Colombia ban the sale of Pablo Escobar memorabilia of the Drug Lord

Quote from Alex Bobby on February 13, 2025, 5:16 AM

Colombia’s Congress Seeks to Ban Pablo Escobar Merchandise: A Nation Divided

A proposed law in Colombia’s Congress has sparked heated debate as it aims to ban the sale of merchandise that glorifies former drug lord Pablo Escobar. While supporters see this as a crucial step in erasing the myth of a man responsible for thousands of deaths, opponents argue that such a ban could harm livelihoods dependent on Escobar-themed sales.

The Lingering Shadow of Pablo Escobar

More than three decades after his death, Pablo Escobar’s name remains infamous both in Colombia and around the world. While the Medellín cartel leader was responsible for untold violence, his legacy has been mythologized through pop culture representations such as the hit Netflix series Narcos.

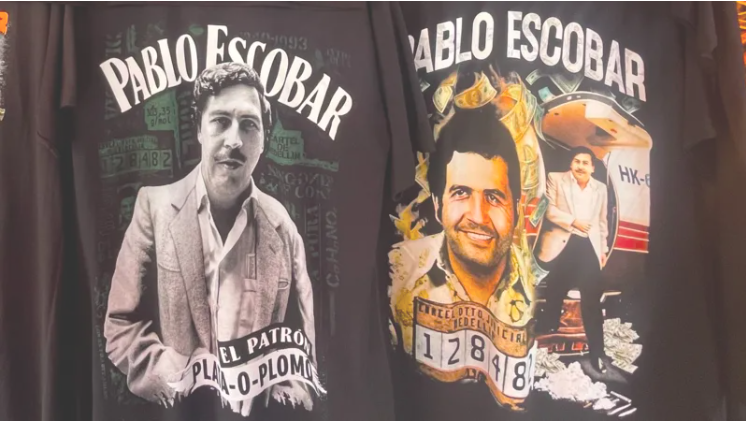

In Colombia, souvenirs bearing his face and name—T-shirts, mugs, keychains—are a common sight in tourist shops. Many visitors buy them as mementos of the country’s tumultuous history. However, critics argue that such items glorify a man who built an empire on bloodshed and destruction.

Gonzalo Rojas, whose father was killed in an Escobar-ordered bombing of Avianca flight 203 in 1989, is among those supporting the proposed law. “Difficult issues that are part of the history and memory of our country cannot simply be remembered by a T-shirt,” he states.

What the Proposed Law Entails

The bill, co-authored by Congress member Juan Sebastián Gómez, would prohibit the sale, use, and promotion of clothing or items celebrating convicted criminals, including Escobar. Violators would face fines, and businesses selling such merchandise could face temporary suspensions.

Gómez argues that Colombia has much more to offer than drug-related nostalgia. “The association with Escobar has stigmatised the country abroad,” he says, emphasising that the bill’s objective is to foster a more positive national image.

Divided Opinions: Livelihood vs. Ethics

Not everyone supports the ban. For many vendors in Medellín, especially in the revitalised Comuna 13 district, Escobar-related merchandise is a key source of income.

“This is terrible,” says Joana Montoya, a vendor who relies on Escobar souvenirs for at least 15% of her sales. “We have a right to work, and these Pablo T-shirts especially always sell well.”

Some shop owners claim Escobar products contribute as much as 60% of their revenue, making the ban a significant economic threat. Many vendors believe tourists will always seek Escobar memorabilia, whether legal or not.

On the other hand, some Colombians find the continued sale of such items deeply offensive. Shop assistant María Suarez, who feels uncomfortable selling Escobar-themed products, supports the ban. “We need this. He did awful things, and these souvenirs should not exist.”

More Than a Ban: A Need for Education

While supporting the bill, Rojas argues that Colombia must do more than prohibit merchandise—it must educate younger generations. He recalls a moment of disbelief upon seeing a stranger wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the words “Pablo, President.”

“There needs to be more emphasis on how we deliver different messages to new generations so that there isn’t a positive image of what a cartel boss is,” he explains.

To challenge the romanticised view of Escobar, Rojas and other victims launched narcostore.com in 2019. The website appears to sell Escobar-themed products, but when users attempt to purchase items, they are met with video testimonies from victims of cartel violence. The site has received 180 million visits, demonstrating a global interest in shifting the narrative.

Will the Law Pass?

The bill must pass four stages before becoming law, but it has already generated widespread discussion. Medellín’s mayor, who previously ran for president, supports the initiative, calling Escobar merchandise “an insult to the city, the country, and the victims.”

Comparisons have been drawn to other nations that reject the commodification of their dark pasts. “In Germany, you don’t sell Hitler T-shirts. In Italy, you don’t sell Mussolini stickers,” Gómez argues. “I think the most important thing the bill can do is generate a conversation as a country—a conversation that hasn’t happened yet.”

A Nation at a Crossroads

As the debate unfolds, the question remains: should Escobar’s image be erased from merchandise, or should it be left to the free market? For supporters of the bill, this isn’t about rewriting history—it’s about shifting the focus from glorification to remembrance, ensuring that Escobar’s victims are honoured rather than overshadowed by a manufactured legend.

For now, in the bustling tourist areas of Medellín, Escobar’s face remains on display. Whether that changes will depend on the outcome of a law that has already ignited a much-needed national reflection.

Colombia’s Congress Seeks to Ban Pablo Escobar Merchandise: A Nation Divided

A proposed law in Colombia’s Congress has sparked heated debate as it aims to ban the sale of merchandise that glorifies former drug lord Pablo Escobar. While supporters see this as a crucial step in erasing the myth of a man responsible for thousands of deaths, opponents argue that such a ban could harm livelihoods dependent on Escobar-themed sales.

The Lingering Shadow of Pablo Escobar

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

More than three decades after his death, Pablo Escobar’s name remains infamous both in Colombia and around the world. While the Medellín cartel leader was responsible for untold violence, his legacy has been mythologized through pop culture representations such as the hit Netflix series Narcos.

In Colombia, souvenirs bearing his face and name—T-shirts, mugs, keychains—are a common sight in tourist shops. Many visitors buy them as mementos of the country’s tumultuous history. However, critics argue that such items glorify a man who built an empire on bloodshed and destruction.

Gonzalo Rojas, whose father was killed in an Escobar-ordered bombing of Avianca flight 203 in 1989, is among those supporting the proposed law. “Difficult issues that are part of the history and memory of our country cannot simply be remembered by a T-shirt,” he states.

What the Proposed Law Entails

The bill, co-authored by Congress member Juan Sebastián Gómez, would prohibit the sale, use, and promotion of clothing or items celebrating convicted criminals, including Escobar. Violators would face fines, and businesses selling such merchandise could face temporary suspensions.

Gómez argues that Colombia has much more to offer than drug-related nostalgia. “The association with Escobar has stigmatised the country abroad,” he says, emphasising that the bill’s objective is to foster a more positive national image.

Divided Opinions: Livelihood vs. Ethics

Not everyone supports the ban. For many vendors in Medellín, especially in the revitalised Comuna 13 district, Escobar-related merchandise is a key source of income.

“This is terrible,” says Joana Montoya, a vendor who relies on Escobar souvenirs for at least 15% of her sales. “We have a right to work, and these Pablo T-shirts especially always sell well.”

Some shop owners claim Escobar products contribute as much as 60% of their revenue, making the ban a significant economic threat. Many vendors believe tourists will always seek Escobar memorabilia, whether legal or not.

On the other hand, some Colombians find the continued sale of such items deeply offensive. Shop assistant María Suarez, who feels uncomfortable selling Escobar-themed products, supports the ban. “We need this. He did awful things, and these souvenirs should not exist.”

More Than a Ban: A Need for Education

While supporting the bill, Rojas argues that Colombia must do more than prohibit merchandise—it must educate younger generations. He recalls a moment of disbelief upon seeing a stranger wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the words “Pablo, President.”

“There needs to be more emphasis on how we deliver different messages to new generations so that there isn’t a positive image of what a cartel boss is,” he explains.

To challenge the romanticised view of Escobar, Rojas and other victims launched narcostore.com in 2019. The website appears to sell Escobar-themed products, but when users attempt to purchase items, they are met with video testimonies from victims of cartel violence. The site has received 180 million visits, demonstrating a global interest in shifting the narrative.

Will the Law Pass?

The bill must pass four stages before becoming law, but it has already generated widespread discussion. Medellín’s mayor, who previously ran for president, supports the initiative, calling Escobar merchandise “an insult to the city, the country, and the victims.”

Comparisons have been drawn to other nations that reject the commodification of their dark pasts. “In Germany, you don’t sell Hitler T-shirts. In Italy, you don’t sell Mussolini stickers,” Gómez argues. “I think the most important thing the bill can do is generate a conversation as a country—a conversation that hasn’t happened yet.”

A Nation at a Crossroads

As the debate unfolds, the question remains: should Escobar’s image be erased from merchandise, or should it be left to the free market? For supporters of the bill, this isn’t about rewriting history—it’s about shifting the focus from glorification to remembrance, ensuring that Escobar’s victims are honoured rather than overshadowed by a manufactured legend.

For now, in the bustling tourist areas of Medellín, Escobar’s face remains on display. Whether that changes will depend on the outcome of a law that has already ignited a much-needed national reflection.

Uploaded files:Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print