This post is the fourth in a series I am devoting to the examination of viral marketing.1 I tried to define the term in Part I, and examined how Hotmail and Dropbox each grew, in Part II and Part III respectively.

The formula in the image above is widely used to model the growth of users of a website or an app. It has been popularised through a series of posts by David Skok.2 Kevin Lawler explained how the formula is derived.3 Furthermore, Andrew Chen and others, investors and entrepreneurs alike, have written several blog posts about virality and viral marketing that build on this formula.

In this post I will state the problem that one is trying to solve when one sets out to model viral growth. Then I will examine this formula within that context. Valerie Coffman has already done a great job of examining the flaws in this formula.4 For the most part I will reiterate points that she has already made in her post.

The modeling problem: The fundamental research questions one wants to answer by modeling the viral growth of an app, website or some other digital product are these:5 If one person in a population of potential users adopts a product, how will the average number of users of that product change over time? How large could that user base ultimately become? What factors influence the growth of the number of users over time?

The model above, which I will call the Skok-Reiss Virality Model, uses the following variables in modeling viral growth; t represents time, the function U(t) represents the number of users at a specific time and U(0) is the number of users at the outset, K represents the viral coefficient, p represents the cycle time, the amount of time it takes a new user to try a product and then send out invitations to other potential new users, I represents the number of invitations each new user sends out, and C represents the rate at which people who receive a new invitation convert to become actual new users of the product. The quotient t/p represents the number of invitation cycles that occur within each unit of time.6

A key variable in the Skok-Reiss Virality Model is the viral coefficient, K. The best definition of that variable as it is applied in viral marketing is given by Eric Ries:

Like the other engines of growth, the viral engine is powered by a feedback loop that can be quantified. It is called the viral loop, and its speed is determined by a single mathematical term called the viral coefficient. The higher this coefficient is, the faster the product will spread. The viral coefficient measures how many new customers will use a product as a consequence of each new customer who signs up. Put another way, how many friends will each customer bring with him or her? Since each friend is also a new customer, he or she has an opportunity to recruit yet more friends.7

The Skok-Reiss Virality Model has a number of limitations.

First, the model does not specify the size of the market. Phrased another way, in the long run how many people are favorably predisposed to adopting this product once they have been exposed to it by someone they know? As Valerie Coffman points out this is not an inconsequential question because viral growth quickly leads to market saturation. Market saturation in turn reduces the viral coefficient. In more concrete terms, the more time elapses and the larger the proportion of people who have already heard about a product but have not yet become users of that product, the less likely it is that such people will remain as susceptible to becoming new users of the product as they were at the outset of the process. In a sense, exposure without adoption leads to immunity to future adoption. Intuitively, we would expect that market saturation imposes a limit on how large U(t) can become as t becomes infinitely large. However, as it has been formulated, the Skok-Reiss Virality Model suggests that U(t) becomes infinitely large as t approaches infinity.8

Second, the model assumes that the market is one in which people adopt a product and then use that product for ever. In Valerie Coffman’s words the Skok-Reiss Virality Model assumes that “there’s no churn in the customer base – once a customer, always a customer.” In reality the market is more likely to be one in which certain people might initially become users of the product, but then abandon it at some point in the future.9

To understand why the Skok-Reiss formulation is problematic in this sense one needs to understand and be able to describe three types of populations. A hypothetical population is one that is completely made up for the purpose of studying a specific research question. A hypothetical population typically does not reflect reality. A closed population is one in which there is no entry or exit. In certain instances a closed population is defined such that changes to the size of the closed population occur only through birth or death. In other instances a closed population is defined such that birth and death do not occur. An open population is one in which population growth is affected by birth, death, immigration and emigration. The concept of churn is important because it makes it possible for a model of viral growth to more closely resemble reality by making assumptions about; birth – an existing user brings in more users, death – existing users who adopted the product through an invitation abandon the product, immigration – new users stumble upon the product and adopt it without an invitation from an existing user, and emigration – existing users who adopted the product without an invitation abandon the product.

These two problems with the Skok-Reiss Virality Model make it unlikely that the model produces sufficiently reliable answers to the first two research questions that people modeling viral growth seek to answer.

Third, the model assumes that each user sends out a single batch of invitations after a period of time p. The assumption that each user sends out a single batch of invitations is suspect. Rather, when a user first encounters the product and enjoys the initial first few interactions with the product that user will probably send the first batch of invitations to only a few close friends and relatives. As time progresses and the user becomes more trusting of the product’s developer the user might then send a subsequent batch of invitations to a wider circle of friends and social acquaintances. Eventually the circle of people that the user sends invitations to might grow to include professional and business associates. Finally, it will get to the point where that specific product or others like it are so widely known that the average user does not send out invitations. This is the point of market saturation, at which the researcher would expect to start seeing a decline in the viral coefficient. It is not also clear that the first invitation as well as subsequent invitations, if the model accounted for them, happen at the same frequency.10

Last, the Skok-Reiss model makes the error of assuming that two very different processes that form the basis for viral growth happen on a similar timescale. To use Valerie Coffman’s words, the model assumes synchronicity when it should not. The first process is that by which individual users of the product attract new users by word of mouth and through in-product invitation mechanics. The variable in the Skok-Reiss model that reflects this phenomenon is the cycle time. Though as we have pointed out, the way it is formulated falls short of adequately reflecting what one might intuitively expect to observe in reality. The second process is that by which the product’s total user base experiences significant jumps in size. Over time the nature of the growth that this process leads to is seen to resemble exponential or compound growth. This process is driven by actions of the product developer that differ from, but complement, the actions of individual users in the first process.11 The Skok-Reiss model does not adequately differentiate between these two different but complementary processes.

As a result discussions about tactics for achieving viral growth might be flawed, and could lead to disappointing results if they are based on a naive understanding of the Skok-Reiss Virality Model. Indeed, it is often suggested that cycle time is the most important lever that one should focus on in order to achieve viral growth. In David Skok’s words;

Shortening the cycle time has a far bigger effect than increasing the viral coefficient!

Let’s examine that statement with some algebra.

First, what would we expect to happen to U(t) if we let p become infinitesimally small and hold everything else constant? As the back of the envelope analysis below suggests we expect the number of users at any given time to become infinitely large as we make the cycle time infinitesimally small. So far so good.

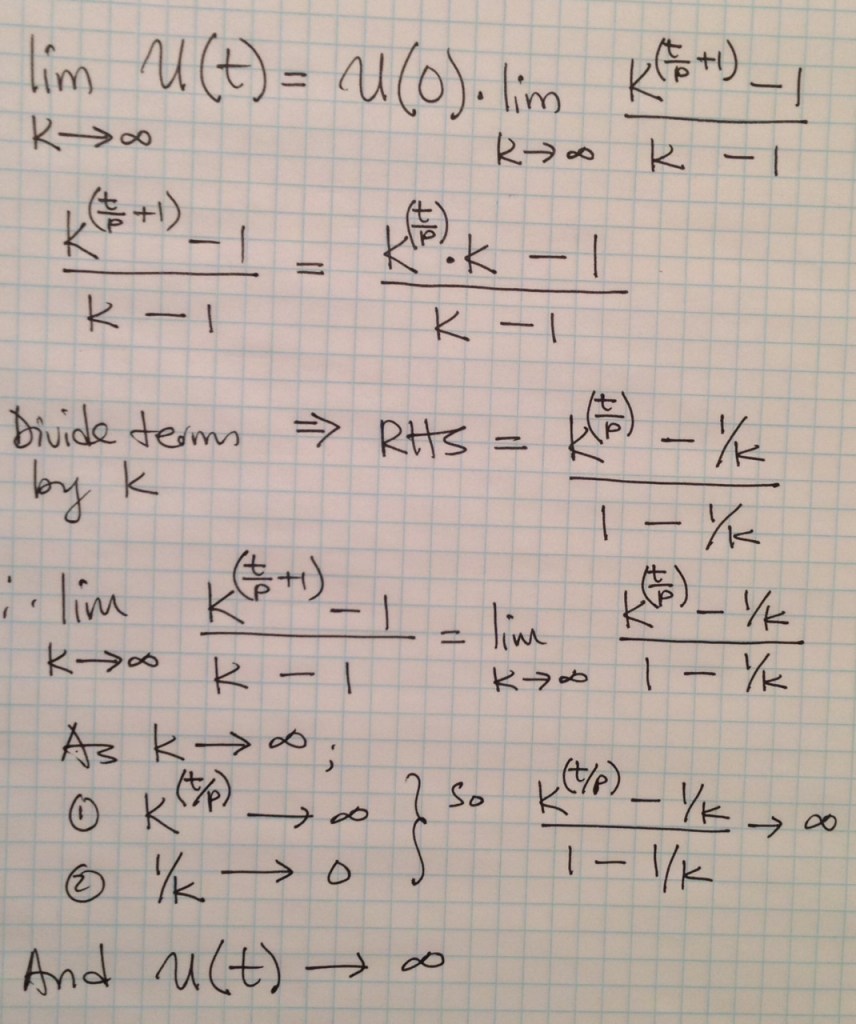

Second, what would we expect to happen to U(t) if we let K become infinitely large and hold everything else constant? As the back of the envelope analysis below suggest we expect the number of users at any given time to become infinitely large as we make the viral coefficient infinitely large.

This bears repeating. There are at least two ways to make the number of users at any given point in time infinitely large. One approach focuses on cycle time and tries to make that as small as possible. The other approach focuses on the viral coefficient and tries to make that as large as possible. Which one should the product developer focus on? That depends. Certain products lend themselves to the approach that focuses on cycle time as the lever. Youtube is a great example, one that David Skok himself uses to make his argument for focusing on cycle time as the driver of viral growth.12 Other products lend themselves more to the approach that focuses on the viral coefficient. Dropbox comes to mind as a product for which it would make much more sense to focus on the viral coefficient as the lever that drives user growth.13

A third driver of viral growth exists, and it is not given enough emphasis in the Skok-Reiss framework. Churn. There are two types of churn. The first type is the instance of the user who signs up for the product, but uses it so infrequently that ultimately that user’s contribution to the growth in total users is negligible. Tactics should be devised to increase that user’s engagement with the product. The second type is the instance of the user who abandons the product altogether soon after adopting it. Efforts should be made to minimize this occurrence. Managing churn is critical because it gives the team of people working on tactics to minimize cycle time or maximize viral coefficient room to run experiments and determine which tactics will work best in accelerating growth in the user base, ultimately compensating for a product’s initially unfavorable cycle time and viral coefficient if that is the situation in which a product finds itself after it has been been launched. Pinterest is often cited as a product that started out with a small viral coefficient and a small user base.14

The Skok-Reiss Virality Model is most frequently discussed amongst investors and startups interested in the topic of viral marketing and viral growth, but it is by no means the only one. In my next blog post on this topic I will examine an approach discussed by Rahul Vohra in a series of posts on LinkedIn, and I will compare his approach to the Skok-Reiss model. After that I will delve into the Bass Model of Technology Diffusion. I’ll wrap up this series on viral marketing by following Valerie Coffman’s footsteps once more by looking to infectious disease modeling for some pointers regarding how one might fix the flaws in the Skok-Reiss model.

Model’s are useful as a guide to the researcher’s thought process, but it is the researcher’s responsibility to examine each model for flaws and weaknesses and then to devise ways to compensate for them in order to reduce the possibility of forecasts that contain large errors.

- Any errors in appropriately citing my sources is entirely mine. Let me know what you object to, and how I might fix the problem. Any data in this post is only as reliable as the sources from which I obtained them. ?

- For example: The Science Behind Viral Marketing, Sep. 15th, 2011 and Lessons Learned – Viral Marketing, Dec. 6th, 2009. Accessed online on Jul. 23rd, 2014. ?

- A Virality Formula, Dec. 29th, 2011. Accessed online on Jul. 23rd, 2014. ?

- 4 Major Mistakes in The Current Understanding of Viral Marketing, Jan. 17th, 2013. Accessed online on Jul. 24th, 2014 ?

- Adapted from Vynnycky, Emilia; White, Richard (2010-05-13). An Introduction to Infectious Disease Modelling (Kindle Locations 930-931). Oxford University Press, USA. Kindle Edition. ?

- For example a monthly unit of time represents 4 cycles if the cycle time is one week. ?

- Ries, Eric (2011-09-13). The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses (Kindle Locations 3008-3012). Random House, Inc.. Kindle Edition. ?

- To see this; Assume K > 0, p > 0, and U(0) > 0. Then substitute increasing values of t into the formula. ?

- Also, certain people might stumble upon the product without an invitation. ?

- Some models of how infectious diseases spread within a population often account for an incubation period, an infectious period, and a pre-infectious or latent period. ?

- For example; marketing, PR, press related to product updates, content marketing with calls to action directed at potential new users who might want to sign up for the product without the benefit of an invitation from an existing user, presentations at conferences etc. ?

- Messaging apps as a family might fall within this camp as well. Examples; WhatsApp, Viber, Kik, KaKaoTalk, Line, WeChat, Momo etc. ?

- It is important to reiterate that neither cycle time nor viral coefficient need to remain constant over a product’s lifetime. In fact, one would argue that there ought to be a team of people whose sole focus is designing ways to reduce the cycle time and increase the viral coefficient. ?

- I have actually heard the argument “Our viral coefficient is higher than Pinterest’s at this stage in their development.” in two or three pitches. An example of discussions about Pinterest are; Steve Cheney, How To Make Your Startup Go Viral The Pinterest Way. Accessed at Techcrunch on Jul. 27th, 2014. You can examine the raw data here. There’s also this discussion on Quora: Why Did It Take Pinterest Such A Long Time To Go Viral? Accessed Jul. 27th, 2014. ?