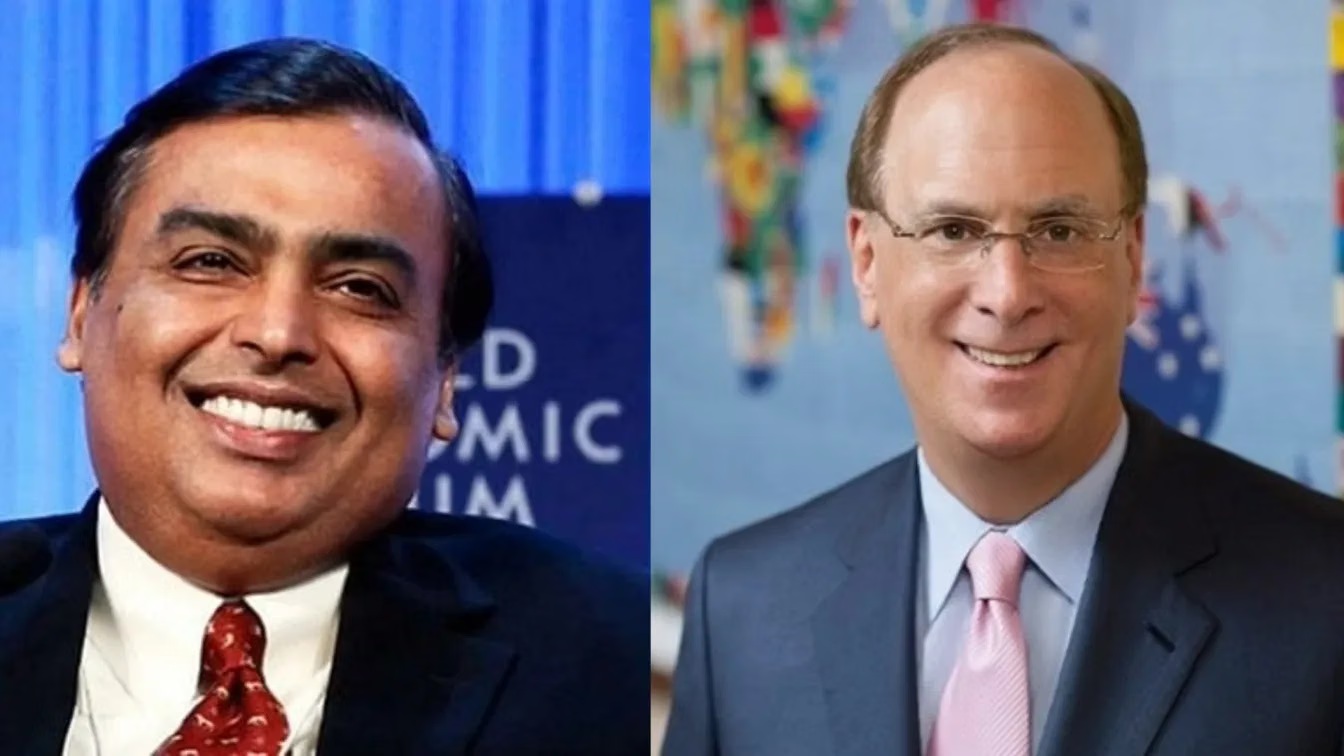

BlackRock CEO Larry Fink and Reliance Industries Chairman Mukesh Ambani are pushing a familiar but increasingly consequential argument in India’s financial discourse, that the country’s vast household savings would be better deployed in equity markets than locked away in gold.

Their intervention comes at a moment when market signals are mixed, investor sentiment is uneven, and the tension between tradition and financial modernization is once again in focus.

The remarks were made during a public fireside chat at a time when Indian equities have struggled to gain traction this year. The benchmark Nifty 50 is down nearly 2% so far, while gold has attracted attention amid heightened volatility driven by global interest rate uncertainty, geopolitical risks, and central bank buying. Against that backdrop, Ambani described domestic savings tied up in gold and silver as largely “unproductive,” arguing that money invested in equities compounds over time in ways physical assets do not.

The subtext of the conversation was not subtle. India’s household balance sheet remains heavily skewed toward physical assets, even as its capital markets mature and broaden. Gold, in particular, plays an outsized role, serving as a store of value, a hedge against inflation, and a cultural anchor that cuts across income levels. Yet for policymakers, economists, and global asset managers, that preference represents idle capital in an economy still hungry for long-term investment.

Fink’s message leaned heavily on the long view. He said the next 20 to 25 years would be an “era of India,” urging citizens to invest in their own country’s growth through capital markets rather than relying on traditional savings instruments. His confidence is rooted in macroeconomic forecasts that continue to set India apart from most major economies. The International Monetary Fund expects India to grow by 6.4% in 2026, making it the fastest-growing large economy globally. By contrast, global growth is projected at 3.3%, with economies such as Germany, the United Kingdom, and Japan expected to expand only marginally.

That growth gap underpins the broader equity argument. In Fink’s telling, those who participate in an economy’s expansion through markets tend to accumulate far more wealth than those who keep their savings idle or confined to low-yield assets. Drawing on BlackRock’s experience in the United States, he said Americans who invested in the country’s growth were far “better off than those who just kept all their money in a bank account.”

In a separate interview with The Economic Times, he went further, predicting that Indian equities could “double and triple and quadruple” over the next two decades, while adding bluntly that he does not see gold delivering comparable returns.

Ambani’s intervention carried its own weight. As chairman of India’s largest conglomerate, his remarks reflected a corporate perspective that sees deeper domestic capital markets as essential to sustaining long-term growth. For companies like Reliance, a broader and more active retail investor base can lower funding costs, reduce dependence on foreign capital, and stabilize markets during periods of global risk aversion.

There is also a clear business dimension to the push. Reliance and BlackRock partnered last year to form Jio BlackRock Asset Management, marking the U.S. firm’s re-entry into India’s mutual fund industry. The joint venture launched its first equity fund in August and had assets under management of 31.98 billion rupees, or about $353 million, across its equity funds by the end of December.

While small relative to the size of India’s mutual fund industry, the figure signals the ambitions of global asset managers who see household financialisation as one of the country’s biggest untapped opportunities.

India’s savings landscape is already changing, albeit gradually. Mutual funds have become more popular as digital platforms simplify access, and systematic investment plans allow households to invest small sums at regular intervals. Data from the Association of Mutual Funds in India shows that investments through SIPs tripled to 2.89 trillion rupees, or about $31.9 billion, in the 2025 financial year compared with 2021. That steady flow of domestic money has helped cushion Indian markets even as foreign investors have been net sellers of equities for more than a year.

Still, physical assets continue to dominate. According to Bain & Company, Indians allocated nearly 59% of their assets to gold and real estate in the 2025 financial year, down from 66% a decade earlier but still a clear majority. Bain estimates that retail investor-driven assets in the mutual fund industry could rise to 300 trillion rupees, or about $3.3 trillion, by 2035, from 45 trillion rupees in fiscal year 2025. The scale of that potential shift highlights why figures like Fink and Ambani are pressing the issue now.

Market performance adds complexity to the narrative. Over the past year, the MSCI India Index delivered a dollar return of just 2.61%, sharply lagging the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, which returned 43.67%. That underperformance has tested investor patience and reinforced the appeal of gold during periods of uncertainty.

Over a five-year horizon, however, India has told a different story, with its equity index delivering nearly twice the returns of the broader emerging markets benchmark. Supporters of equities argue that this contrast illustrates the danger of focusing too narrowly on short-term cycles.

Beyond returns, the debate has broader economic implications. Redirecting household savings from gold to equities could reduce India’s reliance on gold imports, which have long weighed on the current account. It could also provide domestic companies with a more stable source of long-term capital, strengthening the financial system and supporting infrastructure and industrial investment.

Yet cultural inertia remains a powerful force. Gold’s role in Indian households is not purely financial; it is bound up with social security, weddings, inheritance, and trust in tangible assets. Shifting that mindset will likely require more than bullish forecasts from global financiers and industrialists.

Consistent market returns, stronger investor protection, and sustained financial literacy efforts will be critical in convincing households that equities can serve as a reliable engine of wealth.