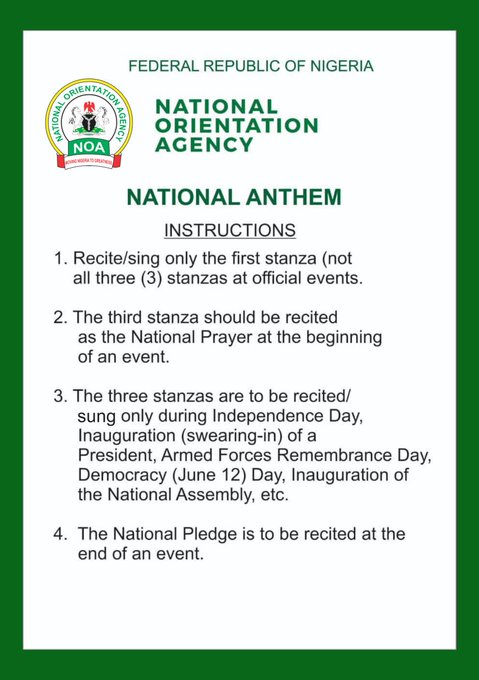

When the National Orientation Agency (NOA) released its notice reminding Nigerians how to properly sing and recite the national anthem and pledge, the intention seemed straightforward. The directive stated that only the first stanza should be used at official events, the third stanza as the national prayer, and all three stanzas on special national occasions. The message concluded with an appeal to citizens to “uphold the dignity and sanctity of our national symbols.”

PUBLIC NOTICE

Correct Application of the National AnthemThe National Orientation Agency (NOA) informs all members of the public to kindly take note of the correct protocol for the rendition and recitation of the National Anthem and Pledge as follows:

INSTRUCTIONS:… pic.twitter.com/WMKptndpbp

— National Orientation Agency, Nigeria (@NOA_Nigeria) October 17, 2025

The aim was to promote patriotism, respect, and discipline. Yet the reactions that followed on social media revealed that official intentions do not always translate into public approval. Instead of widespread acceptance, the announcement generated laughter, irritation, and political commentary. Beneath the humour was a deeper reflection of how citizens perceive authority, belonging, and national pride in present-day Nigeria.

The Message and Its Intention

The NOA’s announcement was an attempt to restore order and reaffirm the country’s sense of identity. It was built on the idea that shared symbols like the anthem can unify people across ethnic and political divides. The language of the notice was firm and patriotic, suggesting that compliance was a moral and civic duty.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 20 (June 8 – Sept 5, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

However, this message landed in a society burdened by economic hardship, insecurity, and public distrust in leadership. For many Nigerians, daily survival takes priority over ceremonial observance. As a result, what was meant to be a patriotic reminder was largely received as a symbol of misplaced government priorities. The reaction showed that even well-meaning communication can lose its power when it seems disconnected from people’s lived realities.

What the Public Really Said

A review of twenty public reactions to the notice gives a clear picture of where Nigerians stand. Only two people, representing about ten percent, supported or accepted the message without complaint. Three respondents, or fifteen percent, were neutral, asking genuine questions about how the new directive should apply in schools or public events. The remaining fifteen, making up seventy-five percent, disagreed, mocked, or dismissed the message entirely.

The disagreements took several forms. Some people expressed disbelief, asking whether any country in the world has a three-stanza anthem. Others laughed at the confusion that came with learning the new version, sharing jokes from orientation camps where people mistakenly sang “Arise O Compatriots.” A number of respondents tied their criticism to politics, predicting that the next government would reverse the anthem. For them, the constant changes in national symbols reflect the instability of leadership rather than the strength of tradition.

Another group questioned the timing and relevance of the announcement. They asked why the government was focused on anthem procedures instead of addressing hunger, insecurity, or inflation. One comment captured this frustration vividly: “Okay, how’s this gonna change the price of Garri in the market?” Some also expressed nostalgia for the more recent anthem, describing “Arise O Compatriots” as more modern, inspiring, and inclusive than the colonial-era version brought back earlier this year.

Rethinking How We Communicate National Values

The key lesson for public institutions is that patriotism cannot be imposed through directives. People do not develop national pride by memorising protocols but by feeling included in a national story that values their contributions and concerns. For the NOA and other government agencies, this means moving from instruction to engagement.

Rather than telling citizens how to sing the anthem, officials should focus on showing why it still matters. Communication that connects national values with visible acts of fairness, security, and opportunity will resonate more deeply than bureaucratic reminders.

True national orientation begins with listening. Nigerians are eager to participate in building the nation, but they want to see sincerity, empathy, and accountability from those who lead. The anthem conversation, far from trivial, offers a glimpse into the country’s emotional temperature. It shows that before citizens can sing together with pride, they must first feel that they are part of a nation that sings with them.