The 1992 Agreement between the Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN) and the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) remains one of the most significant documents in the history of Nigerian higher education. It was born out of a long-standing struggle by university lecturers who demanded better funding, improved working conditions, and greater autonomy for institutions. Our analyst notes that though signed over three decades ago, its relevance continues to echo in policy debates, strike actions, and the broader conversation about the future of Nigerian universities.

A Blueprint for Reform

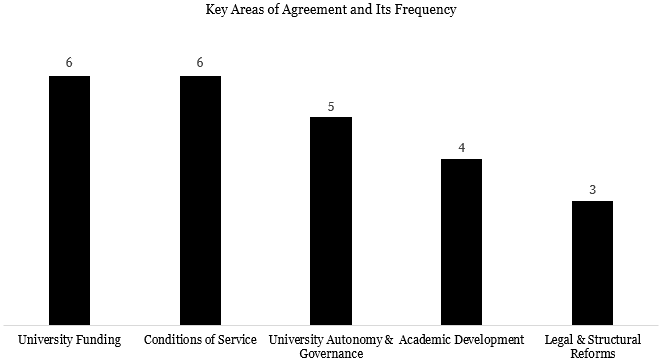

The agreement was a comprehensive attempt to address the deep-rooted challenges facing Nigerian universities. It focused on five major areas. It tackled the issue of funding by proposing a 2 percent education tax on company profits, the creation of a N1.5 billion stabilization fund, and the transfer of government-owned property to universities to help them generate revenue. These measures were designed to reduce the universities’ dependence on federal allocations and encourage financial sustainability.

The agreement emphasized university autonomy. It redefined how vice-chancellors would be appointed, strengthened the role of governing councils, and called for a review of laws that limited academic freedom. This was a critical step toward allowing universities to make decisions independently and manage their affairs without political interference.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 20 (June 8 – Sept 5, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

The conditions of service for academic staff were overhauled. A new salary structure was introduced, along with various allowances such as research, hazard, housing, and transport. The retirement age was set at 65, and provisions were made for sabbatical leave, postgraduate support, and death benefits. These changes aimed to restore dignity to the academic profession and make it more attractive to talented individuals.

The agreement supported academic development through funding for conferences, publications, and duty-free importation of research equipment. It also encouraged universities to engage in consultancy services and provided support for staff schools.

The People Behind the Agreement

The success of the agreement depended on the individuals and institutions involved in its negotiation and implementation. On the government side were ministers, directors, and representatives from key ministries such as education, finance, and labor. ASUU was represented by a team of academics from various universities, led by Dr. Attahiru Jega (now professor), whose leadership helped shape the union’s strategic direction.

These actors played crucial roles in either stabilizing or complicating the agreement. While some worked to implement its provisions, others contributed to delays and inconsistencies. The relationship between these individuals and their institutions influenced how the agreement was interpreted and enforced.

Why the Agreement Still Matters

Despite its ambitious goals, the 1992 agreement has faced uneven implementation. Funding mechanisms like the education tax have struggled with compliance, and the stabilization fund has not delivered the expected results. University autonomy remains contested, with political appointments and legal ambiguities still affecting governance. Salary structures have been eroded by inflation, and many of the academic development initiatives have stalled.

Yet the agreement continues to serve as a reference point in every ASUU-FGN negotiation. It is cited in strike communiqués, policy discussions, and academic forums. More than a historical document, it represents a vision of what Nigerian universities could become if given the right support and freedom to thrive.

A Call for Renewed Commitment

If Nigeria is to build a resilient and world-class university system, it must revisit the spirit of the 1992 agreement. This means fostering genuine collaboration between government and academia, ensuring accountability, and treating education as a vital investment rather than a burden. The agreement reminds us that reform is not just about policy documents but about relationships, trust, and shared responsibility.

The FG-ASUU Agreement of 1992 may be decades old, but its lessons are timeless. It offers a roadmap for rebuilding the university system and a challenge to all stakeholders to honor the commitments that were made.