Over the past nine years, education workers in Nigeria have been the main targets of the “No Work, No Pay” policy as both federal and state governments use it to curb frequent strikes and enforce discipline across the public sector. A review of documented applications between 2016 and 2025 by our analyst shows that nearly four out of every ten times the policy was applied, it affected teachers, lecturers, and other education sector staff.

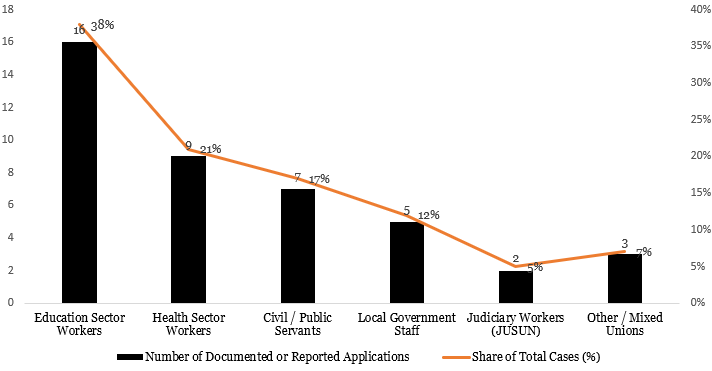

Our analysis reveals that governments at both levels invoked the controversial policy 42 times within the period. Education workers accounted for 16 of those cases, representing about 38 percent of total applications. The health sector followed with nine instances, or 21 percent, while civil servants faced the policy seven times. Local government workers were targeted in five cases, and judiciary workers twice.

At the federal level, the policy became most visible in 2022 when the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) embarked on an eight-month strike. The federal government insisted on enforcing “No Work, No Pay,” a stance that later extended to polytechnic lecturers and college workers in subsequent years. The Federal Ministry of Labour argued that the measure was a legal deterrent against indefinite strikes that disrupt essential services. However, unions maintained that it was punitive and ignored the root causes of industrial actions such as poor funding and unmet agreements.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

The Federal Capital Territory, though under federal administration, also recorded its own cases. Between 2022 and 2024, education and area council workers faced salary suspensions after prolonged strikes. The FCT Administration justified its actions as necessary to restore work discipline in the public education system, which has struggled with frequent disruptions.

Across the states, the picture is consistent. In Oyo, the policy was applied to teachers and civil servants during the 2018 strikes, while Kaduna used it in 2021 against teachers and state workers after a confrontation between the government and the Nigeria Labour Congress. Lagos and Kano enforced it against teachers between 2022 and 2025, while Ekiti and Anambra applied it to health workers during salary disputes. Rivers, Cross River, and Abia had isolated cases involving local government and judiciary staff.

Although 14 other states had occasional mentions of the policy, particularly during teachers’ or nurses’ strikes, most did not sustain implementation due to political pressures or negotiations that followed. The data shows that while state governments invoke the policy rhetorically, only a few follow through with full enforcement.

Exhibit 1: Aggregate Frequency by Worker Type (National Overview, 2016–2025)

The frequent application in the education sector reflects the ongoing tensions between government fiscal management and public sector unionism. Teachers and lecturers, who form some of the largest organised unions in Nigeria, often strike to demand wage reviews, improved funding, or better working conditions. For the government, the “No Work, No Pay” rule has become a tool to manage financial exposure during protracted industrial actions.

In practice, the policy’s implementation has been uneven. While federal authorities enforced it rigidly against ASUU in 2022, other unions in health and local government sectors later received partial payments after negotiations. In some states, the policy was reversed following public outcry, especially when it affected essential service providers like nurses and teachers.

The frequency data also suggests that enforcement is more common in politically stable or reform-driven states such as Lagos, Kaduna, and Oyo. These states tend to emphasize administrative discipline and budget accountability. In contrast, states with weaker fiscal positions often delay or suspend salary payments regardless of strike actions, making the “No Work, No Pay” rule less effective or even redundant.

Experts note that the selective application of the policy undermines its credibility. Labour analysts argue that its effectiveness depends on government transparency and consistency. They point out that in many cases, strikes arise from unpaid wages or unimplemented agreements, which makes punishing workers for not working during such periods ethically questionable.

Despite the controversies, both federal and state governments appear committed to keeping the policy in their industrial relations toolkit. In 2025, some states, including Lagos and the FCT, reaffirmed their readiness to invoke it against any worker unions that disrupt public services.

The data underscores a broader issue in Nigeria’s labour relations. While “No Work, No Pay” seeks to discourage strikes, it has also deepened mistrust between workers and the government. Education workers remain the most targeted, yet they continue to play a central role in demanding reforms and accountability. The trend suggests that unless structural challenges in public funding and wage management are addressed, the policy will remain a recurring feature of Nigeria’s industrial landscape