia’s rise from a niche graphics chipmaker to the most valuable company in the world has turned its co-founder into one of the richest individuals alive, almost entirely on the back of paper wealth tied to stock ownership.

The ballot initiative, introduced by a healthcare workers’ union and backed by lawmakers including Representative Ro Khanna and Senator Bernie Sanders, is designed to tap that concentration of wealth directly. It would apply to anyone worth more than $1.1 billion who resides in California as of early 2026, taxing their total assets, excluding real estate, regardless of whether those assets are liquid. Proceeds would be directed toward healthcare, public education, and food assistance at a time when California faces widening budget gaps following federal spending cuts.

Supporters estimate the tax could raise around $100 billion from roughly 200 individuals. In political terms, the argument is straightforward: a small group has benefited enormously from California’s ecosystem, and the state now wants a share large enough to materially shore up public services. In economic terms, the proposal is far more radical, cutting into unrealized gains and tying tax obligations to volatile asset values rather than income.

This is where the pushback from business leaders has been fiercest. Critics warn that founders and investors would be forced to sell large stakes in their companies to raise cash, potentially weakening corporate control and destabilizing firms whose valuations fluctuate wildly. Anduril co-founder Palmer Luckey has framed the proposal as a direct threat to founder-led companies. Venture capitalist Vinod Khosla has suggested it would accelerate an exodus of capital and talent.

The spectre of billionaire flight has long haunted wealth tax debates, and California’s proposal is no exception. Reports that figures such as Larry Page and Peter Thiel had considered leaving the state before the tax could take effect have only sharpened those fears, even as proponents point to studies suggesting that high-net-worth individuals are far less mobile than assumed.

Governor Gavin Newsom has already distanced himself from the idea, signaling opposition to state-level wealth taxes. If the initiative gathers the required 870,000 signatures to appear on the November 2026 ballot, Newsom and the legislature could still attempt to block it through the courts. Even if it survives those hurdles, it would almost certainly face years of legal challenges.

Against that backdrop, Huang’s stance reads less like complacency and more like a calculated signal. Nvidia’s success is inseparable from California’s talent ecosystem, particularly Silicon Valley’s dense concentration of engineers, researchers, and startup networks. Huang has repeatedly said that access to talent, not tax policy, drives where Nvidia operates.

“We work in Silicon Valley because that’s where the talent pool is,” he said, adding that the company establishes offices wherever skilled workers are available.

That view highlights a quiet fault line in the debate. For founders whose companies are deeply rooted in California’s innovation infrastructure, relocation is not a simple matter of changing addresses. For Nvidia, whose dominance in AI chips rests on decades of accumulated expertise and close ties to research institutions, Silicon Valley remains a strategic asset. A tax bill, even one running into billions, may be less consequential than weakening that advantage.

It also underscores how the AI boom has changed the politics of wealth. Much of the fortune accumulated by figures such as Huang exists on balance sheets rather than in cash. Taxing that wealth forces a reckoning over how societies value innovation, risk-taking, and the public goods that underpin private success. The proposal is for supporters, a corrective to an economy that has allowed extreme wealth to grow faster than public capacity. For opponents, it is a blunt instrument that threatens to punish success and introduce uncertainty into long-term investment decisions.

Huang has avoided that ideological framing. Instead, his comments suggest a pragmatic acceptance of California’s social contract: the same environment that enabled Nvidia’s rise may now demand a higher price of admission. And he appears content to let that debate play out.