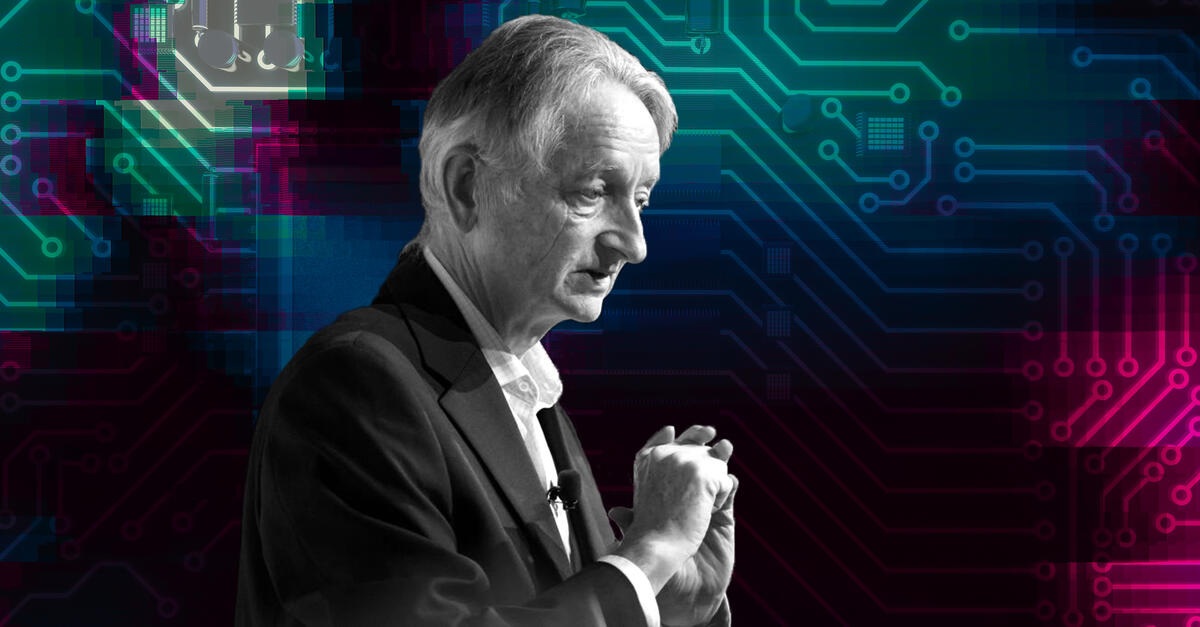

Geoffrey Hinton, the pioneering computer scientist often called the “godfather of AI” and a Nobel laureate, has issued another warning about the future of work in the age of artificial intelligence.

In a wide-ranging interview with the Financial Times, Hinton predicted that AI would trigger mass unemployment alongside soaring profits, enriching a small elite while leaving most people poorer. But crucially, he argued that the fault lies not with the technology itself, but with capitalism.

“What’s actually going to happen is rich people are going to use AI to replace workers,” Hinton said. “It’s going to create massive unemployment and a huge rise in profits. It will make a few people much richer and most people poorer. That’s not AI’s fault, that is the capitalist system.”

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 20 (June 8 – Sept 5, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

His comments echo those he gave to Fortune last month, when he accused AI companies of chasing short-term profits at the expense of preparing for the technology’s long-term societal consequences.

Entry-Level Jobs at Risk

For now, layoffs tied to AI adoption have not spiked, but early signs of disruption are emerging. Evidence is mounting that entry-level opportunities — the first rung for many recent graduates — are shrinking as companies turn to AI for repetitive tasks. A recent survey from the New York Fed found that firms using AI are more likely to retrain existing employees than fire them, but acknowledged that layoffs are expected to rise in the coming months as automation deepens.

Hinton believes that jobs performing mundane or routine tasks are the most vulnerable, while roles requiring highly specialized skills or human judgment may be safer. Healthcare, in particular, is one sector he expects to benefit rather than suffer from AI.

“If you could make doctors five times as efficient, we could all have five times as much health care for the same price,” Hinton said in June during an appearance on the Diary of a CEO YouTube series. “There’s almost no limit to how much health care people can absorb—[patients] always want more health care if there’s no cost to it.”

While some AI leaders, such as OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, have suggested a universal basic income (UBI) to soften the blow of job displacement, Hinton dismissed the idea, saying it “won’t deal with human dignity” or the intrinsic value people derive from having work.

Existential Threats and Regulation Gaps

Hinton has long warned of the dangers of AI without adequate guardrails. He estimates a 10–20% chance that advanced AI could eventually wipe out humanity after the emergence of superintelligence.

He places AI’s risks in two categories: threats inherent in the technology itself — such as runaway intelligence — and threats arising from misuse by malicious actors. For instance, he warned in his FT interview that AI could aid in the creation of bioweapons.

Hinton also criticized the Trump administration for its reluctance to regulate AI more tightly, noting that China is taking the threat more seriously. At the same time, he acknowledged AI’s upside potential, describing the current moment as unprecedented and unpredictable.

“We don’t know what is going to happen, we have no idea, and people who tell you what is going to happen are just being silly,” he said. “We are at a point in history where something amazing is happening, and it may be amazingly good, and it may be amazingly bad. We can make guesses, but things aren’t going to stay like they are.”

An Unexpected Personal Use of AI

Despite his concerns, Hinton is also an active user of AI tools. He told the FT that he uses OpenAI’s ChatGPT mainly for research. In one anecdote, he revealed that a former girlfriend once used the chatbot during their breakup: “She got the chatbot to explain how awful my behavior was and gave it to me. I didn’t think I had been a rat, so it didn’t make me feel too bad?.?.?.?I met somebody I liked more, you know how it goes,” he quipped.

Why He Really Left Google

Hinton also clarified the reasons behind his 2023 departure from Google. Media reports suggested he quit in order to speak more freely about AI’s risks, but he said the truth was more mundane.

“I left because I was 75, I could no longer program as well as I used to, and there’s a lot of stuff on Netflix I haven’t had a chance to watch,” Hinton said. “I had worked very hard for 55 years, and I felt it was time to retire?.?.?.?And I thought, since I am leaving anyway, I could talk about the risks.”

What the evidence says so far about jobs

Actual layoffs tied directly to AI remain limited for now. A recent New York Fed study covering firms in the New York–Northern New Jersey region finds AI adoption rising sharply, and that companies using AI are more likely to retrain workers than to fire them. Still, the survey documents early signs of disruption: some service firms reported scaling back hiring because of AI, and a modest share expect layoffs in the months ahead — effects concentrated at the entry and college-degree levels where recent graduates typically find work. Those patterns are consistent with Hinton’s concern that opportunities at the start of careers are already shrinking.

How other influential voices frame the trade-offs

Hinton’s capitalism critique sits beside a set of alternative — often more technocratic — proposals from other leading figures and institutions. Their responses offer contrasts in diagnosis and remedy.

Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, has publicly backed experiments with universal basic income and related pilots as a way to soften disruption while societies adapt. Altman and others in Silicon Valley argue AI could fund broader income supports or other redistributive mechanisms so the gains from automation are shared more widely; proponents frame UBI as a practical bridge while skills, education, and labor markets adjust.

Bloomberg reported on recent UBI experiments backed by groups around Altman and other tech figures, illustrating how the idea has moved from abstract to testable policy.

Bill Gates has emphasized productivity gains from AI while also urging policy responses to manage the distributional effects. Gates has pointed out that AI will make many tasks “cheaper and more accurate,” which will lower costs and boost output, but he has also proposed tools such as taxation or new financing models to ensure society captures part of that value and funds social needs created by the transition. His public discussions of a “robot tax” and other fiscal approaches put the emphasis on using public policy to rebalance gains.

Economic institutions such as the International Monetary Fund frame the issue as a policy design problem: AI can lift productivity and global output substantially, but the benefits will not be automatic or evenly distributed.

The IMF’s work recommends a suite of actions — active labor market policies, retraining at scale, tax and transfer reforms, and stronger governance of AI deployment — to manage transition risks and ensure broader gains. The Fund’s research underlines that policy choices will determine whether AI amplifies inequality or helps raise living standards.

How these views compare with Hinton’s core warning

Hinton’s framing places moral responsibility squarely on economic incentives: the same systems that produce efficiency will, under current rules, concentrate wealth unless governance and institutions change. The technocratic voices — Altman’s experiments with UBI, Gates’ fiscal proposals, the IMF’s policy toolkits — treat the problem as solvable with better policy design and public investment.

They accept automation’s productivity promise and aim to distribute its gains; Hinton accepts the productivity upside too (notably for healthcare) but is far darker on whether market forces will allow a fair outcome without deeper structural change.