AI Recreates 19th-Century Faces of Welsh Convicts Transported to Australia in the 1800s

Quote from Alex Bobby on August 20, 2025, 6:02 AM

Faces of Welsh Convicts Sent to Australia Recreated by AI

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is opening a new chapter in the way we connect with history. In Wales, researchers and volunteers have harnessed the technology to reconstruct the faces of 19th-century Welsh convicts who were transported to Australia for crimes that today might be considered minor misdemeanours. From stealing a handkerchief to trampling on a local aristocrat’s turnips, these men and women were sentenced to lives thousands of miles away from home, shaping not only their futures but also the history of modern Australia.

A Harsh Justice System

Between the late 18th and mid-19th centuries, more than 162,000 convicts were transported from Britain and Ireland to Australia. At least 1,000 of them were Welsh, with 60 coming specifically from Anglesey. The crimes that sealed their fate ranged from petty theft to livestock stealing—offence’s that highlight how harshly the justice system of the time treated the lower classes.

Among the documented cases were:

- John Hughes, sentenced to 10 years of transportation for stealing a handkerchief and glass.

- Hugh Hughes, who received a life sentence for stealing five sheep.

- William Williams, transported for seven years for taking 29 shillings from a boy.

The severity of these punishments was not arbitrary. Prisons in the UK were overcrowded, costly to maintain, and the colonies desperately needed labourers. Transportation solved both problems in one stroke, though at a devastating cost to those convicted and their families.

Bringing the Past to Life Through AI

For Roger Vincent, a volunteer guide at Beaumaris Gaol in Anglesey, the history of these convicts became a personal mission. After a holiday in Australia, he was struck by how deeply the convict legacy runs through Australian identity. Returning to Wales, he began combing through archives in Llangefni, piecing together the lives of those transported from his home region.

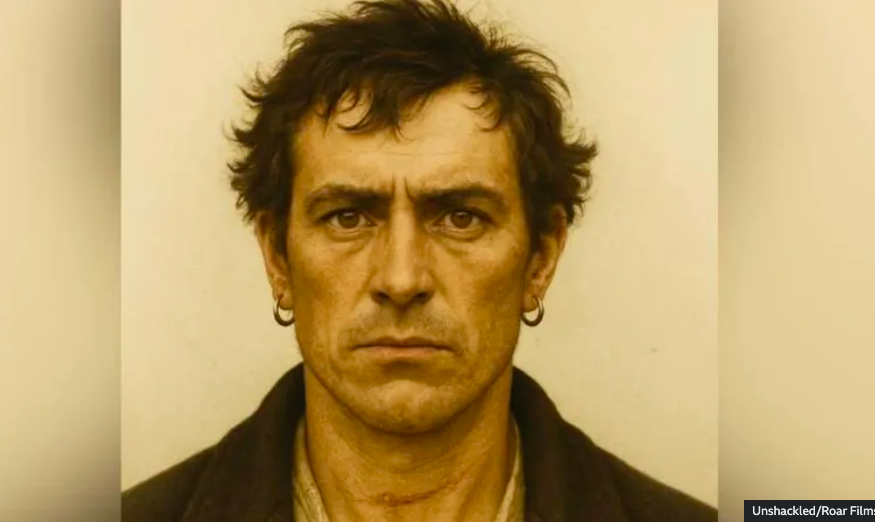

Now, through a collaboration with historians and AI specialists, the project has taken on a new dimension. Using detailed prisoner records, historical sketches, and where possible, photographs of modern descendants, researchers have generated AI reconstructions of what these convicts may have looked like.

These digital portraits are more than just images—they restore individuality to people long reduced to names and crimes in old registers. For descendants in both Wales and Australia, the reconstructions offer a human connection to their ancestors, sparking fresh interest in genealogy and history.

The Broader Context of Convict Transportation

Transportation was not unique to Wales. Across Britain, men, women, and even children were deported for crimes as simple as theft, poaching, or vandalism. But the Welsh cases highlight both the injustice of the system and the resilience of those who endured it.

Professor Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, a leading academic on convict history, notes that the perception of this legacy has shifted dramatically. Once seen as a “badge of shame,” convict ancestry is increasingly embraced as a point of pride, especially in Tasmania. “Australia’s origins as a settler society were based on criminal transportation,” he explains, “but now many Australians wear their convict heritage as a badge of honour.”

The shift is visible in public memory projects such as the Unshackled memorial in Hobart, Tasmania’s capital, which has become a top-rated tourist attraction. Such initiatives celebrate the stories of those who endured exile and highlight their role in shaping Australia’s early development.

Lives Rebuilt in a New World

For many transported convicts, the harshness of their sentences was compounded by the impossibility of returning home. The distance between Britain and Australia, combined with financial hardship, meant that most remained in the colonies for life. Yet many of them built new lives, started families, and contributed to the communities that would eventually become modern Australia.

Today, around 20% of Australians are believed to be descended from convicts, and in Tasmania the figure is thought to be closer to 50%. This widespread lineage helps explain why convict ancestry is increasingly celebrated rather than hidden.

Take the story of Ann Williams, transported from north Wales to Hobart in 1842 after being sentenced to 10 years for stealing. Her modern descendant, Caterina Giannetti, now living in Sydney, describes the discovery as both personal and profound:

“It’s really fascinating to know where you’ve come from, if there are any family traits or abilities to find out when they started. It’s very exciting to find out where your origins lay. And of course, it’s almost a badge of honour for an Australian to have a convict in their line.”

History Meets Technology

The use of AI to recreate the faces of Welsh convicts highlights the potential of new technologies in uncovering and reimagining history. These digital tools allow researchers to humanise forgotten individuals, offering insights that go beyond the dry language of historical documents.

For communities in both Wales and Australia, these reconstructions are more than academic exercises. They bridge a gap between past and present, fostering dialogue about heritage, identity, and justice. They also remind us that the individuals behind these stories were real people—flawed, fallible, and resilient—who endured extraordinary hardships.

Conclusion

The recreation of Welsh convicts’ faces through AI technology offers a moving intersection between history and innovation. By combining archival research with cutting-edge tools, researchers are giving voice and visibility to people who were long forgotten, helping us reconsider both the cruelty of the past and the resilience that carried these individuals through it.

What was once considered a shameful secret is now being reframed as a story of endurance, survival, and legacy. For Australians, especially Tasmanians, having a convict ancestor has become a point of cultural pride. For Wales, the project offers an opportunity to reflect on its own role in this chapter of history.

In the end, these AI-generated faces are not just images of convicts—they are windows into lives that continue to shape families, communities, and nations across two continents.

Meta Description:

AI technology has recreated the faces of 19th-century Welsh convicts transported to Australia. Discover their stories, harsh sentences, and lasting legacy on Welsh and Australian history.

Faces of Welsh Convicts Sent to Australia Recreated by AI

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is opening a new chapter in the way we connect with history. In Wales, researchers and volunteers have harnessed the technology to reconstruct the faces of 19th-century Welsh convicts who were transported to Australia for crimes that today might be considered minor misdemeanours. From stealing a handkerchief to trampling on a local aristocrat’s turnips, these men and women were sentenced to lives thousands of miles away from home, shaping not only their futures but also the history of modern Australia.

A Harsh Justice System

Between the late 18th and mid-19th centuries, more than 162,000 convicts were transported from Britain and Ireland to Australia. At least 1,000 of them were Welsh, with 60 coming specifically from Anglesey. The crimes that sealed their fate ranged from petty theft to livestock stealing—offence’s that highlight how harshly the justice system of the time treated the lower classes.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

Among the documented cases were:

- John Hughes, sentenced to 10 years of transportation for stealing a handkerchief and glass.

- Hugh Hughes, who received a life sentence for stealing five sheep.

- William Williams, transported for seven years for taking 29 shillings from a boy.

The severity of these punishments was not arbitrary. Prisons in the UK were overcrowded, costly to maintain, and the colonies desperately needed labourers. Transportation solved both problems in one stroke, though at a devastating cost to those convicted and their families.

Bringing the Past to Life Through AI

For Roger Vincent, a volunteer guide at Beaumaris Gaol in Anglesey, the history of these convicts became a personal mission. After a holiday in Australia, he was struck by how deeply the convict legacy runs through Australian identity. Returning to Wales, he began combing through archives in Llangefni, piecing together the lives of those transported from his home region.

Now, through a collaboration with historians and AI specialists, the project has taken on a new dimension. Using detailed prisoner records, historical sketches, and where possible, photographs of modern descendants, researchers have generated AI reconstructions of what these convicts may have looked like.

These digital portraits are more than just images—they restore individuality to people long reduced to names and crimes in old registers. For descendants in both Wales and Australia, the reconstructions offer a human connection to their ancestors, sparking fresh interest in genealogy and history.

The Broader Context of Convict Transportation

Transportation was not unique to Wales. Across Britain, men, women, and even children were deported for crimes as simple as theft, poaching, or vandalism. But the Welsh cases highlight both the injustice of the system and the resilience of those who endured it.

Professor Hamish Maxwell-Stewart, a leading academic on convict history, notes that the perception of this legacy has shifted dramatically. Once seen as a “badge of shame,” convict ancestry is increasingly embraced as a point of pride, especially in Tasmania. “Australia’s origins as a settler society were based on criminal transportation,” he explains, “but now many Australians wear their convict heritage as a badge of honour.”

The shift is visible in public memory projects such as the Unshackled memorial in Hobart, Tasmania’s capital, which has become a top-rated tourist attraction. Such initiatives celebrate the stories of those who endured exile and highlight their role in shaping Australia’s early development.

Lives Rebuilt in a New World

For many transported convicts, the harshness of their sentences was compounded by the impossibility of returning home. The distance between Britain and Australia, combined with financial hardship, meant that most remained in the colonies for life. Yet many of them built new lives, started families, and contributed to the communities that would eventually become modern Australia.

Today, around 20% of Australians are believed to be descended from convicts, and in Tasmania the figure is thought to be closer to 50%. This widespread lineage helps explain why convict ancestry is increasingly celebrated rather than hidden.

Take the story of Ann Williams, transported from north Wales to Hobart in 1842 after being sentenced to 10 years for stealing. Her modern descendant, Caterina Giannetti, now living in Sydney, describes the discovery as both personal and profound:

“It’s really fascinating to know where you’ve come from, if there are any family traits or abilities to find out when they started. It’s very exciting to find out where your origins lay. And of course, it’s almost a badge of honour for an Australian to have a convict in their line.”

History Meets Technology

The use of AI to recreate the faces of Welsh convicts highlights the potential of new technologies in uncovering and reimagining history. These digital tools allow researchers to humanise forgotten individuals, offering insights that go beyond the dry language of historical documents.

For communities in both Wales and Australia, these reconstructions are more than academic exercises. They bridge a gap between past and present, fostering dialogue about heritage, identity, and justice. They also remind us that the individuals behind these stories were real people—flawed, fallible, and resilient—who endured extraordinary hardships.

Conclusion

The recreation of Welsh convicts’ faces through AI technology offers a moving intersection between history and innovation. By combining archival research with cutting-edge tools, researchers are giving voice and visibility to people who were long forgotten, helping us reconsider both the cruelty of the past and the resilience that carried these individuals through it.

What was once considered a shameful secret is now being reframed as a story of endurance, survival, and legacy. For Australians, especially Tasmanians, having a convict ancestor has become a point of cultural pride. For Wales, the project offers an opportunity to reflect on its own role in this chapter of history.

In the end, these AI-generated faces are not just images of convicts—they are windows into lives that continue to shape families, communities, and nations across two continents.

Meta Description:

AI technology has recreated the faces of 19th-century Welsh convicts transported to Australia. Discover their stories, harsh sentences, and lasting legacy on Welsh and Australian history.

Uploaded files:

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print