Report: Cuban Prisoners Forced Into Labour to Produce Charcoal and Cigars for Europe

Quote from Alex Bobby on September 16, 2025, 5:07 AM

Prisoners in Cuba Forced Into Labour for Exports to Europe, Report Claims

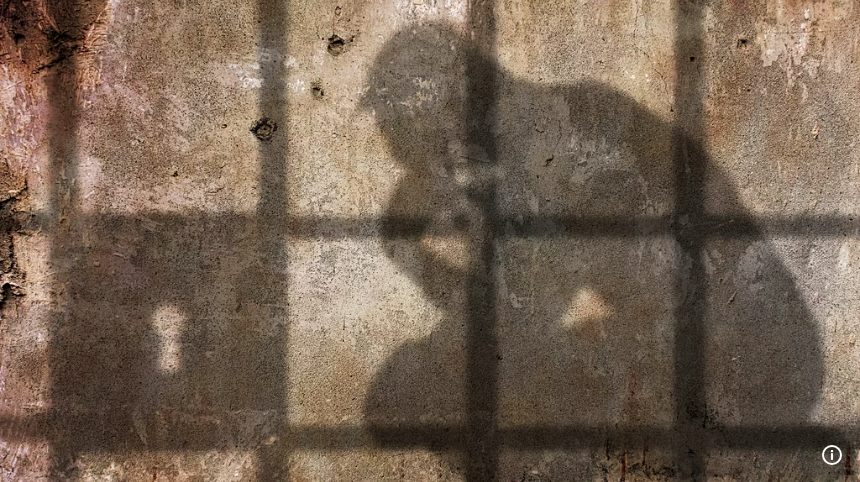

A new report has cast a harsh spotlight on Cuba’s prison system, alleging the existence of a vast network of forced labour camps that supply goods for export to European markets. According to the NGO Prisoners Defenders, tens of thousands of Cuban prisoners — including political detainees and common law offenders — are subjected to systemic forced labour under conditions described as “close to slavery.”

Published on Monday, September 15, the report accuses the Cuban government of orchestrating a state-run system that compels inmates to produce consumer goods such as charcoal and cigars for both domestic use and lucrative export. The findings, verified by the Institute for Crime and Justice Policy Research at Birkbeck University in London, paint a disturbing picture of exploitation, violence, and suffering hidden behind Cuba’s prison walls.

A Widespread Forced Labour System

According to Prisoners Defenders, Cuba currently holds around 90,000 prisoners, in addition to 37,458 individuals serving open prison sentences. Of these, an estimated 60,000 inmates are forced to work, often in gruelling and hazardous conditions. The report identifies 242 penitentiary facilities across the island — including prisons, so-called “correctional centres,” “labour camps,” and agricultural “farms” — where prisoners are deployed as unpaid or severely underpaid labourers.

Their tasks are varied and demanding: agricultural work in sugarcane and tobacco fields, charcoal production from marabu wood, construction projects, industrial tasks, garbage collection, and even cleaning duties in hospitals, police stations, and public streets. The report states that these forced labour programmes are deeply integrated into Cuba’s national economy.

Testimonies of Abuse and Exploitation

The report is built on official Cuban documents, field investigations, and dozens of testimonies from current and former prisoners. These personal accounts describe long hours, violent punishments, inadequate food and water, and no protective equipment or medical care.

“They force us to work from morning to night, under a scorching sun, without enough water or food. If you refuse, there’s immediate violence,” said Jorge, a former political prisoner quoted in the report. “Several of my colleagues collapsed from exhaustion, others were locked in solitary confinement for days, just for speaking out.”

Maria, a former common law prisoner, echoed this: “Working barefoot in the sugarcane fields, in the rain and heat, is like being a slave. No compensation, no respect. It’s a life of suffering where every day you wonder if you’ll make it.”

Many described deteriorating health, untreated injuries, and mental trauma as a result of forced labour. Among the most punishing jobs is charcoal production from marabu wood, one of Cuba’s primary agricultural exports. Prisoners tasked with making charcoal are forced to sleep in fields under makeshift shelters, without beds, clean water, or sanitation.

“To produce charcoal, we sleep in the fields, without a bed or a roof. We can only drink dirty water from a trough or from the cows on the neighboring farm,” said one inmate.

Charcoal and Cigars: A Profitable Prison Trade

The report claims that prison labour fuels some of Cuba’s top exports, particularly charcoal and Havana cigars. According to data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OCE) and the World Bank, charcoal made from prison labour was Cuba’s sixth most exported product in 2023, making the island the ninth-largest charcoal exporter in the world.

Main destinations include Spain, Portugal, Greece, Italy, and Turkey — with Cuban charcoal reportedly present across the European Union.

The same system allegedly extends into Cuba’s iconic tobacco and cigar industry, which is controlled by the state-owned Tabacuba company. The report cites the Quivican high-security prison, where about 40 inmates work in a cigar factory under civilian supervision, producing Habanos cigars primarily for export.

Prisoners there reportedly work up to 15 hours a day, six and a half days per week, with no breaks or snacks, earning barely €6 a month — compared to roughly €100 for civilian workers. Similar cigar factories reportedly exist in several Cuban prisons, contributing a significant share of the country’s export production.

The report estimates that the gross profit margins for the Cuban government on prison-made cigar and charcoal exports approach 100 percent, making it a highly lucrative enterprise.

Complicity and Silence Abroad

Prisoners Defenders warns that European distributors and importers are directly or indirectly benefiting from the labour of Cuban prison workers. Due to opaque supply chains and complex distribution networks, often involving local subsidiaries or intermediaries, tracing the origin of Cuban exports is extremely difficult. This lack of transparency shields foreign companies from accountability, allowing the trade in forced-labour goods to continue largely unchecked.

The NGO argues that international silence has enabled Cuba’s prison labour system to flourish, despite forced labour being banned by the UN Human Rights Council, the International Labour Organisation (ILO), and the European Convention on Human Rights.

Calls for International Action

Prisoners Defenders is now urging the international community to impose targeted embargoes on products made with forced labour, especially those exported to Europe. It also calls for the suspension of trade and cooperation agreements with Cuba until forced labour is abolished.

These recommendations come as the European Union prepares to implement new rules against forced-labour imports. In November 2024, the European Council adopted a regulation banning the sale, import, and export of goods made with forced labour, regardless of origin. While the regulation came into force in December 2024, EU member states have until December 2027 to implement it.

Human rights advocates argue that the Cuban case should become a litmus test for the EU’s commitment to these new rules.

A System Hidden in Plain Sight

The Prisoners Defenders report exposes what it describes as “a prison-based export economy built on forced labour,” one that not only violates international law but also sustains a profitable trade network reaching deep into European markets.

For now, Cuban prison-made charcoal and cigars continue to reach European consumers — often unlabelled and untraceable — while thousands of prisoners work in conditions described as inhuman, violent, and exploitative.

Unless international pressure intensifies, the NGO warns, Cuba’s prison labour system will continue to profit from suffering — hidden in plain sight.

Looking Forward

As the European Union prepares to roll out its ban on products made with forced labour, the coming years will be critical in determining whether meaningful change can reach Cuba’s prison system. Effective enforcement, transparent supply chains, and corporate accountability will be essential to ensure that goods produced under coercion no longer enter European markets.

For Cuba, international scrutiny could become a powerful catalyst for reform — if trade partners link cooperation and market access to tangible human rights improvements. And for global consumers, growing awareness offers the chance to demand ethical sourcing and push companies to verify the origins of the products they sell.

If the world chooses action over silence, the forced labour of thousands of Cuban prisoners could eventually give way to a system rooted in dignity, fairness, and human rights.

Conclusion

The Prisoners Defenders report has pulled back the curtain on a system of forced labour that appears to be deeply embedded within Cuba’s prison network — and quietly tied to global supply chains. With tens of thousands of inmates allegedly producing charcoal and cigars under conditions described as “close to slavery,” this is more than just a human rights issue; it is a trade and ethical crisis that directly implicates international markets, especially in Europe.

As long as Cuban prison-made goods continue to flow into foreign markets unchecked, the suffering of inmates will remain invisible to consumers and largely consequence-free for the companies that profit from it. The European Union’s upcoming forced-labour import ban could mark a turning point — but only if it is enforced rigorously and without exception.

Until meaningful international action is taken, Cuba’s prison labour system will persist as a grim reminder of how economic gain can thrive in the shadows of human suffering.

Meta Description:

A new report accuses Cuba of forcing tens of thousands of prisoners into labour to produce charcoal and cigars for export to Europe, under conditions described as modern-day slavery.

Prisoners in Cuba Forced Into Labour for Exports to Europe, Report Claims

A new report has cast a harsh spotlight on Cuba’s prison system, alleging the existence of a vast network of forced labour camps that supply goods for export to European markets. According to the NGO Prisoners Defenders, tens of thousands of Cuban prisoners — including political detainees and common law offenders — are subjected to systemic forced labour under conditions described as “close to slavery.”

Published on Monday, September 15, the report accuses the Cuban government of orchestrating a state-run system that compels inmates to produce consumer goods such as charcoal and cigars for both domestic use and lucrative export. The findings, verified by the Institute for Crime and Justice Policy Research at Birkbeck University in London, paint a disturbing picture of exploitation, violence, and suffering hidden behind Cuba’s prison walls.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

A Widespread Forced Labour System

According to Prisoners Defenders, Cuba currently holds around 90,000 prisoners, in addition to 37,458 individuals serving open prison sentences. Of these, an estimated 60,000 inmates are forced to work, often in gruelling and hazardous conditions. The report identifies 242 penitentiary facilities across the island — including prisons, so-called “correctional centres,” “labour camps,” and agricultural “farms” — where prisoners are deployed as unpaid or severely underpaid labourers.

Their tasks are varied and demanding: agricultural work in sugarcane and tobacco fields, charcoal production from marabu wood, construction projects, industrial tasks, garbage collection, and even cleaning duties in hospitals, police stations, and public streets. The report states that these forced labour programmes are deeply integrated into Cuba’s national economy.

Testimonies of Abuse and Exploitation

The report is built on official Cuban documents, field investigations, and dozens of testimonies from current and former prisoners. These personal accounts describe long hours, violent punishments, inadequate food and water, and no protective equipment or medical care.

“They force us to work from morning to night, under a scorching sun, without enough water or food. If you refuse, there’s immediate violence,” said Jorge, a former political prisoner quoted in the report. “Several of my colleagues collapsed from exhaustion, others were locked in solitary confinement for days, just for speaking out.”

Maria, a former common law prisoner, echoed this: “Working barefoot in the sugarcane fields, in the rain and heat, is like being a slave. No compensation, no respect. It’s a life of suffering where every day you wonder if you’ll make it.”

Many described deteriorating health, untreated injuries, and mental trauma as a result of forced labour. Among the most punishing jobs is charcoal production from marabu wood, one of Cuba’s primary agricultural exports. Prisoners tasked with making charcoal are forced to sleep in fields under makeshift shelters, without beds, clean water, or sanitation.

“To produce charcoal, we sleep in the fields, without a bed or a roof. We can only drink dirty water from a trough or from the cows on the neighboring farm,” said one inmate.

Charcoal and Cigars: A Profitable Prison Trade

The report claims that prison labour fuels some of Cuba’s top exports, particularly charcoal and Havana cigars. According to data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OCE) and the World Bank, charcoal made from prison labour was Cuba’s sixth most exported product in 2023, making the island the ninth-largest charcoal exporter in the world.

Main destinations include Spain, Portugal, Greece, Italy, and Turkey — with Cuban charcoal reportedly present across the European Union.

The same system allegedly extends into Cuba’s iconic tobacco and cigar industry, which is controlled by the state-owned Tabacuba company. The report cites the Quivican high-security prison, where about 40 inmates work in a cigar factory under civilian supervision, producing Habanos cigars primarily for export.

Prisoners there reportedly work up to 15 hours a day, six and a half days per week, with no breaks or snacks, earning barely €6 a month — compared to roughly €100 for civilian workers. Similar cigar factories reportedly exist in several Cuban prisons, contributing a significant share of the country’s export production.

The report estimates that the gross profit margins for the Cuban government on prison-made cigar and charcoal exports approach 100 percent, making it a highly lucrative enterprise.

Complicity and Silence Abroad

Prisoners Defenders warns that European distributors and importers are directly or indirectly benefiting from the labour of Cuban prison workers. Due to opaque supply chains and complex distribution networks, often involving local subsidiaries or intermediaries, tracing the origin of Cuban exports is extremely difficult. This lack of transparency shields foreign companies from accountability, allowing the trade in forced-labour goods to continue largely unchecked.

The NGO argues that international silence has enabled Cuba’s prison labour system to flourish, despite forced labour being banned by the UN Human Rights Council, the International Labour Organisation (ILO), and the European Convention on Human Rights.

Calls for International Action

Prisoners Defenders is now urging the international community to impose targeted embargoes on products made with forced labour, especially those exported to Europe. It also calls for the suspension of trade and cooperation agreements with Cuba until forced labour is abolished.

These recommendations come as the European Union prepares to implement new rules against forced-labour imports. In November 2024, the European Council adopted a regulation banning the sale, import, and export of goods made with forced labour, regardless of origin. While the regulation came into force in December 2024, EU member states have until December 2027 to implement it.

Human rights advocates argue that the Cuban case should become a litmus test for the EU’s commitment to these new rules.

A System Hidden in Plain Sight

The Prisoners Defenders report exposes what it describes as “a prison-based export economy built on forced labour,” one that not only violates international law but also sustains a profitable trade network reaching deep into European markets.

For now, Cuban prison-made charcoal and cigars continue to reach European consumers — often unlabelled and untraceable — while thousands of prisoners work in conditions described as inhuman, violent, and exploitative.

Unless international pressure intensifies, the NGO warns, Cuba’s prison labour system will continue to profit from suffering — hidden in plain sight.

Looking Forward

As the European Union prepares to roll out its ban on products made with forced labour, the coming years will be critical in determining whether meaningful change can reach Cuba’s prison system. Effective enforcement, transparent supply chains, and corporate accountability will be essential to ensure that goods produced under coercion no longer enter European markets.

For Cuba, international scrutiny could become a powerful catalyst for reform — if trade partners link cooperation and market access to tangible human rights improvements. And for global consumers, growing awareness offers the chance to demand ethical sourcing and push companies to verify the origins of the products they sell.

If the world chooses action over silence, the forced labour of thousands of Cuban prisoners could eventually give way to a system rooted in dignity, fairness, and human rights.

Conclusion

The Prisoners Defenders report has pulled back the curtain on a system of forced labour that appears to be deeply embedded within Cuba’s prison network — and quietly tied to global supply chains. With tens of thousands of inmates allegedly producing charcoal and cigars under conditions described as “close to slavery,” this is more than just a human rights issue; it is a trade and ethical crisis that directly implicates international markets, especially in Europe.

As long as Cuban prison-made goods continue to flow into foreign markets unchecked, the suffering of inmates will remain invisible to consumers and largely consequence-free for the companies that profit from it. The European Union’s upcoming forced-labour import ban could mark a turning point — but only if it is enforced rigorously and without exception.

Until meaningful international action is taken, Cuba’s prison labour system will persist as a grim reminder of how economic gain can thrive in the shadows of human suffering.

Meta Description:

A new report accuses Cuba of forcing tens of thousands of prisoners into labour to produce charcoal and cigars for export to Europe, under conditions described as modern-day slavery.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window) WhatsApp

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window) LinkedIn

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print