Note: This is a remix of The Path To Disaster: A Startup Is Not A Small Version of A Big Company, a blog post I wrote for publication at Tekedia on August 20, 2012. This remix is based on my experience meeting early stage startup founders in NYC since then.

Each time I hold office hours in New York City, I encounter at least one individual who comes by to ask me a version of the question: “Where do I start?”

Some are first-time founders just getting started, others are in the midst of making a transition from being employed at a company to striking out to start something on their own, or with one or two other people. In every case so far I would not characterize any of the people who have asked me this question as completely clueless, in the sense that they have a network that includes many early stage investors – angels, and venture capitalists, and they know other people who are startup founders, they read numerous blogs etc.. They have asked this question of others . . . . . and yet when they encounter me at office hours they say they still feel confused.

I always promise that they will leave with a framework that they will always be able to use as a guide. This post outlines the conversation we have.1

I like to start with a few definitions, because that ensures that we are on the same page and thinking about things in the same way.

Definition #1: What is a Project? A Project is an undertaking by an individual or a group of individuals in order to accomplish a specific goal.

Definition #2: What is a Startup? A startup is a temporary organization built to search for the solution to a problem, and in the process to find a repeatable, scalable and profitable business model that is designed for incredibly fast growth. The defining characteristic of a startup is that of experimentation – in order to have a chance of survival every startup has to be good at performing the experiments that are necessary for the discovery of a successful business model.2

Definition #3: What is a Company? A company is a business organization that has been built for the specific purpose of scaling a repeatable, and scalable business model.

Given those definitions, let’s revisit the question I get asked by first-time founders; “Where do I start?”

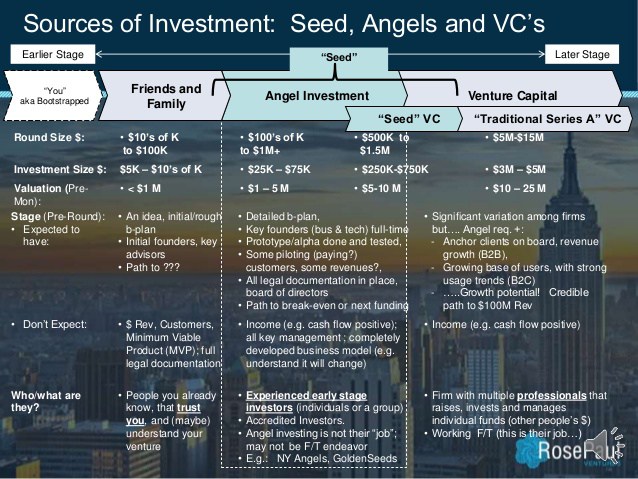

Sources of Investment: Seed, Angels and VCs by Thomas Wisniewski, via SlideShare

Inflection Point 1: Idea -> Project

Initially, an individual, perhaps two or three individuals who know one another discuss an idea and feel that they may be onto something that could become big. At that point they have a project, and their goal is to determine if their idea is a big enough one to merit devoting more resources to transforming into a physical thing. This could happen while they are still in school, or perhaps while they are employed. So work on the project occurs at night, during weekends, and in whatever free time they can find. Importantly, the project is not yet a top priority. During this stage the founder or founders will be bootstrapping, spending their personal capital in order to conduct whatever research they feel they need to perform in order to make some progress.

If they eventually conclude that the idea has enough merit to become a business one day, and they would like to pursue building that business, then they begin the transition from working on a project to forming a startup.3

Inflection Point 2: Project -> Startup

Once they make the choice to become a startup, it is most likely that the team will need to devote additional resources to their endeavor. For example; the team needs to start building a product – a minimum viable product, someone has to start thinking about how to win early customers/users, and more time has to be devoted to sorting out a number of other issues like how everything that needs to get done at this stage will be paid for.

Friends & Family

If everything is going well so far, the founders might decide that they need some external capital. At this stage the easiest source of capital is the founders’ friends and family and the amount of capital raised will generally be less than $1,000,000. This round of capital should be devoted to building a minimum viable product (MVP) and confirming the hypotheses that the founders started to examine when this undertaking was “merely” a project.

The key point here is that people in this group know the founders personally and are making an investment largely on the basis of their trust and belief in the founders. Often the investors in this category do not understand much about what the founders are building if the product involves a technological innovation. However, they likely believe “Brit is smart and hardworking. We know she will do great. We want to support her build her dream.” So while a financial return would be nice, it is not the primary motivation. Nonetheless, I advise founders to make it a habit to pitch the idea formally even to this group of potential investors because it is worth the effort to start learning to pitch other people even at that early stage.

This round will probably be a convertible debt round, with terms driven by the founders.

The minimum viable product is the smallest, least expensive product that can be built in order to test the most important hypothesis on which the startup’s business model will depend.

– Paraphrasing Teresa Torres

Angel Investors

If things go well enough, the founders decide that they need to raise even more capital, more than they can expect to raise from their immediate social circles. There are still important questions that remain to be answered. The business model has not yet been discovered. Although early customers/users have been identified there is not yet any meaningful revenue traction. It may be a few more months before the product is mature enough to generate meaningful revenues although potential customers/users are testing the product and so far the key performance indicators (KPIs) look promising. There is still substantial work to be done on product features, but there is enough for some early customers to consider paying for.

An angel round will generally be about $1,000,000 or slightly more, but generally less than $2,000,000 or so. With each angel investor typically investing an amount between $25,000 – $100,000 or so.

This round will probably be a convertible debt round, whose terms will be driven by a lead angel who will do some work on behalf of the group. If the round is raised from an organized angel investor network, then the process might unfold according to the framework within which the group operates.

Angels will generally have a much more sophisticated understanding of the product and the market than individuals who invested in the Friends & Family round.

Seed Stage Venture Capitalists

Two important differences between Angel Investors and Seed Stage Venture Capitalists is that Angel Investors typically do not invest on a full-time basis, and Angel Investors typically are making investments on their own behalf.

If things go well, it gets to a point where the team working on the startup has key members in place, the product has advanced beyond the MVP, there is meaningful customer/user traction, and revenue is early but indicative of a significant market opportunity. The team now decides that it makes sense to raise venture capital.

A seed stage venture fund will likely invest between $150,000 – $1,000,000 at a time, in financing rounds that range from $1,000,000 – $3,000,000 or so, but generally less than $5,000,000. Some funds might have requirements such as:

- Minimum investment size, of say $500,000.

- Ownership targets, of say 10%.

- Syndicate composition, preferring a syndicate that includes at least one or two other institutional seed-stage venture capital funds.

This round will likely be a priced round, and the venture fund leading the round will set the valuation, agree to a term sheet with the startup, and negotiate the final documents that will govern that round of financing.

Here are a few nuances about this segment of the startup and venture capital ecosystem.

- Founders should focus their efforts on finding and speaking with funds that have a current fund size that fits the size of the round the founders are trying to raise. What does that mean? A seed stage VC investing a $50,000,000 fund will likely set a minimum investment size of $500,000 or more as an internal rule of thumb.4 I would not spend my time pursuing a meeting with this VC if I were a founder raising a $750,000 round, for example. Why? Minimum investment size and syndicate composition would likely pose stumbling blocks. On the other hand, a seed stage VC investing from a $10,000,000 fund might be worth the time and effort I put into getting a meeting because such a fund has likely set a minimum investment amount that is less than $500,000 – say, $350,000, and may also be willing to invest as part of a syndicate that is largely filled by angels. So my $750,000 round could be filled as follows: $350,000 from a lead investor (institutional VC #1), $200,000 from another VC (institutional VC #2), $100,000 from an angel investor (angel investor #1), $50,000 from another angel investor (angel investor #2) and the remainder in $25,000 increments (from angel investors #3 and #4)

- I do not advocate completely ignoring investment professionals at larger seed-stage funds. Let’s go back to the example of a founder raising $750,000. Assume that angel investor #4 is friends with a VC at a $120,000,000 seed stage fund and offers to make an introduction because ” . . . this is the sort of stuff they love to invest in . . . ” Then that meeting is very much worth taking because it enables the founder to start building a relationship with that VC and determine if there’s an investment and personality fit, and it enables the VC to observe the progress the startup is making over time and to get a more intimate sense of the founders’ management decision-making skills. This matters because this VC could be a potential investor in a subsequent “Institutional Seed Round” in which the startup is raising $2,500,000 for example.

Inflection Point 3: Startup -> Company

If things are going well, our startup gets to the point where it now wants to raise more than $5,000,000 because the founders believe they have:

- Confirmed their primary hypotheses,

- Understand how to win customers/users, and how to generate revenues and profits,

- Need more capital to pursue sales, and

- Hire more people.

This organization is still a startup, but it has started the slow transition from being a startup to becoming a company. This transition will depend to a large extent on how successful the startup is at creating and satisfying demand for its product. This transition will probably traverse several rounds. Generally I think of Series A, B, C and D as covering the period during which a startup is building out the internal and external structures that help it become a company. How do you know a startup has become a company. Well, it starts resembling organizations to which we are often accustomed. The existence of a full complement of c-suite executives is one good indicator.

Ultimately we get to a point where, the search and discovery stage has receded far into the past, and the structures of a company have been built. All that is then left is for the company to grow by executing and scaling the business model, and generating profits.

In Sam Altman’s article “Projects and Companies” he points out that the distinction is important mainly because of how it affects the way founders behave and think about what they are doing. The underlying feature of the transition from an idea to a company is that founders should be in a learning, experimentation, and discovery mode.

Distinctions matter. There is an important difference between a startup and a company.

In a company customers are already known, the product features that matter to these customers is already known, how much they will pay for the new product or service has already been established, and the market opportunity has already been sized and is well understood. In a company the business model is already known, and most activities are designed to execute a detailed business plan.

In contrast, a startup begins with no customers, no real understanding of the features customers need, no idea what customers will be willing to pay for the product, and no knowledge of the business model that will be most suited to creating, delivering and extracting value.

Steve Blank and Bob Dorf describe The 9 Deadly Sins of The New Product Introduction Model in their book The Startup Owner’s Manual.5 These are the lessons they offer startup founders who are in the search and discover phase.

- Don’t assume you know what the customer wants – start with guesses and hypotheses. These become facts only after they have been validated with customers willing to pay for the product.

- Don’t assume you know what features to build – this follows directly from the preceding lesson, avoid building features no body cares about by first testing your assumptions about them with customers willing to pay for them.

- Don’t focus on a launch date – instead focus on building a product that customers want to pay to use. Focusing on a launch date can cause the team to place an emphasis on the wrong things, causing the startup to hurtle towards the launch date even if it does not yet know its customers, or how to educate them about its product. Also, this becomes a milestone by which the startup’s investors will judge the performance of their investment.

- Don’t emphasize execution. Rather emphasize developing and testing hypotheses, learning, and iteration – the emphasis on getting things done at a startup can lead employees to focus on execution rather than searching for answers to the guesses that the startup is operating under. Hypotheses have to be tested, and tested again. Executing on untested hypotheses is a “going-out-of-business strategy.”

- Don’t focus on a business plan, instead search for a business model – A business plan offers the great comfort of presumed certainty. The reality of a startup’s existence is one of acute uncertainty. That can be very unsettling. A startup’s founders, investors, employees, and board of directors must avoid the seduction that accompanies reliance on business plans, and the management tools that characterize the experience of large companies with known customers and well-established business models. Results of experimentation and validation tests should matter more than milestones.

- Don’t confuse traditional job titles with what a startup needs to accomplish – the traits that an individual needs in order to succeed in the environment of a startup differ significantly from those that lead to success in a large company with a known business model, a fixed business plan, known customers, and a known market. In contrast, to succeed in the startup environment an individual needs to be comfortable with chaos, flux, and “operating without a map”. The worst thing that could happen for a startup is for employees to default to behaving as they would if they were working in a large company.

- Do not execute a “Sales and Marketing” plan too early – sales and marketing can become too focused on executing to a seemingly great plan rather than learning the identity of a startup’s most profitable customers and gaining knowledge about what will spur those customers to engage in behavior that enables the startup generate revenues and profits. Consider a scenario in which a startup has gained hundreds of customers but only a tiny fraction of those customers actually make a purchase, and to make things worse a vast majority of completed purchases are made by a an even smaller number of repeat buyers. A focus on the “number of customers” might camouflage the startup’s dire need to determine what steps it needs to take in order to dramatically increase the number of paying customers.

- Don’t presume success prematurely – executing to a business plan often leads to premature scaling, even when the reality might call for the startup to hit the brakes. Expanding overhead costs before the revenue to support such costs materializes is the shortest path to disaster for a startup. Hiring, and infrastructure expansion should only happen after sales and marketing have become predictable, repeatable, and scalable processes. Moreover, startups need to be impatient for profits but patient for growth. A startup that know’s how to earn a profit can survive indefinitely.1 A startup that does not know how to earn a profit, but instead is focused on other measures of growth is playing a dangerous game of Russian roulette.

- Don’t manage by crises, that leads to a death spiral – the accumulation of all these mistakes leads to the inevitable demise of the startup that makes the mistake of operating as if it is merely a small version of a big company.

For those potential first-time founders who are grappling with the question: “Where do I start?” . . . I hope this helps.

Next? I think you should read: Paul Graham – Default Alive Or Default Dead?

Like this:

Like Loading...