As Nvidia races to deploy its most powerful GPUs into Microsoft’s global data-center network, an internal note from early fall shows that the rollout hasn’t been entirely seamless.

In the email, an Nvidia Infrastructure Specialists (NVIS) team member questioned whether Microsoft’s cooling strategy at one facility was “wasteful,” underscoring the mounting resource pressures tied to the AI boom.

The observation came during the installation of GB200 Blackwell servers supporting OpenAI workloads — a reminder of how intertwined Nvidia, Microsoft, and OpenAI have become as the global AI arms race accelerates.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 20 (June 8 – Sept 5, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

Nvidia announced its Blackwell architecture in March 2024, touting it as roughly twice as powerful as the preceding Hopper generation. The GB200 series was the first wave of Blackwell systems shipped to hyperscalers, followed now by the newer GB300 generation already making its way into top-tier data centers.

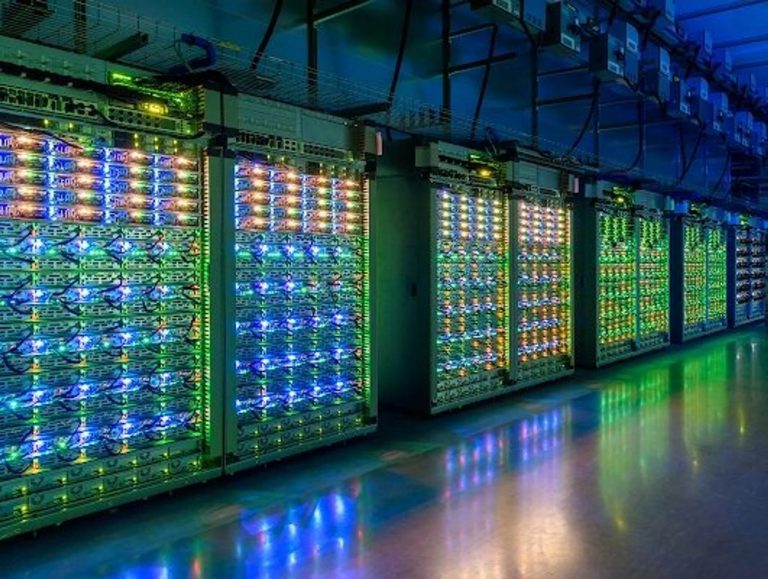

The email described the setup of two GB200 NVL72 racks — each holding 72 GPUs — installed for OpenAI via Microsoft’s cloud infrastructure. Given the extreme heat density created by these multi-GPU clusters, Nvidia’s systems rely on liquid cooling inside the racks. But a second facility-wide cooling layer is still required to expel the heat, and this is where the Nvidia staffer raised concerns.

Microsoft’s approach “seems wasteful due to the size and lack of facility water use,” the Nvidia employee wrote, though the note acknowledged that the design offered flexibility and fault tolerance.

Shaolei Ren, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of California who studies data-center resource use, offered context consistent with the internal critique. He said the Nvidia staffer was likely referring to the building-level cooling stage. In some facilities, Microsoft uses an air-based system at this second stage rather than a water-based one.

“This type of cooling system tends to be using more energy,” Ren said, “but it doesn’t use water.”

Ren added that operators face a “trade-off” between water use and energy consumption. Air cooling consumes more power, but it avoids the public pushback that often comes with heavy water usage — now one of the most sensitive environmental issues facing hyperscalers and AI developers around the world.

Microsoft confirmed that the installation used a closed-loop liquid cooling heat exchanger inside an air-cooled facility.

“Microsoft’s liquid cooling heat exchanger unit is a closed-loop system that we deploy in existing air-cooled data centers to enhance cooling capacity,” a spokesperson told Business Insider.

The company said the hybrid approach allows it to scale AI infrastructure using its existing footprint while maintaining efficient heat dissipation and “optimizing power delivery to meet the demands of AI and hyperscale systems.”

The debate around cooling is no longer technical background noise — it is central to the politics and environmental footprint of AI expansion. In regions from Europe to the American Southwest, community groups and local governments have pushed back against hyperscale data centers over water use, energy intensity, and strain on local grids. Ren noted that companies weigh energy costs, water costs, and “publicity cost” in deciding which cooling strategy to adopt.

Microsoft insists it remains on track to meet its self-imposed 2030 goals to become “carbon negative, water positive, and zero waste.” It has also announced a “zero-water” cooling design for future facilities, along with advances in on-chip cooling intended to reduce thermal load at the processor level.

The Nvidia memo, while flagging cooling as an area of inefficiency, also described common early-deployment challenges. Blackwell’s first large-scale rollouts require close coordination between Nvidia and hyperscaler staff, and the email said on-site support was critical. Validation documentation needed extensive rewriting, and handover processes between Microsoft and Nvidia “required a lot more solidification.”

Still, the note suggested that Nvidia’s production hardware quality has improved significantly from the early qualification samples customers received before the formal launch. Both NVL72 racks deployed at the facility achieved a 100% pass rate on compute performance tests.

Nvidia, in its public response, said Blackwell systems “deliver exceptional performance, reliability, and energy efficiency” and that companies such as Microsoft have already deployed “hundreds of thousands” of GB200 and GB300 NVL72 systems.

The episode offers a glimpse into the intense, resource-hungry infrastructure race beneath today’s AI boom. Nvidia is under pressure to deliver chips fast enough. Microsoft is under pressure to build cooling and power capacity fast enough. And the entire industry is under pressure to justify its environmental footprint as AI workloads grow at a pace no one predicted even three years ago.

The friction is almost inevitable. Blackwell is far more powerful — and far more thermally demanding — than anything that came before it. As deployments scale into the hundreds of thousands, cooling will remain one of the most contested, expensive, and politically sensitive aspects of the AI infrastructure buildout.

And if the industry’s trajectory is any guide, the next-generation chips coming after Blackwell will only intensify that battle.