The World Bank has raised fresh alarm over Nigeria’s deepening poverty crisis, disclosing that an overwhelming 75.5 percent of the rural population now lives below the poverty line.

The figure, released in its April 2025 Poverty and Equity Brief, underscores what has become a structural and worsening problem—growing inequality, stagnating incomes, and a widening gap between economic plans and lived realities.

While urban poverty remains troubling, with 41.3 percent of the population living under the international poverty threshold, rural areas appear to be bearing a disproportionate share of the burden. The numbers suggest a country increasingly split between two economic realities: one in its cities, and a more dire one in its villages, where subsistence farming remains the main source of livelihood.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

According to the report, Nigeria’s rural poor are caught in a spiral of hardship made worse by economic shocks, rising insecurity, and the long shadow of inflation. The latest estimates show over 54 percent of Nigerians are now poor, a sharp rise from the 30.9 percent recorded in the 2018/19 survey—before the COVID-19 pandemic and the series of economic crises that followed.

The report draws on data from the National Bureau of Statistics, reflecting pre-pandemic poverty levels, but notes that the country’s condition has deteriorated sharply since then. Analysts point to a string of economic missteps—subsidy removals, a botched currency reform, and stagnant productivity, as key contributors to this trend.

In its breakdown, the Bank painted a grim geographic picture. Northern Nigeria, for instance, had a poverty rate of 46.5 percent in 2018/19, compared to 13.5 percent in the South. The inequality is underlined in Nigeria’s Gini index, estimated at 35.1, revealing that wealth and opportunities are unevenly distributed across the country’s six geopolitical zones.

But it’s not just geography that divides Nigeria’s poor. Age, gender, and education have also emerged as defining fault lines. Children under 14 have a poverty rate of 72.5 percent, while 64 percent of females and 63.1 percent of males are considered poor under the lower-middle-income poverty line of $3.65 per day.

Among adults without formal education, a staggering 79.5 percent live in poverty, while the figure drops to 61.9 percent for those with primary schooling. Even a secondary school education offers little protection—half of all adults with that level of education remain poor. Only those with tertiary education show some insulation from hardship, with a 25.4 percent poverty rate, still high but significantly lower than national averages.

Beyond income, the World Bank’s report touches on multidimensional poverty indicators that suggest the situation is even more complex. Nearly one-third of Nigerians survive on less than $2.15 per day. 32.6 percent lack access to basic drinking water, 45.1 percent to proper sanitation, and 39.4 percent to electricity—an indictment of decades of failed infrastructure promises.

Education also remains a bottleneck. 17.6 percent of Nigerian adults have not completed primary education, and nearly 1 in 10 households has at least one school-aged child not enrolled in school, symptomatic of a system where public education continues to suffer from chronic underfunding and poor governance.

The report noted that poverty reduction in Nigeria had stagnated even before COVID-19, with only marginal declines since 2010. In urban areas, the World Bank said, the living standards of the poor have barely improved, while the job market continues to offer little respite.

“Jobs that would allow households to escape poverty are lacking,” it said.

Indeed, this lack of structural transformation, Nigeria’s economy remains deeply tied to oil, has made the country particularly vulnerable. Rural areas, which rely heavily on agriculture, are struggling with low productivity and rising climate threats, which the Bank warns will worsen if urgent reforms aren’t made.

“The limited availability of jobs is symptomatic of an economy beset by structural transformation constraints,” the report stated, “and the continued dependence on oil. In rural areas, livelihoods heavily rely on agricultural activities, often for subsistence, with limited productivity gains and are ill-adapted to mitigate mounting climatic challenges.”

Since the last survey in 2018/19, things have only grown worse. According to World Bank estimates, 42 million more Nigerians have fallen into poverty. While the removal of fuel subsidies and the liberalization of the naira exchange rate were intended to stabilize Nigeria’s macroeconomic environment, they have had an immediate and brutal impact on ordinary Nigerians, whose purchasing power has crumbled under runaway inflation.

“Inflation remains high, dampening consumer demand and continuing to undermine the purchasing power of Nigerians. Labor incomes have not kept up with inflation, pushing many Nigerians, particularly in urban areas, into poverty,” the Bank warned.

Amid this backdrop, the World Bank said Nigeria’s current response efforts, such as temporary cash transfers to 15 million households, are commendable, but insufficient. The urgency now, it says, is to move beyond stopgap measures.

It recommended reforms which include:

- Strengthening Nigeria’s fragmented social protection systems

- Expanding access to education and healthcare

- Investing in infrastructure to improve economic productivity

- And perhaps most critically, diversifying away from oil to foster job creation in other sectors.

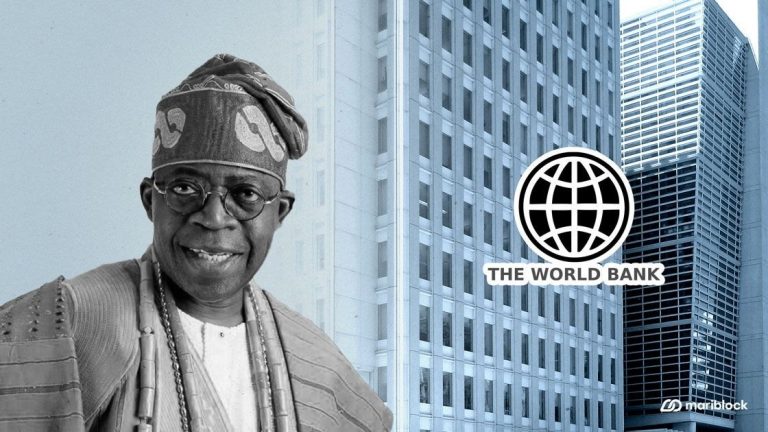

Despite successive governments repeatedly pledging to tackle poverty, the situation on the ground reveals a different story. President Bola Tinubu’s economic reforms have yet to translate into tangible relief for ordinary Nigerians, while it is believed that spending priorities remain skewed—favoring elite privileges over pro-poor investments.

The World Bank’s findings arrive at a critical juncture for Nigeria, a country with one of the fastest-growing populations in the world, but an economic structure that appears increasingly unfit for purpose. Unless urgent, sweeping reforms are carried out—not just on paper, but through actual implementation, the report suggests that the country risks entrenching a generational cycle of poverty.