A lot of fuss and fury followed the announcement by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences that “Lion Heart”, a film of Nigerian origin, submitted for the Oscar Award, has been disqualified for having too much dialogue in English.

Lion Heart is the first Nigerian film ever to be submitted for the Oscars, and there’s high hope it will make up for the years that Nigeria was not represented.

Directed by Genevieve Nnaji, who also starred in the movie alongside Pete Edochie, Nkem Owoh, among others, Lion Heart which was co-produced by Chinny Onwugbenu, earned strong reviews when it was premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, and was acquired by Netflix, where it is currently streaming.

What went wrong?

Earlier this year, the Oscar Academy changed the name of the category that Lion Heart was submitted in, from best foreign language film to best international feature film. And the rule is that films submitted in this category must have a predominantly non-English dialogue track. Lion Heart was a 95-minute-film, and only about 11 minutes contains Igbo language, which runs afoul of the rule because it is English dominated.

But Lion Heart isn’t the first film to be disqualified for the same reason. In 2015, Afghan film, Utopia was disqualified for having too much English, and so was the 2007 Israeli movie, The Band’s Visit.

Why so much fuss about the disqualification?

Lion Heart was one of the 10 African films officially submitted for the Oscar Awards this year, and it’s a record for the African continent. With this disqualification, the total number of nominees for the award has been dropped from 93 to 92, reducing the African numbers to nine.

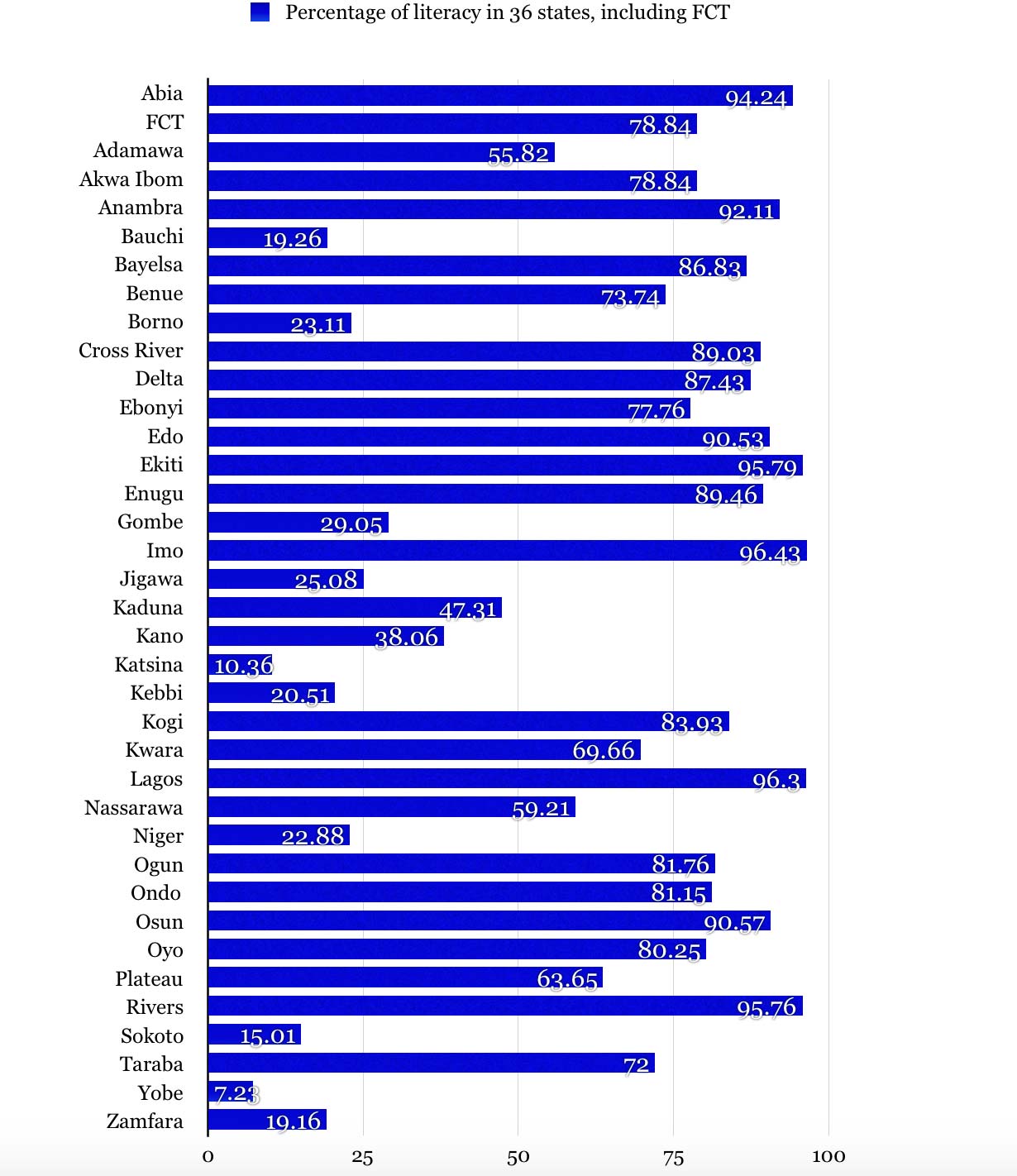

Moreover, the disqualification was based on foreign language. The official language of Nigeria is English and it is predominantly spoken to bridge the barrier created by the multilingual ethnicities in the country. There are over 256 languages spoken in Nigeria, making it impossible to choose just one to represent the country. Not even from the predominant three – Hausa, Igbo and Yoruba. So English became the language you can speak in any part of Nigeria and be understood apart from the invented pidgin. Apart from the fact that it was introduced by the colonial masters as a way of uniting their colony and communicating with the people.

When compared to Utopia and The Band’s Visit, the Afghan official languages are Pashto and Dari while the Israeli official language is Hebrew. A clear contrast in the case of Lion Heart, and a reason many have been angered by the Academy’s decision to disqualify the film.

The decision has for this reason, drawn a lot of backlash from people around the world. Hollywood producer, Ava DuVernay took to her Twitter handle to swipe at the Academy for the decision. She tweeted: “To the Academy, you disqualified Nigeria’s first-ever submission for Best International Feature because it’s in English. But English is the official language of Nigeria. Are you barring this country from ever competing for an Oscar in its official language”?

In response to this tweet, Genevieve tweeted: “Thank you so much Ava. I am the director of Lion Heart. This movie represents the way we speak as Nigerians. This includes English which acts as a bridge between the 500+ languages spoken in our country, thereby making us one Nigeria.

“It’s no different to how French connects communities in former French colonies. We did not choose who colonized us. As ever, this film and many like it, is proudly Nigerian.”

Others too weighed into the controversy. Franklin Leonard, founder of the popular series, Black List, tweeted: “Colonialism really is a bitch.”

Another actor, Aida Rodriguez, sent a tweet in solidarity to Lion Heart saying: “Oh, the penalties of colonization.”

Ivie Ani, a journalist and music editor couldn’t hide her disappointment either, she tweeted:

“More than 500 indigenous languages are spoken in Nigeria, yet Nigeria’s official language is English. A Nigerian film in English can’t win the Oscars’ foreign category because it’s not foreign enough. Colonizers love to punish the colonized for being colonized.”

However, the decision of the Academy to disqualify Lion Heart shows one thing; they know little or nothing about Nigeria or how we live. As Genevieve said, “Lion Heart represents how we speak in Nigeria,” 70 to 80 percent of English and about 20 percent of our indigenous language.

The ongoing push by the Academy to accommodate more members from overseas may have eligibility hindrances, stemming from the International category rules that seem arbitrary and perplexing due to lack of understanding of the culture of people and places where the film is coming from.

The United States doesn’t have an official language, and that would have made it difficult for those who make the rules to understand the role English plays in multilingual societies where it is the official language.

Meanwhile, Lion Heart has not been disqualified in other categories, and the film still has a chance of winning an Oscar.