The chips driving the latest breakthroughs in artificial intelligence are running up against a physical wall: heat. Unlike earlier generations of silicon, the new processors powering massive AI workloads generate far more heat, and current cooling technologies are approaching their limits.

Microsoft believes it has found a way past that wall. The company announced it has successfully developed and tested in-chip microfluidic cooling, a technique that channels liquid coolant directly onto silicon to draw out heat far more effectively than today’s widely used cold plate systems.

The company’s lab-scale tests showed microfluidics removed heat up to three times better than cold plates. In one case, the technology reduced the maximum temperature rise of a GPU’s silicon by 65 percent.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 20 (June 8 – Sept 5, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

“With each new generation of AI chips becoming more powerful, they generate more heat,” said Sashi Majety, senior technical program manager for Microsoft’s Cloud Operations and Innovation. “In as soon as five years, if you’re still relying heavily on traditional cold plate technology, you’re stuck.”

Inside the Technology: Cooling Chips from Within

Unlike cold plates, which sit atop chips and are separated by layers that trap heat, microfluidics etches microscopic channels directly onto the back of silicon chips. Liquid coolant flows through these grooves, sweeping heat away from hotspots at the source.

The engineering challenge was steep. The channels are hair-thin, requiring precise etching that balances depth and strength—deep enough to move coolant, but not so deep that the chip risks cracking. Microsoft engineers ran four design iterations in just the past year, working through issues like leak-proof packaging, coolant formulas, etching methods, and chip-manufacturing steps.

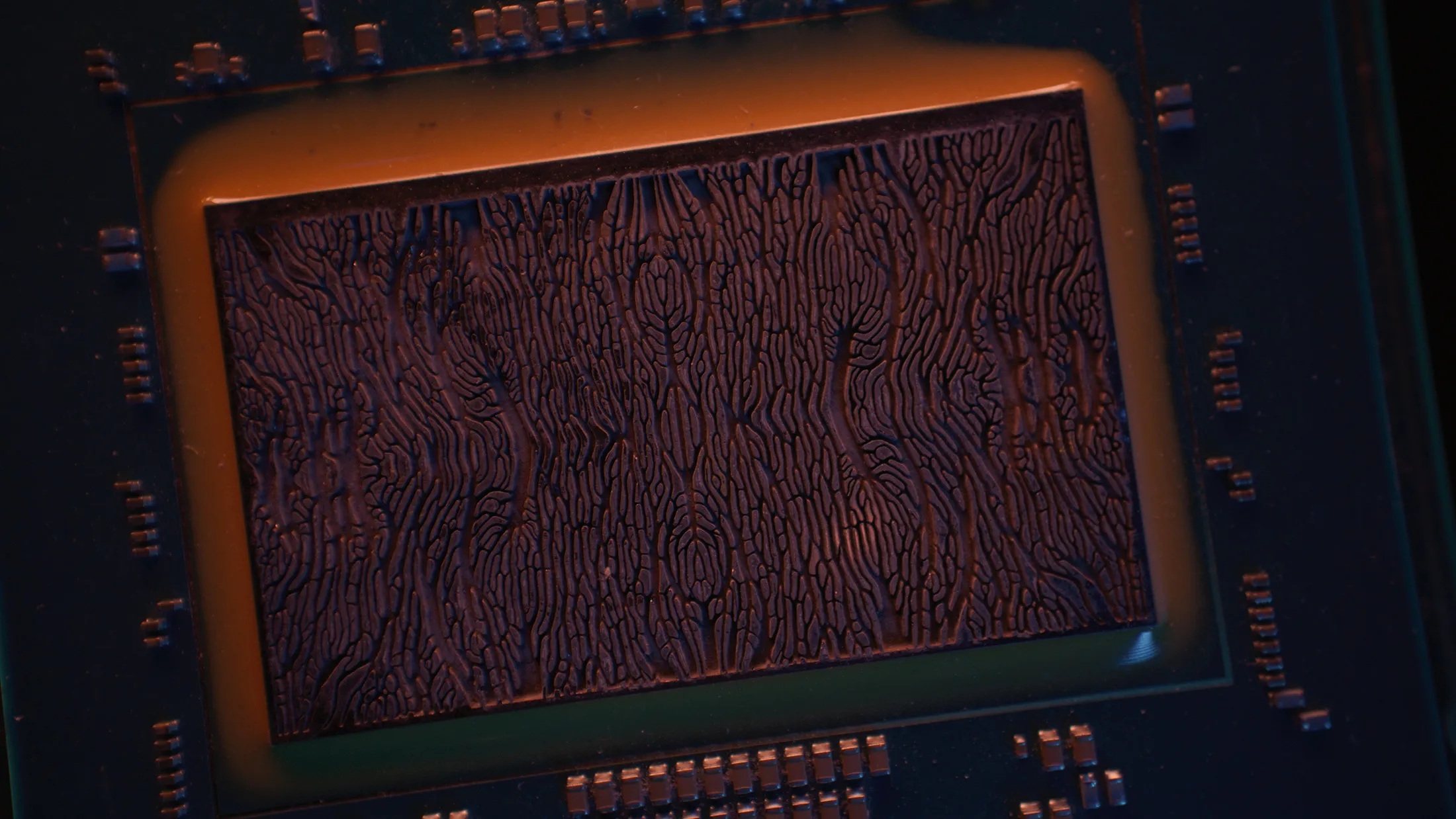

AI played a role in refining the design. Partnering with Swiss startup Corintis, Microsoft used machine learning to test bio-inspired channel patterns resembling leaf veins or butterfly wings, which proved more efficient at cooling hotspots than straight-line grooves.

“Systems thinking is crucial when developing microfluidics,” said Husam Alissa, director of systems technology at Microsoft. “You need to understand interactions across silicon, coolant, server, and datacenter.”

Why It Matters for AI and Datacenters

Microsoft put the new system to the test by simulating a Teams meeting running across core services on a server. Teams is made up of roughly 300 interdependent services, each stressing different parts of a server. During peak demand—like when meetings begin at the top of the hour—servers often risk overheating.

The breakthrough means Microsoft could safely overclock servers to handle spiky workloads without frying chips.

“Microfluidics would allow us to overclock without worrying about melting the chip down,” said Jim Kleewein, technical fellow for Microsoft 365 Core Management. “There are advantages in cost, reliability, and speed.”

Cooling also carries broader implications for datacenter efficiency. Liquid cooling is already more efficient than air, but microfluidics takes it further by bringing coolant directly into contact with silicon. That means coolant does not need to be as cold, reducing the energy required to chill it and potentially improving power usage effectiveness (PUE), a key metric for datacenter efficiency.

It could also allow for denser server packing, since heat currently limits how close servers can sit. More compute in less space translates to lower costs and fewer new datacenter builds—critical at a time when Microsoft is spending over $30 billion this quarter on AI-related capital expenditures.

Unlocking Future Chip Designs

Beyond boosting current GPUs, microfluidics could unlock entirely new chip architectures. Researchers see potential in 3D chip stacking, where layers of silicon are piled vertically like a parking garage. Today, the heat makes this approach impractical. But Microsoft’s prototype design envisions coolant flowing between cylindrical pins in stacked chips, dramatically cutting latency while keeping temperatures in check.

“Anytime we can do things more efficiently and simplify, this opens up opportunities for new innovation,” said Judy Priest, corporate vice president and chief technical officer of Cloud Operations and Innovation.

More powerful, smaller datacenters may also be within reach. Removing heat limits could mean more cores per chip and more chips per rack, boosting compute performance while shrinking datacenter footprints.

Microsoft plans to integrate microfluidics into future versions of its own Cobalt and Maia chips, while also working with fabrication partners to explore production-scale adoption. The company stresses that microfluidics is part of a larger systems-level push—optimizing not just chips, but servers, racks, and software together.

“If microfluidic cooling can use less power to cool datacenters, that will put less stress on energy grids to nearby communities,” said Ricardo Bianchini, corporate vice president for Azure, specializing in compute efficiency.

For Microsoft, the breakthrough is both a technical leap and a competitive one. Its rivals—Google, Amazon, and Nvidia—are also pouring billions into cooling and infrastructure to sustain the AI boom.

But Microsoft is signaling that it doesn’t want microfluidics to remain proprietary. “We want microfluidics to become something everybody does, not just something we do,” said Kleewein. “The more people that adopt it, the faster the technology develops.”

However, Microsoft’s success in embedding microfluidics directly into chips may represent the most significant advance in cooling since the introduction of liquid-cooled plates. As AI workloads surge and chips get hotter, the technology could prove decisive—not only in keeping datacenters running but in shaping the very architecture of future processors.