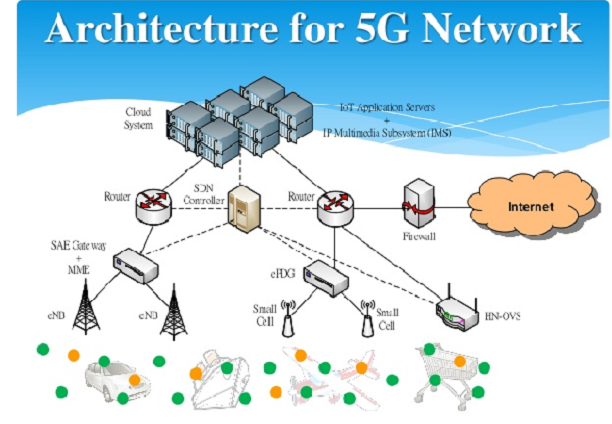

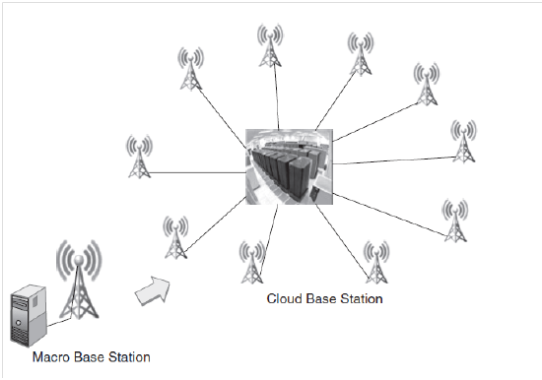

The 5G network has been designed based on a new architecture which features a new air interface, called the 5G NR, which will be briefly introduced in this section. The 5G NR also presents two system architectures for migrating from 4G to 5G networks, which will be discussed in this section.

4.1 5G New Radio (NR)

The 5G NR represents a new air interface and radio access network (RAN) developed to meet the varied requirements of the 5G use cases such as high bandwidth, low latency, energy efficiency etc.

Some of the key features of the 5G NR include

- Radio Spectrum: As discussed and depicted in chapter 2, 5G NR would work across a wide range of frequency bands.

- Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing (OFDM): 5G NR will use OFDM as its underlying modulation scheme [32].

- Beam-forming: As highlighted in chapter 2, 5G NR will support the use of beamforming to achieve higher throughput.

4.1.1 Carrier Aggregation

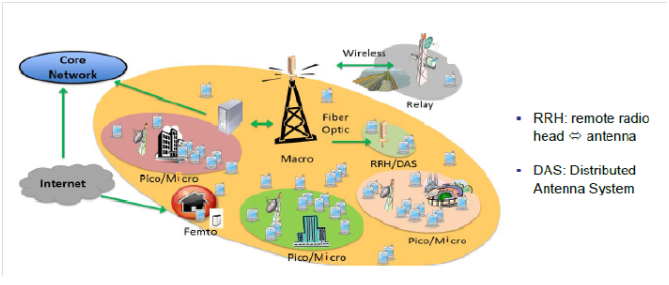

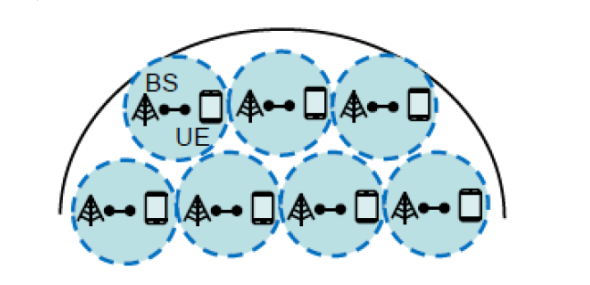

Carrier Aggregation is a technique applied at the physical layer (5G NR). 5G clearly requires the use of different frequencies in different bands, as mentioned in Chapter 2. Carrier Aggregation thus allows for the combination of carriers either within the same or different bands.

For example, it is common for the primary control channel to be anchored on the macro cell using a lower frequency for reliability and coverage whereas the data channel can operate from the small cell using a higher frequency to provide for higher data rate and network capacity [12]. The separation of the data and control channels would be discussed further in Chapter 5.

In the next sections, the reader will be introduced to the two architectural routes for migrating from 4G to 5G.

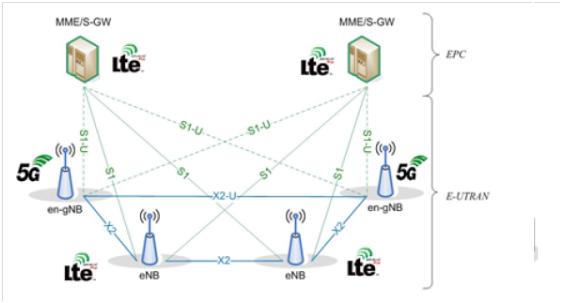

4.2 Non Stand Alone Architecture

In a non-stand alone architecture, the 5G NR is used in conjunction with the 4G networks. This allows 5G based radio technology (5G NR) to be used with the existing 4G networks and represents a faster route towards commercial deployment of 5G networks.

The Non stand alone architecture serves as a temporary step towards full 5G deployment.

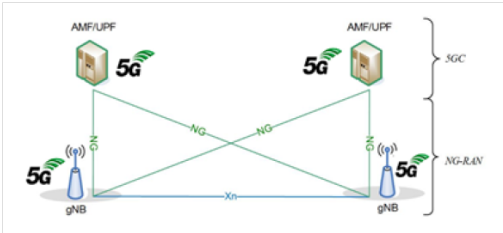

4.3 Stand Alone Architecture

This represents the full 5G deployment and is obviously a slower route towards commercial deployment. Here, the 5G NR is connected directly to the 5G Core (5GC) network. In essence, the 5G system is made of the UE, 5G NR and 5GC.

As depicted above in the figure, the NR (depicted as gNB) connects to each other via the Xn interface whereas the New Radio -Radio Access Network (NG-RAN) connects to the 5GC via the NG interface.

4.4 Summary

In this section, we discussed two main routes towards the commercial deployment of 5G networks. One represents a faster route and involves the use of the 5G NR on a 4G network whereas the other represents a slower route and involves the full utilization of the 5G NR on a 5GC network.