We’ve all been there: you’re scrolling through Instagram and stumble upon a video that stops you in your tracks. It might be a breathtaking travel clip, a hilarious meme, a crucial tutorial, or a precious memory shared by a friend. Your first instinct? Download Instagram video content to save it for later. Yet, as you probably know, Instagram doesn’t make this straightforward. Unlike some other platforms, its native app only offers a “Save” feature, which bookmarks the video within Instagram rather than saving it to your device. This guide will walk you through the simplest, safest methods to download videos from Instagram, focusing on one standout tool that makes the process effortless.

The Challenge of Downloading Instagram Videos

Instagram, at its core, is a social sharing platform designed to keep content circulating within its ecosystem. To protect creators’ rights and maintain user engagement, direct download options for videos and photos are not provided. This creates a common dilemma for users who wish to keep content for offline viewing, inspiration, or personal collection without relying on an internet connection or the risk of the original post being deleted.

Many users resort to taking screenshots or screen recordings, but these methods have significant drawbacks in quality and convenience. Others search the web for “how to download Instagram videos” and are met with a sea of websites and applications, varying widely in safety, reliability, and ease of use. Navigating this landscape can be time-consuming and sometimes risky, with concerns about malware, intrusive ads, or violating terms of service.

How to Save Instagram Videos Without Any Tools

Before exploring dedicated tools, it’s worth mentioning the manual workarounds.

- Using Screen Recording (Lower Quality, Cumbersome)

Most smartphones and computers have built-in screen recording functions. For a quick save, you can play the Instagram video in full-screen and activate the recorder. However, this method has notable flaws: - Lower Quality:The recording captures exactly what’s on your screen, which may not be the original resolution. You’ll also record UI elements, your own taps, and notifications.

- Cumbersome Editing:You’re left with a video file that includes everything before and after the target clip, requiring you to trim it manually.

- Audio Issues:Sound can sometimes be poorly captured or missing entirely due to app restrictions.

While this method is free and requires no extra apps, it’s inefficient for downloading multiple videos and rarely provides a clean, high-quality result. For a true download video from Instagram experience, you need a better solution.

The Easiest Way to Download Instagram Videos: EasyDown

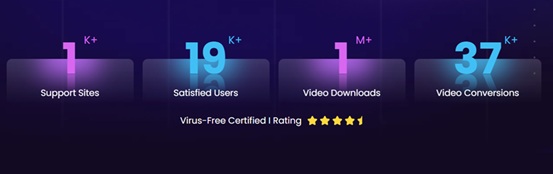

For users who frequently want to save high-quality Instagram content, a dedicated downloader is the answer. Among the many options available, EasyDown Video Downloader stands out for its simplicity, reliability, and excellent results.

What is EasyDown?

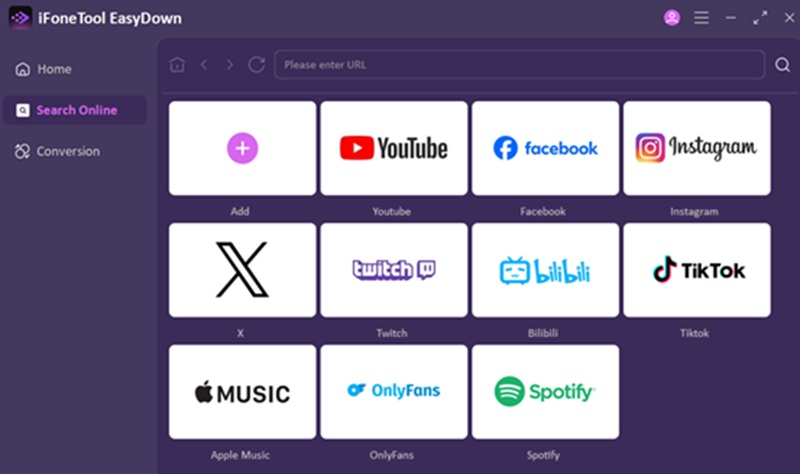

EasyDown is a versatile, multi-platform solution designed specifically for downloading videos and music from over 1,000 platforms, including giants like Instagram, YouTube, TikTok, and Spotify. From a quick Instagram Reel to a full YouTube playlist, it handles it all in one clean interface. For anyone figuring out how to download videos from Instagram and other sites, EasyDown presents a unified answer.

Key Features

- Universal Platform Support: While our goal is to download video from Instagram, EasyDown’s capability extends far beyond. It’s a single tool for all your downloading needs, eliminating the clutter of multiple apps.

- Batch Downloading Power: Imagine finding an Instagram user or a themed playlist whose content you adore. Instead of saving each post individually, EasyDown’s batch feature lets you download entire collections with one click, saving immense time.

- Preserve Original Quality: There’s no point in saving a stunning 4K travel video if it loses its sharpness. EasyDown fetches the highest available resolution—up to 4K for videos—directly from the source, so what you save is what you saw.

- Streamlined, Ad-Free Experience: The process is refreshingly straightforward. You’ll encounter no distracting pop-up ads or confusing navigation. It’s a clean space where you paste a link and get your file.

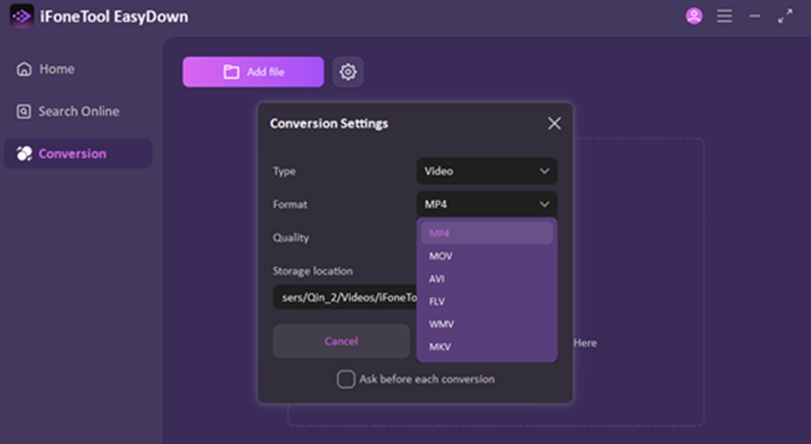

- Smart Format Conversion: Need that Instagram video in MP4 for editing or MP3 for just the audio? With one click, EasyDown can convert your download into the optimal format for your device or project, ensuring hassle-free compatibility. It also allows you to download YouTube playlist to MP3.

Step-by-Step Guide to Using EasyDown

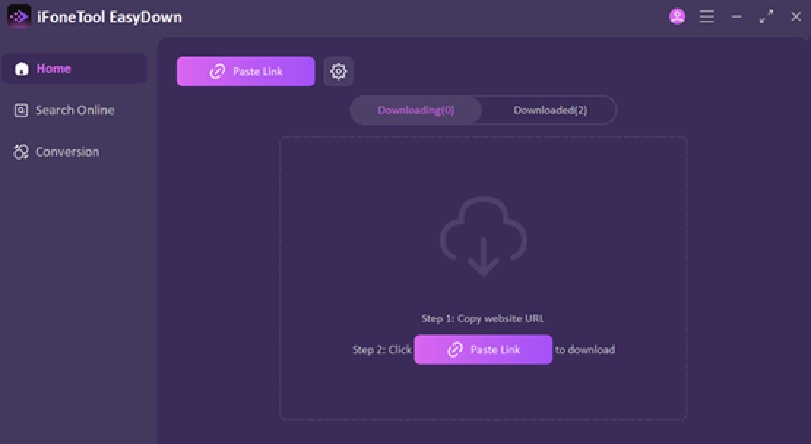

Using EasyDown is remarkably simple. Here’s how you can download Instagram video content in four easy steps:

- Copy Your Instagram Link: Within the Instagram app, tap the three dots (…) above the post you wish to save and select “Copy link.”

- Paste into EasyDown: Open the EasyDown application. You’ll find a prominent URL field—paste your copied link there.

- Select Your Preferences: EasyDown will instantly analyze the link. It will present you with available download options. Here, you can select your desired video quality and output format.

- Initiate the Download: After making your selection, click the “Apply” EasyDown will process the file and save it directly to your designated download folder.

Why EasyDown is the Best Choice for Downloading Instagram Videos

With numerous downloaders available, why choose EasyDown? It excels in the areas that matter most to everyday users.

First, its versatility is a game-changer. In a digital world where our favorite content is scattered across Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and more, EasyDown consolidates the need for multiple tools into one powerful application. Learning how to download videos from Instagram with EasyDown means you’re also learning how to save content from nearly any other platform, making it an invaluable addition to your digital toolkit.

Second, it never asks you to compromise on quality. Many free downloaders degrade video resolution or audio bitrate. EasyDown operates on the principle that you deserve the original file. Whether it’s a high-frame-rate Reel or a detailed IGTV video, you get a pristine copy, allowing you to truly preserve the content you love.

Finally, the experience is crafted for simplicity and respect. The ad-free, intuitive interface removes all friction from the process. There are no hidden steps, deceptive buttons, or unnecessary bloat. It performs its core function—allowing you to download video from Instagram and other sites—with impressive efficiency and respect for your time and attention. For the regular user who values quality, ease, and broad utility, EasyDown presents an unmatched solution.

Legal Considerations When Downloading Instagram Videos

It is crucial to address the ethical and legal side of downloading content. While tools like EasyDown provide the ability to download, the responsibility lies with you, the user.

- Respect Copyright:Most content on Instagram is protected by copyright. Always assume the video belongs to the person who posted it.

- Intended Use is Key:Downloading videos for personal, offline viewing is generally considered fair use in many contexts. This means you can save a tutorial to watch later or a friend’s post to keep as a memory.

- What to Avoid:Never use downloaded videos for commercial purposes, re-upload them to other platforms as your own, redistribute them, or use them in a way that could harm the creator or infringe on their rights.

- Seek Permission When in Doubt:If you intend to use the video beyond personal viewing, the safest course is to contact the content creator directly and ask for permission.

Instagram’s Terms of Service prohibit the use of automated means to collect content without permission. Using a downloader technically breaches these terms, so it’s essential to use such tools judiciously and respectfully.

Conclusion

The desire to download video from Instagram is a common one, driven by the wish to preserve inspiring, educational, or memorable content. While manual methods like screen recording exist, they are often inadequate. For a fast, high-quality, and hassle-free experience, a dedicated web tool like EasyDown is the optimal solution. It answers the question of how to download videos from Instagram with a process that is quick, easy, and reliable.

Remember, with the power to download comes the responsibility to do so ethically. Use these tools to enhance your personal media library, not to undermine the hard work of creators. Save the videos you love, respect the people who made them, and enjoy your favorite Instagram moments anytime, anywhere.