Introduction

You can imagine my surprise when I was browsing my Twitter feed one night last month and came across one of Marc Andreessen’s tweetstorms. This time he was tweeting about Clayton Christensen’s Theory of Disruptive Innovation.

Coincidentally, I have been thinking about writing a blog post on the subject since the Fall of 2014 – after a string of successive meetings with startup founders in which it became starkly clear to me that they were using the term “disruption” without actually understanding what it meant, or perhaps I should say, they used the term in a context that differs markedly from my understanding of what it means.

The purpose of this blog post is to;1

- Synthesize my understanding of Disruptive Innovation as popularized by Clayton Christensen’s work,

- To examine instances in which that process has unfolded in various industries,

- To develop a framework by which I can analyze a startup founders’ claims about “being disruptive” during my conversations with them, and

- Examine extensions of, and arguments against, Clayton Christensen’s work on Disruptive Innovation

I am thinking of this from the perspective of an early stage Seed and Series A investor in technology startups, not from the perspective of a management consultant advising market incumbents about how to avoid or prevent competition.

To insure that we are on the same page; first some definitions.

Definition #1: What is a startup? A startup is a temporary organization built to search for the solution to a problem, and in the process to find a repeatable, scalable and profitable business model that is designed for incredibly fast growth.2 The defining characteristic of a startup is that of experimentation – in order to have a chance of survival every startup has to be good at performing the experiments that are necessary for the discovery of a successful business model.2

Definition #2: What is Sustaining Innovation? A “sustaining innovation” is an innovation that leads to product improvements without fundamentally changing the nature or underlying structure of the market to which it applies; it enables the same set of market competitors to serve the same customer base.3

In other words; a sustaining innovation solves a problem that is well understood within an existing market. The innovation improves performance, lowers costs and leads to incremental product improvements. The customers are easily identified, and market reaction to the innovation is predictable. Lastly, traditional business methods known within that market are sufficient to bring the innovation to market.4

Additionally;

- A sustaining innovation is evolutionary if it leads to product improvements that are gradual in nature, progressing along what might be described as a gradual step function.

- A sustaining innovation is revolutionary, discontinuous, or radical when it leads to product improvements that are dramatic and unexpected in nature, but that nonetheless leaves the market structure largely intact – even if there is a rearrangement of counterparties within the existing competitive hierarchy.

- Even the most dramatic and difficult sustaining innovations rarely lead to the failure of leading incumbents within a market.5

Definition #3: What is Disruptive Innovation? A “disruptive innovation” is one that starts out being worse in product performance in comparison to the alternative, in the immediate term. However, as time progresses the disruptive innovation leads to a significant and fundamental shift in market structure – new entrant competitors serve an entirely changed customer base.6

In other words; a disruptive innovation solves a problem that is not well understood by the market, thus creating a “new market” for the new entrant. The innovation is dramatic and game-changing in ways that initially elude the mainstream customers as well as market incumbents serving those customers. The customer is often difficult to identify at the outset, and market reaction toward the innovation is unpredictable – from the perspective of the mainstream. Traditional methods and business models that have served the market can not support the innovation.7

Additionally;

- A disruptive innovation introduces a different and “comparatively inferior” value proposition than the value proposition the existing market is accustomed to; as such

- Disruptive innovations start out being attractive only to a relatively “fringe” and “new” but altogether “unprofitable” customer base with products that are;

- “Cheaper, simpler, smaller, and more convenient” for the customers that find them most attractive at the outset, and

- These products perform so “poorly” that mainstream customers in that market will not use them, and incumbent players are happy to keep “their best, and most profitable customers” while ceding “their worst, and unprofitable customers” to the startup bringing the disruptive innovation to market, but

- Eventually the disruptive innovation leads to market shifts which cause leading incumbents to fail as the new entrants supplant them.

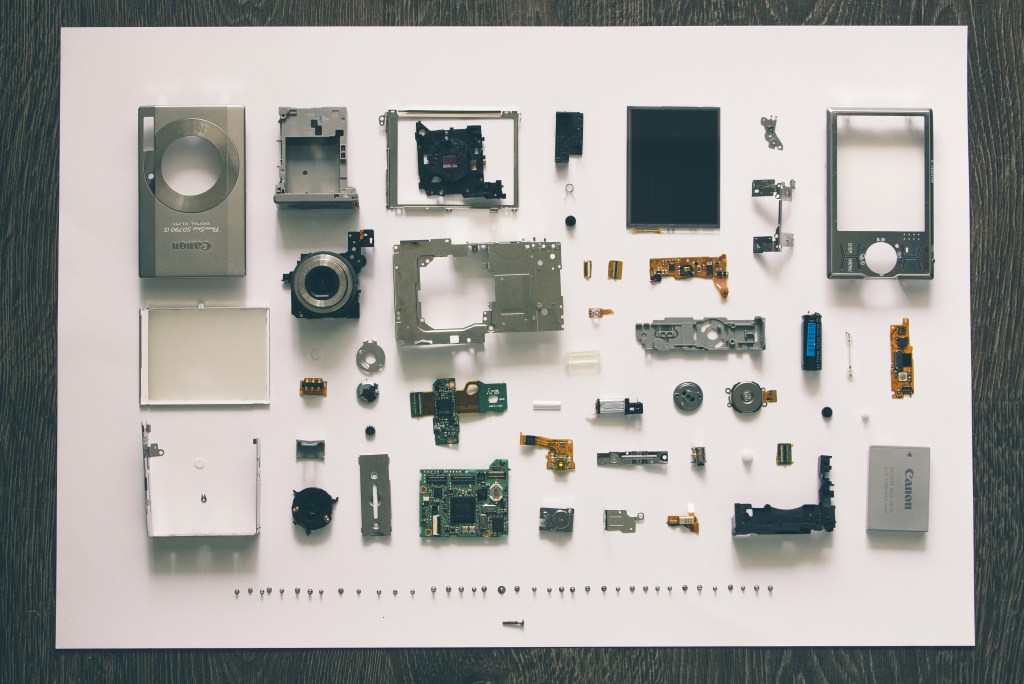

Image Credit: Vadim Sherbakov

Understanding What is Happening When a Market Undergoes Disruption

So what exactly is going on when a market experiences disruption? Contrary to what the term “disruptive innovation” suggests . . . the process is not sudden.

As Clayton Christensen states; Disruptive innovations are generally straightforward technologically. They consist of off-the-shelf components combined in a product architecture that is far simpler than existing alternatives or substitutes in a way that does not meet the needs of the core customers in an established market. They will often be derided and dismissed by incumbents as “inferior” because they offer benefits prized by an emerging class of customers in an emerging, but as yet unnoticed market. The disruptive innovation starts out being unimportant to the mainstream customer and so it is unimportant to the mainstream incumbent. 1

Mainstream customers and mainstream investors hold mainstream incumbents captive – with demands for sustaining innovations, and demands for meeting or beating financial performance metrics like internal rate of return, net present value, return on equity, return on invested capital, gross margins, net margins etc. Faced with the choice between pursuing an unprofitable emerging class of customers or doubling down in the competition for the most profitable mainstream customers in that market, management teams running mainstream incumbents do the rational thing; they double down in heated competition for profitable customers.

The disruptive innovation improves so rapidly, that it soon starts to meet the needs of segments of the mainstream customer base. As the cycle continues, it reaches a stage where the incumbents find themselves squeezed into a tiny corner of the market, driven out of it altogether, or dead.

This process describes a “low-end disruption.”

Disruptive innovation might take another form; in a “new market disruption” the startup initially sets its sights on customer segments that are not being served by mainstream incumbents within a given market. A new market disruption starts by competing “outside” of an existing market; in new use-cases, or by bringing in customers who previously did not consume because of they lacked the know-how or financial resources needed to use the incumbent product. The new market is “small and ill-defined” . . . However, as the new entrant grows and improves its product, customers begin to abandon the incumbent in favor of the disruptive innovation. Usually, the incumbent cannot compete with the new entrant because the new-market disruption is accompanied by a structurally distinct business model which makes it feasible for the new entrant but infeasible for the incumbent, for example a cost structure that is so thin that it could not support the incumbent’s fixed costs.8

What Is The Innovator’s Solution; For Early Stage Startups and Early Stage Venture Capitalists?

Of the many dimensions of business building, the challenge of creating products that large numbers of customers will buy at profitable prices screams out for accurately predictive theory.

– Clayton M. Christensen and Michael E. Raynor, The Innovator’s Solution

First: Understand Why Customers Buy What causes customers to buy a product? A startup wishing to disrupt an established market needs to be able to answer this question in a way that existing incumbents have not. The “Jobs-To-Be-Done” (JTBD) framework enables a startup to develop its product at the “circumstance” in which its customers find themselves at the time they need its product, and not directly at the circumstances. As Christensen and Raynor put it: “The critical unit of analysis is the circumstance and not the customer.”

The basic idea behind the jobs-to-be-done framework is that customers “hire” a product when they need to get a specific “job” done. The entrepreneur who understands what job the startup’s product is being hired to do can also develop an understanding of the other jobs that might be related and ancillary to the primary job. The regularity and frequency with which customers need to get that job done plays a role in product development; what features should be prioritized? Which features should be de-prioritized even though they at first seemed important? How should the product’s value proposition be communicated? What other features should be built so that customers need not combine several different products in order to complete the job, or if they do how does the startup capture those markets too? 2

In my opinion startups stand an even better chance of success if they can combine the JTBD framework with an understanding what broad needs their product satisfies for their customers using the parameters laid out by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. This matters especially in the determination of how a startup should communicate the product’s value proposition to its target customer base. An incongruence between the startups marketing message and the customers’ psychological notions about the product will lead to missed opportunities for the startup. It might also lead a startup to chase after the wrong customer base at the outset.9

When new ventures are expected to generate profit relatively quickly, management is forced to test as quickly as possible the assumption that customers will be happy to pay a profitable price for the product.

– Clayton M. Christensen and Michael E. Raynor, The Innovator’s Solution

Second: Be Patient For Growth But Impatient For Profits The investors and founders of a startup that claims to be disrupting a market must quickly test if the market dynamics the startup must confront are such that it can earn a profit given its business model. This is important because it indicates that for those startups that answer those questions positively, it is possible for them to pursue growth in a way that is healthy and sustainable irrespective of the magnitude of the growth.

The Startup Genome Report reached conclusions that support this notion. In an extra to the 2011 version of that report they study the effect of premature scaling on the longevity of startups. They found that 70% of the 3200+ high-growth technology startups scaled prematurely along some business model dimension.

Before delving deeper into the findings from the Startup Genome Report, we should understand “Product-Market Fit“. An early stage startup is approaching the product-market fit milestone when demand for its product at a price that is profitable for the startup’s business model, begins to outstrip the demand that could have been explained by its marketing, sales, advertising, and PR efforts.

Product/market fit means being in a good market with a product that can satisfy that market.

You can always feel when product/market fit isn’t happening.The customers aren’t quite getting value out of the product, word of mouth isn’t spreading, usage isn’t growing that fast, press reviews are kind of “blah”, the sales cycle takes too long, and lots of deals never close.

And you can always feel product/market fit when it’s happening. The customers are buying the product just as fast as you can make it — or usage is growing just as fast as you can add more servers. Money from customers is piling up in your company checking account. You’re hiring sales and customer support staff as fast as you can. Reporters are calling because they’ve heard about your hot new thing and they want to talk to you about it. You start getting entrepreneur of the year awards from Harvard Business School. Investment bankers are staking out your house. You could eat free for a year at Buck’s.

– Marc Andreesen10

In other words, the product-market fit milestone is that milestone at which we start to realize that the startup has an opportunity to grow in sustainable and profitable way. As organic demand for the product starts to overwhelm the startup – i.e. as the market starts to pull the product out of the startup, that is the point at which it makes sense for investors to become impatient for growth. Before Product-Market Fit (BPMF) a startup must “push” its product onto the market – customers and revenue grow in direct, linear proportion to sales and marketing expense. After Product-Market Fit (APMF) the market “pulls” the product out of the startup – customers and revenue grow positively, disproportionately, and exponentially out of proportion to any sales and marketing expense incurred by the startup. Investors and startup founders should become impatient for growth when the startup is in the APMF phase of its life-cycle. This approach should hopefully avoid situations like: Case Study: Fab – How Did That Happen?

According to Startup Genome Report Extra on Premature Scaling:

Note: They use the term “inconsistent startups” to describe startups that scale prematurely and “consistent startups” to describe startups that scale successfully.

- 74% of startups scale prematurely.

- Startups that scale appropriately grow about 20x faster than startups that do not.

- Inconsistent startups that raise funding from investors tend to be valued 2x as much as consistent startups and raise about 3x as much capital prior to failing.

- Inconsistent startups have teams that are 3x the size of the teams at consistent startups at the same stage.

- However, once they get to the scaling stage, consistent startups have teams that are 1.38x the size teams at inconsistent startups.

- Consistent startups take 1.76x as much time to reach the scale-stage team size than their inconsistent peers.

- Inconsistent startups are 2.3x more likely to spend more than one standard deviation more than the average cost to acquire a customer than their consistent peers.

- Inconsistent startups write 3.4x more lines of code and 2.25x more lines of code in the discovery and efficiency stages of their life-cycle.1 Discovery and efficiency are the first and third stages of the startup lifecycle, as described in the report.11

- A majority of inconsistent startups are more likely to be efficiently executing irrelevant things at the Discovery, Validation, and Efficiency stages of their life cycle, while a majority of consistent startups seek product-market fit during those stages.

- The following attributes have no correlation to the likelihood that a startup will be inconsistent or consistent: market size, product release cycles, educational attainment, gender, age, length of time over which co-founders have known one another, location, tools used to track KPIs etc.

What are some of the mistakes that inconsistent startups make as they travel from launch to dysfunctional scaling to failure? The Startup Genome Report provides some examples:

Customer

- Spend too much on customer acquisition BPMF and before discovering a profitable, repeatable and scalable business model, and

- Attempt to ameliorate that problem with marketing, press, and public appearances.

Product

- Build a “perfect product” before knowing enough about the “Problem-Solution Fit”, and

- Investing into scaling the product BPMF, and

- Focusing on advanced product features which are later proven to be unimportant to customers.

Team

- Growing the team too fast,

- Hiring specialists and managers too early and not having enough people who can or will actually do the work that needs to get done, and

- Having too much hierarchy too early.

Finance

- Raising too little money at the outset,

- Raising too much money.12

Business Model

- Not spending enough time developing the business model, and only realizing after the fact that revenues will never support the startup’s cost structure.

- Focussing too much on maximizing profit too early in the startup’s life-cycle,

- Executing without observing and analysing the input from customers and the market, and

- Failing to pivot appropriately in the face of changing market conditions that are relevant to the startups based on its discovery-focused experiments.

The 4 Stages Of Disruption

In his article, Four Stages of Disruption, Steven Sinofsky describes the process of disruption using an analogy to the well known and well understood rubric for understanding the experience of someone experiencing significant loss.

The 4 stages of disruption are:

- Disruption: A new product appears on the market but is seen to be inferior to the existing mainstream alternative.

- Evolution: The new product undergoes rapid sustaining innovations.

- Convergence: The new product is now seen as a plausible replacement for the incumbent mainstream product because it has undergone enough sustaining innovations to make it comparable to the incumbent.

- Reimagination: During this stage there is a complete re-examination of the assumptions on which the market operates and new products are brought to market.

Sinofsky describes them as a process, as shown in the following diagram:

I think the framework is better understood as a cycle; because every incumbent must face a new entrant or new entrants seeking to disrupt the market and eventually every successful new entrant that disrupts a market itself becomes an incumbent facing disruption by a successive hoard of disruptive new entrants. The cycle is ongoing and continuous, and is driven by more than simple advances in technology. Human behavior plays a central role in shaping the cycle that creates room for disruption to occur because our tastes change over time, and as time progresses we begin to value things that we did not value in the past, and it is that insight into the confluence between technology and human behavior that enables certain entrepreneurs to build startups that become industry disruptors.

How Did That Happen? – Disruption in Action; Industries

Digital Cameras vs. Film Photography: Digital cameras threatened to disrupt film photography, but they mainly represented a sustaining innovation – largely improving on existing form factors already in use in that market and fulfilling the needs of people one would consider casual or professional photographers. It was not until digital camera technology was integrated into smart-phones that the photography market started to experience disruption. They appealed to anyone who had the desire to take a picture, photographer or not, it did not matter. As Craig Mod argues in his 2013 New Yorker article Goodbye, Cameras: “In the same way that the transition from film to digital is now taken for granted, the shift from cameras to networked devices with lenses should be obvious.” Standalone cameras are simply no longer good enough because: “They no longer capture the whole picture.” Kodak’s demise follows the classic format of every great incumbent that has fallen into obscurity in the face of an onslaught from new entrants. Kodak was itself a disruptor at one point – taking photography out of the sole preserve of professionals and putting it in the hands of every casual photographer seeking to preserve memorable moments. In his 2012 Wall Street Journal article, Kamal Munir outlines the rise and fall of Kodak in The Demise of Kodak: Five Reasons. It is important to note that Kodak developed technology for a digital camera in 1975, yet it failed to understand why customers bought its products and so failed to shift its business model as aggressively as it could have to avoid the fate that began staring it it in the face in 1975, nearly 4 decades before it filed for bankruptcy.13

Mobile Phones vs. Fixed Line Telephones: One sign that mobile and broadband telephony is disrupting fixed line telephony is the European Commission’s 2014 decision to stop regulating fixed line telephony. The situation for fixed line telephony is no different with telephone companies announcing that they are abandoning their landline telephone infrastructure in favor of mobile and broadband phone service. Their reaction is being driven by consumer’s willingness to rid themselves of landlines in favor of cellphones for individual personal use and/or VOIP-enabled phones at home. Liquid Crystals were first discovered by the Austrian physicist Friedrich Reinitzer in 1888. Nearly 7 decades later, engineers and scientists at RCA were conducting research that led them to file the first LCD patent on November 9, 1962. The USPTO granted them the patent on May 30, 1967. However, RCA did not move aggressively enough to make the LCD technology that had been developed by its employees the center of its business model.

Liquid Crystal Displays vs. Cathode Ray Tubes: The emergence of LCD technology marked the beginning of the end for CRT technology in the TV market. The technology that led to the development of LCD televisions originated in 1888, when an Austrian Physicist, Friedrich Reinitzer discovered the strange behavior of cholesteryl-benzoate. Nearly 4 decades later, scientists and engineers working at RCA filed a patent application based on LCD technology on Nov 9, 1962. It was granted on May 30, 1967. Predictably, RCA did not do much with its head-start in the development of LCD technology, instead it gave up its advantage to Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese upstarts.

Find more statistics at Statista

How Did That Happen? – Disruption in Action; Companies/Products

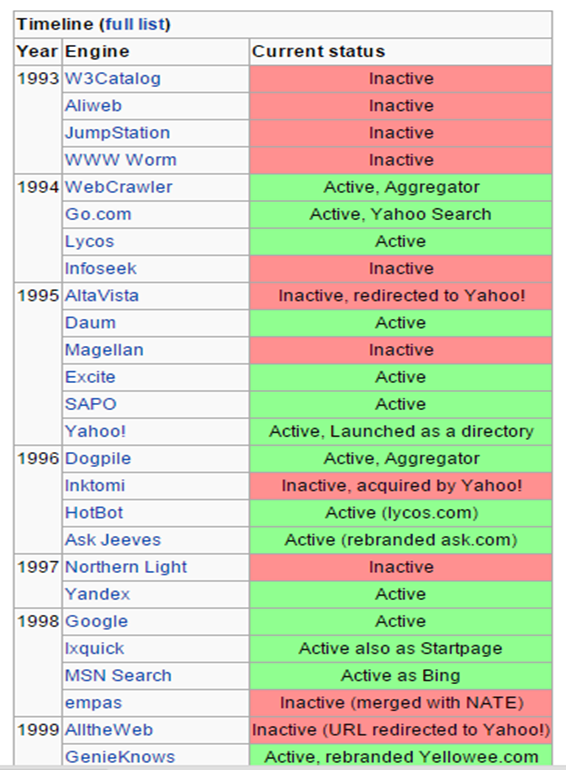

Google – Launching Sustaining and Disruptive Innovations:

View image on Twitter

While Google’s innovation in search are impressive, and helped it win that market at the expense of other search engines, it gained near absolute dominance in that market by developing a sustaining innovation in the form of its PageRank Algorithm, which is described in the paper by Sergey Brin and Lawrence Page: The Anatomy Of A Large Hypertextual Web Search Engine.

Find more statistics at Statista

Rather, the industry that has been disrupted by Google is the online advertising market. Describing this in his article “What Disrupt Really Means” Andy Rachleff writes: “It was AdWords, its advertising service. In contrast with Yahoo, which required advertisers to spend at least $5,000 to create a compelling banner ad and $10,000 for a minimum ad purchase, Google offered a self-service ad product for as little as $1. The initial AdWords customers were startups that couldn’t afford to advertise on Yahoo. A five-word text ad offered inferior fidelity compared with a display ad, but Google enabled a whole new audience to advertise online. A classic new-market disruption. Most have forgotten that Google added significant capability to its advertising service over time and then used its much-lower-cost business model (enabled by self-service) to pursue classic Internet advertisers. Thus it evolved into a low-end disruption.”

Find more statistics at Statista Salesforce – Launching New Market and Low-End Disruptions: When Salesforce launched in 1999 it did so as a software-as-a-service (SaaS) platform that enabled companies that needed sales management software but could not afford the cost of annual multimilion dollar licenses for the mainstream products of the day. It’s initial product was lacking in features, and unreliable for the mainstream customers of the incumbent players in the CRM software market at that time. It built its business on non-consumption. As time progressed and its product matured in terms of reliability and features, Salesforce caused a low-end disruption as customers adopted its product while abandoning the more expensive CRM products sold by CRM market incumbents like Siebel Systems, Amdocs, E.piphany, PeopleSoft, and SAP. Find more statistics at Statista Apple: Has Apple launched any disruptive innovations? Not if you asked Clayton Christensen in 2006 or again in 2007, or even in 2012. Yet I suspect that Nokia and Research in Motion feel differently about that question. The chart below is instructive. Apple’s products have not been disruptive in the way that one might think of disruption if one adheres strictly to the line of analysis followed by Clayton Christensen and his collaborators. Perhaps one can argue that the iPod, the iPhone, and the iPad, each taken individually represents a sustaining innovation in the personal music player, the mobile phone, and the personal computer markets respectively. However, when one combines each of those products with the other elements in Apple’s product lineup there’s no denying that Apple has been disruptive to more than one industry. The “iPod + iTunes” has reshaped how people consume music, and has upended the music industry. The iPhone has led to a rethinking of what people expect from a mobile phone, and “iPod + iTunes + iPhone + AppStore” is responsible for the demise of Nokia and Research in Motion’s Blackberry as it has redefined how people consume media of all types. The “iPad + AppStore” combination is redefining how people consume media of all types, and redefining the relationship people have with their personal and laptop computers. Apple demonstrates the power of technology + design + branding + marketing as a powerful force in the process of disrupting established industries in consumer markets.14 Find more statistics at Statista You will find more statistics at Statista Netflix: At the outset Netflix seemed like a joke to executives at Blockbuster which dominated the US market for home-movie and video-game rental services, reaching its peak with 60,000 employees and 9,000 physical stores in 2004 after its launch on october 19, 1985. Netflix was founded in 1997 and started out as a flat-rate DVD-by-mail service in the United States using the United States Postal Service as its distribution channel. Presumably, the idea for Netflix was born after Reed Hastings, one of its co-founders was hit with a $40 late-fee after returning a DVD to Blockbuster well after its due date.

Order Processing & Shipping Center (Image Credit: Netflix)

Order Processing & Shipping Center: Sleeve Labels (Image Credit: Netflix)

As you might imagine, executives at Blockbuster did not see the threat posed by Netflix and passed on 3 opportunities to buy Netflix for $50 Million. They failed to understand that people would rather not pay exorbitant late fees and that people valued the convenience of dropping the DVD from Netflix in the mail more than they enjoyed driving to Blockbuster’s physical retail stores. In other words; Netflix fulfilled the JTBD of “entertain me at home with something better than my options on TV” more conveniently than Blockbuster. The challenge that netflix must now face is how that original JTBD that it was hired to do by consumers is changing given the proliferation of mobile devices and the shift in consumer preferences away from physical media towards streaming media. You will find more statistics at Statista

But management and vision are two separate things. We had the option to buy Netflix for $50 million and we didn’t do it. They were losing money. They came around a few times. – Former High-ranking Blockbuster Executive15

To anyone that ever rented a movie from BLOCKBUSTER, thank you for your patronage & allowing us to help you make it a BLOCKBUSTER night. — Blockbuster (@blockbuster) November 10, 2013

Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy in 2013. Today Netflix is streamed online through many internet-enabled smart tvs, streaming media players, game consoles, set-top boxes, blu-ray players, smartphones and tablets, as well as personal and laptop computers.

What Common Traits Do the Startup Founders Who Lead Disruptive Startups Share?

Disruptive innovation is built on much more than technology innovation. The startups that go on to disrupt markets combine innovation in technology with innovative approaches to market segmentation, product positioning, marketing strategy, business model innovation, business strategy, corporate strategy, customer psychology, and organizational design and culture.

As an investor in early stage technology startups that are still in the searching for and trying to validate a repeatable, profitable, and scalable business model it is critical that I become good at recognizing startup founders who can successfully see disruption through to a profitable harvest for the founders, and the LPs to whom I am responsible.

According to The Innovator’s DNA, startup founders capable of leading disruptive new market entrants display the following traits:

- Association: They make connections between seemingly disparate areas of knowledge, leading them to novel conclusions that elude other people.

- Questioning: They exhibit a passion for questioning the status quo.

- Observing: They learn by watching the world around them more closely than their peers and competitors.

- Networking: They have a social network that is wide and diverse, which enables them to test their own ideas as well as seek ideas from people who may see the world from a distinctly different point of view.

- Experimenting: They continuously test their assumptions and hypotheses by unceasingly exploring the world intellectually and experientially.

These skills are echoed in The Creator’s Code, which describes extraordinary entrepreneurs as people who:

- Find The Gap: by staying alert enough to spot opportunities that elude other people by transplanting ideas across divides, merging disparate concepts, or designing new ways forward.

- Drive For Daylight: by staying focused on the future, and making choices today on the basis of where they see the market going instead of where the market has been.

- Fly The OODA Loop: by continuously and rapidly updating their assumptions and hypotheses through the Observe, Orient, Decide, and Act framework. Fast cycle iteration helps them gain an edge over their competition, and catchup with the mainstream market incumbents.16

- Fail Wisely: by preferring a series of small failures over a few catastrophic setbacks by placing small bets to test new ideas in order to gain further insight before they place big bets. By doing this they create organizations that learn how to turn failure into success and develop an inbuilt structural resilience.

- Network Minds: by harvesting the knowledge and brainpower from cognitively and experientially diverse individuals they develop unique approaches to solving multifaceted problems, problems whose solution might elude competitors.

- Gift Small Goods: by behaving generously towards others they strengthen relationships and build goodwill towards themselves and the organizations that they lead.

In The Questions Every Entrepreneur Must Answer, Amar Bhidé outlines a number of questions the feels every entrepreneur must answer in order to determine fit of the entrepreneur to the startup venture and of the startup venture to its context.17 The questions are as follows;

- Where does the entrepreneur want to go?

- What kind of enterprise does the entrepreneur need to build in order to get there?

- What risks and sacrifices does such an enterprise demand?

- Can the entrepreneur accept those risks and sacrifices?

- How will the entrepreneur and the startup get there?

- Is there a strategy that can get the startup there?

- Can that strategy generate sufficient profits and growth within a time-frame that make sense for the entrepreneur and for the startup’s investors?

- Is the strategy, and the startup’s business model defensible and sustainable?18

- Are the goals for growth too conservative, or too aggressive?

- Can the founder or co-founders do it?

- Do they have the right resources and relationships?

- How strong is the relationship between the co-founders with one another, how strong is the organization’s team cohesion?

- Can the founder play her role?

The Role of Experts in Predicting The Success or Failure of Disruptive Innovations

Early stage investors often rely on the advice of subject matter experts as part of the due diligence process. Experts are great for determining if the technical innovation works as the founders say it does, however where investors can go wildly wrong is when they rely on subject matter experts for investment recommendations for disruptive innovations.

It should be obvious by now that most experts are poorly placed to offer advice that will be seen as correct when examined in hindsight if they are faced with a disruptive innovation.

The Only things we really hate are unfamiliar things.

– Samuel Butler, Life and Habit

The difficulty subject matter experts face in predicting how markets will evolve is captured in The Lexicon of Musical Invective, where the author captures the vituperous reactions of music critics to works that are now widely considered as masterpieces in the pantheon of Western music history. Why did these experts fail? They did not allow for the possibility that the future might differ from the present in which they were performing their analysis, nor did they allow for the possibility that people’s tastes in music would evolve away from what they had grown accustomed.

Experts experience too much cognitive dissonance when they have to make an investment recommendation regarding a disruptive innovation; what does it mean for their personal career security, what does that mean for the skills that they have worked so hard and so long to accumulate, what does that mean for their employer’s business?

Moreover, the fact that an individual is an expert in the technology behind the disruptive innovation does not mean that the same individual is an expert in all the other disciplines that are required to turn the technological innovation into a disruptive innovation.

Here are a few examples of instances in which experts got things horribly wrong:19

- In 1977 Ken Olson said: “There is no reason anyone would want a computer in their home.” He was an engineer by training, and president, chairman and founder of Digital Equipment Corporation. Microsoft and Apple were startups.

- In 1956 Herbert Simon said: “Machines will be capable, within twenty years, of doing any work a man can do.” He made this statement after attending an AI conference at Dartmouth.

- In 1946 Darryl Zanuck said: “Television won’t be able to hold on to any market it captures after the first six months. People will soon get tired of staring at a plywood box every night.” He was a Hollywood magnate.

- In 1995 Robert Metcalfe said: “I predict the Internet will soon go spectacularly supernova and in 1996 catastrophically collapse.” He co-invented Ethernet technology and co-founded 3Com in 1979 with 3 other people. 3Com develops computer network products.

- In 1995 Clifford Stoll said: “The truth is no online database will replace your daily newspaper, no CD-ROM can take the place of a competent teacher and no computer network will change the way government works.” He was an astronomer, a hacker, and author, and a computer geek.

- In 2007 Steve Balmer said: “There’s no chance that the iPhone is going to get any significant market share.” He was the CEO of Microsoft.20

Criticisms of Clayton Christensen’s Theory of Disruptive Innovation

- In her 2014 New Yorker article; The Disruption Machine: What The Gospel of Innovation Get’s Wrong,JillLepore argues that:

- The theory is based on handpicked case studies, and it is not clear that these case studies are provide a sound basis upon which to build a theory.

- What Christensen describes as “disruption” can often be more accurately described as “bad management”

- The theory of disruption is built on retrospective analysis, it is unclear how useful it is in predicting how events will unfold.

- In his 2013 blog post: What Clayton Christensen Got Wrong, Ben Thompson examined the theory of disruption in the context of Apple’s introduction of the iPod, and later the iPhone. He argues that:

- The theory works well when we consider new market disruptions, but fails when we consider low-end disruptions, in consumer markets.

- The theory fails because consumers do not behave rationally.

- The theory fails to account for product attributes that cannot be documented but which consumers prize highly, all thing being equal.

- Vertical integration is a competitive advantage in consumer markets, because it allows vertically integrated producers to exert control over product attributes that customers value, but which would be near-impossible to control using a modular production framework.

Closing Thoughts

- The ideas on which “disruptive innovation” is built are not inviolable and permanent laws of nature. Early stage investors and startup founders should subject them to testing on a frequent basis. Disruption works in different ways in consumer markets than it does in enterprise, or business to business markets.

- Startup founders and their investors should combine Clayton Christensen’s ideas with those of Michael Porter in order to build a more complete strategic plan that can stand the vicissitudes of competition from the startup’s peers and the reaction from mainstream market incumbents.

- Good strategy is not a substitute for good management. Good strategy does not make good management obsolete.

- Building a better mousetrap is not necessarily the path to disruptive innovation and winning the market in which a startup is a new entrant.

- Low end disruptions almost always begin with a product that is significantly inferior in comparison to the product embraced by the mainstream market. Low end disruptions also have to be simpler, cheaper or more convenient than the mainstream product.

- New market disruptions do not necessarily have to be less expensive than the comparable product that is embraced by the mainstream market.

- Disruptive innovation entails much more than technological disruption. Incumbents can compete with technological disruption, and they always win in those scenarios. To succeed, startups seeking to disrupt a market must design business models that support their effort to bring their technological innovation to market and make it impossible for the mainstream market incumbents to respond in a manner that causes the startup to fail prematurely.

- The kernel of disruptive innovation is an insight that the mainstream market has ignored.

- Beware of investment advice from subject matter experts as it pertains to potentially disruptive startups. Test your biases against what can be proved by the market niche that the startup is first going to enter.

Further Reading

Blog Posts & Articles

- What “Disrupt” Really Means – Andy Rachleff

- The Four Stages of Disruption – Steven Sinofsky

- Marketing Myopia – Theodore Levitt, original 1960 HBR article

- Marketing Myopia – Theodore Levitt, 2004 HBR update

- How Disruption Happens – Greg Satell

- Good Disruption / Bad Disruption – Greg Satell

- Did RCA Have To Be Sold? – L.J. Davis

- What Clayton Christensen Got Wrong – Ben Thompson

- Clayton Christensen Becomes His Own Devil’s Advocate – Jean-Louis Gassée

- The Disruption Machine: What The Gospel of Innovation Gets Wrong – Jill Lepore

- Disruptive Business Strategy: What is Steve Jobs Really Up To? – Paul Paetz

- Clayton Christensen Responds to New Yorker Takedown of “Disruptive Innovation” – Drake Bennet

- How Useful Is The Theory of Disruptive Innovation? – Andrew A. King and Baljir Baatartogtokh, MIT Sloan Management Review Fall 2015 Issue

- What Is Disruptive Innovation? – Clayton Christensen et al, HBR December 2015 Issue

- Patterns of Disruption: Anticipating Disruptive Strategies of Market Entrants – John Hagel et al

White Papers

- Time To Market Cap Report

- Startup Genome Report Extra on Premature Scaling [PDF]

- Netflix: Disrupting Blockbuster [PDF]

Books

- The Innovator’s Dilemma

- The Innovator’s Solution

- The Innovator’s DNA

- Seeing What’s Next

- The Lean Entrepreneur

- What Customers Want

- The Creators Code

- The Entrepreneurial Venture

- Disruption By Design

- Any errors in appropriately citing my sources are entirely mine. Let me know what you object to, and how I might fix the problem. Any data in this post is only as reliable as the sources from which I obtained them. ?

- I am paraphrasing Steve Blank and Bob Dorf, and the definition they provide in their book The Startup Owner’s Manual: The Step-by-Step Guide for Building a Great Company. I have modified their definition with an element from a discussion in which Paul Graham, founder of Y Combinator, discusses the startups that Y Combinator supports. ?

- Clayton M. Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma. 2006 Collins Business Essentials Edition. ?

- Brant Cooper and Patrick Vlaskovits, The Lean Entrepreneur. Wiley, 2013, pp. xx. ?

- Clayton M. Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma. 2006 Collins Business Essentials Edition, pp. xviii. ?

- Ibid. ?

- Brant Cooper and Patrick Vlaskovits, The Lean Entrepreneur. Wiley, 2013, pp. xx. ?

- Clayton M. Christensen and Michael E. Raynor, The Innovator’s Solution. 2003, Harvard Business School Publishing, pp. 45. ?

- Startups building products for the enterprise customer should be able to develop an analogous framework, assuming one does not already exist. ?

- Marc Anrdeesen, Product/Market Fit, Jun 25, 2007. Accessed on Jul 18, 2015 at http://web.stanford.edu/class/ee204/ProductMarketFit.html ?

- In their report they describe the stages of a startup’s life-cycle as Discovery, Validation, Efficiency, Scale, Sustenance, and Conversation. The report covers the first four. ?

- This is a risk for early stage investors as well as startups. ?

- Theodore Levitt’s seminal HBR article “Marketing Myopia” first introduced this concept in 1960. You should read the original article as well as this update from 2004. ?

- It is worth noting that Clayton Christensen’s analysis and research focuses on business-to-business markets. ?

- Marc Graser, Epic Fail: How Blockbuster Could Have Owned Netflix. Nov 12, 2013, accessed on Jul 18, 2015 at http://variety.com/2013/biz/news/epic-fail-how-blockbuster-could-have-owned-netflix-1200823443/ ?

- See statements like: “Move fast and break things.” or “Let chaos reign.” ?

- Amar Bhidé,The Questions Every Entrepreneur Must Answer. From The Entrepreneurial Venture, readings selected by William A. Sahlman et al. 2nd edition, pp. 65 – 79. ?

- I have discussed economic moats here: Revisiting What I Know About Network Effects & Startups and here: Revisiting What I Know About Switching Costs & Startups ?

- Adapted from Top 10 Bad Tech Predictions, by Gordon Globe. Nov 4, 2012, accessed on Jul 19, 2015 at http://www.digitaltrends.com/features/top-10-bad-tech-predictions/5/ ?

- Mark Spoonauer, 10 Worst Tech Predictions of All Time. Aug 7, 2013. Accessed online on Jul 19, 2015 at http://blog.laptopmag.com/10-worst-tech-predictions-of-all-time ?