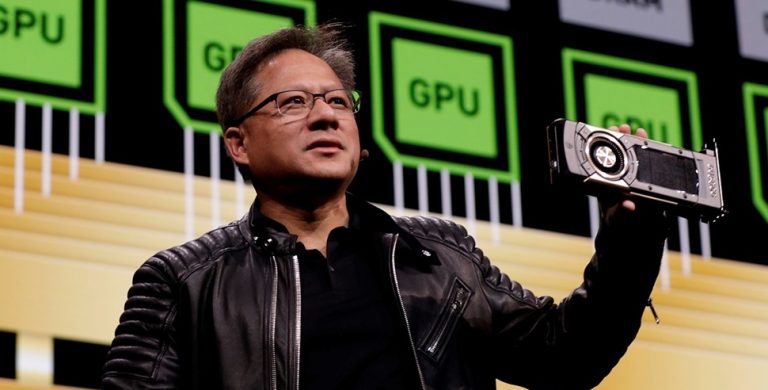

Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang is expected to travel to China in the coming days, ahead of the mid-February Lunar New Year, according to people familiar with the matter who spoke to CNBC.

Huang’s visit comes as Nvidia continues to grapple with tightening U.S. restrictions that have sharply narrowed the range of advanced artificial intelligence chips it can legally sell into China. Before those controls were imposed, China accounted for at least 20% of Nvidia’s data center revenue, making it one of the company’s most important overseas markets.

One of the sources said Huang is expected to attend an Nvidia company event in Beijing on Monday, part of what has become a regular Lunar New Year visit schedule for the chief executive. Huang, who was born in Taiwan and has longstanding ties to the region, has traveled to mainland China multiple times over the past year, including at least three visits in 2025 alone.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

Beyond ceremonial appearances, the trip carries strategic weight. Another person with direct knowledge of the plans said Huang is also expected to meet with potential Chinese customers and partners to discuss ongoing challenges in supplying Nvidia chips that comply with U.S. export rules. These discussions are likely to focus on logistics, availability, and the practical limits of demand for downgraded products designed specifically for the Chinese market.

While Nvidia has spent the past two years redesigning processors to comply with successive rounds of U.S. export controls, the company is discovering that formal approval does not necessarily translate into commercial certainty. Even when chips meet U.S. rules and clear licensing hurdles, broader security anxieties on both sides of the Pacific are increasingly shaping what can actually be sold, how it can be used, and who is willing to buy.

At the core of the impasse is Washington’s belief that advanced computing power has become inseparable from national security. U.S. officials view high-end AI chips as “force multipliers” that can accelerate military modernization, surveillance capabilities, cyber operations, and the development of autonomous weapons. That assessment hardened after China’s rapid advances in AI model training, drone swarms, and military-civil fusion programs, where commercial technologies are routinely adapted for defense use.

As a result, U.S. export controls on Nvidia are no longer narrowly targeted at the most powerful chips. They are designed to restrict aggregate computing capability, interconnect speeds, and scalability, making it harder for Chinese firms to cluster large numbers of compliant chips into systems capable of training frontier AI models. Each new rule has forced Nvidia to produce China-specific variants that are progressively less capable and, in many cases, less attractive to customers.

Beijing, for its part, sees the restrictions as a deliberate attempt to slow China’s technological rise and preserve U.S. dominance in AI. Chinese policymakers argue that Washington is weaponizing supply chains under the banner of security, even as U.S. companies continue to profit from global markets. This tension has fostered a climate of caution inside China, where regulators, state-linked firms, and research institutions are increasingly wary of over-reliance on U.S. suppliers, even when purchases are technically legal.

That dynamic helps explain why reports have surfaced suggesting that Nvidia’s H200 chips may be approved only for limited research use. From Beijing’s perspective, allowing broad deployment of U.S. AI hardware in commercial data centers risks future disruptions if relations deteriorate further. From Washington’s standpoint, even research use can raise concerns if it contributes to long-term capability building in sensitive sectors.

The situation leaves Nvidia navigating a narrow and shifting channel. On paper, the company can sell certain chips in China. In practice, those chips face layered scrutiny, informal guidance, and uncertainty over acceptable use cases. Chinese customers, especially large cloud providers and state-linked enterprises, must weigh whether investing in Nvidia hardware today could expose them to abrupt policy reversals tomorrow.

Security concerns also extend beyond China’s borders. U.S. officials worry that chips sold for civilian purposes could be diverted, resold, or integrated into systems supporting sanctioned entities. Enforcement has become more aggressive, with Washington pressing allies to tighten oversight and signaling that compliance failures could carry penalties. That has increased the compliance burden on Nvidia and its partners, complicating logistics even for approved products.

For Nvidia, China’s shrinking accessibility carries real financial implications. Before the restrictions, the country generated at least one-fifth of its data center revenue and played a key role in smoothing demand cycles. While U.S. hyperscalers and Middle Eastern customers have helped offset lost sales, China remains a market where demand for AI compute is structurally strong and politically constrained.

Huang’s repeated visits to China reflect this reality. They are not about reopening the floodgates, but about maintaining trust, clarifying boundaries, and keeping Nvidia relevant as Chinese firms accelerate domestic chip development. Beijing has poured billions into building alternatives, from state-backed foundries to AI accelerators designed by companies like Huawei. While these chips still trail Nvidia in performance and software maturity, the strategic push is unmistakable.

The geopolitical standoff has effectively turned Nvidia into a case study of how technology companies are being pulled into great-power competition. Approvals, licenses, and redesigned products now operate within a broader context of strategic suspicion that neither side appears willing to ease. Even as Nvidia complies with every written rule, unwritten concerns about security, leverage, and long-term dependence continue to limit what is possible.

In that sense, Huang’s China trip highlights a sobering shift for the global chip industry. The constraints facing Nvidia are no longer primarily technical or commercial. They are political, strategic, and enduring, shaped by a rivalry in which advanced semiconductors are viewed not just as products, but as instruments of power.