Earning, saving, investing, and spending are critical aspects of human life. These must be done collectively and personally, using different approaches, before one can boast of living a quality life. Employing a method or multiple methods, however, depends on how individuals perceive the processes for acquiring money before engaging in the subsequent activities.

In this special report, our analyst examines why Nigerians constantly fall into the Ponzi scheme trap despite its high risk of losing substantial investment capital and sometimes earnings. We developed an interest in this problem due to the recent public “panic” surrounding the possible collapse of another scheme, which has been widely reported and considered by many to be another Ponzi scheme.

Before the rise of widespread internet access and social media, smaller, localized schemes likely existed and were often referred to as “wonder banks.” These entities promised unrealistic returns and operated without regulatory oversight, defrauding unsuspecting members of the public.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

Our checks reveal that the Ponzi scheme was introduced into Nigeria through the Mavrodi Mondial Movement (MMM), which originated in Russia in the late 1980s but gained traction in Nigeria in the late 2010s, becoming particularly significant in early 2015. A few years after 2015, the scheme collapsed. Despite this, several similar models emerged, with slight variations in how they promised returns on invested capital. Schemes like Twinkas, Get Help Worldwide, Loom Money, and Ultimate Cycler soon followed.

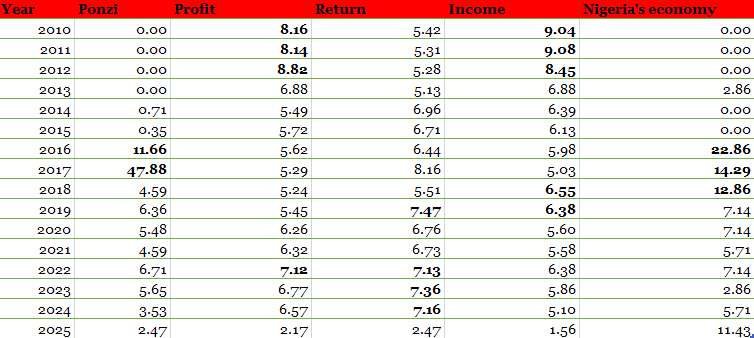

Exhibit 1: Notable Ponzi schemes in Nigeria and the reported or estimated losses

What have been the regulatory responses?

Multiple sources consulted by our analyst reveal that Nigerians have lost over ?500 billion in the past decade due to their engagement in these schemes. The losses, along with public criticism of regulatory agencies, especially the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), have led to the introduction of various measures and the invocation of existing laws. The EFCC, for instance, has consistently warned the public about the dangers of Ponzi schemes.

Laws such as the Investments and Securities Act 2025 are not silent on addressing the problem. The Act prescribes stricter penalties for both direct and indirect actors involved in Ponzi schemes, including hefty fines and lengthy jail terms. Despite the government’s good intentions with the law, non-state actors in the civic space and some citizens have labeled it a ‘paper tiger,’ pointing to its weakness in preventing new schemes from emerging.

Why does Ponzi interest spike despite tighter regulation

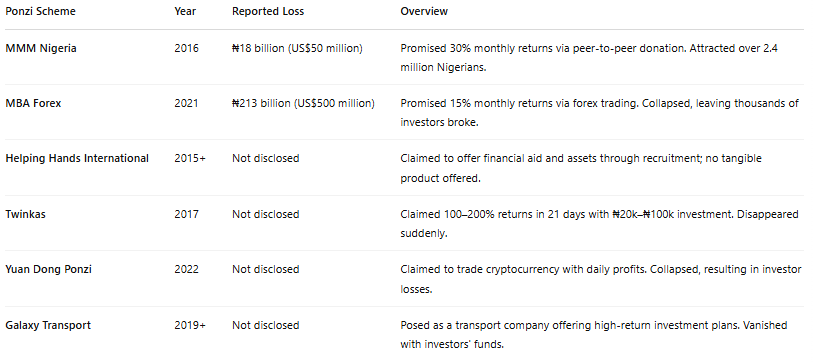

A deep dive into Google Trends data from 2010 to 2025 reveals a compelling and statistically significant connection between interest in Ponzi schemes and broader economic concerns in Nigeria. Public search interest in Ponzi and Nigeria’s economy is positively connected by 53.9%.

This means that nearly a third of the changes in search interest around Ponzi schemes can be explained by shifts in the country’s economic conditions. During periods marked by inflation, unemployment, and financial uncertainty, more people appear to explore Ponzi-like alternatives, not necessarily out of greed, but often as desperate coping strategies.

Exhibit 1: Public search volume of interest from 2010 to 2025 (as of April 13, 2025) in Ponzi and other keywords

The connection grows even stronger when terms like return and income are introduced. With a 57.8% connection and a 33.4% interest in Ponzi schemes in return and income, the data suggests that interest in Ponzi schemes is deeply tied to the public’s concern for income stability and the quest for guaranteed returns. In a climate where job security is fleeting and living costs continue to rise, the allure of high-return promises, even if fraudulent, becomes increasingly difficult to resist.

When the term profit is added to the mix, the connection rises further to 59%. This indicates a dangerous reality: the more people crave profit in an unstable economy, the more likely they are to fall prey to Ponzi-like opportunities. The profit motive, in this case, doesn’t simply reflect ambition; it reflects a survival instinct triggered by systemic economic hardship.

Interestingly, the data also shows that moderate public interest in economic matters corresponds with heightened curiosity about profit, while a higher focus on the economy appears to lower median interest in income-related terms. Our analyst notes that when people engage deeply with macroeconomic concerns, they may begin to question quick-fix income solutions. However, when engagement is shallow or reactive, the desire for profit tends to dominate, regardless of risk.

The consistent interest in “return” across all levels of economic focus points to a deeply ingrained desire for investment gains, a rational impulse in an irrational market environment. This further reinforces the idea that the popularity of Ponzi schemes is not solely rooted in deception, but also in unmet financial expectations and the absence of viable, trusted alternatives.

Ultimately, the positive connection between searches for “Ponzi” and “Nigeria’s economy” reflects more than just curiosity. Our analyst points out that it reflects a rising vulnerability. Periods marked by economic anxiety create the perfect environment for Ponzi schemes to thrive, our analyst adds.

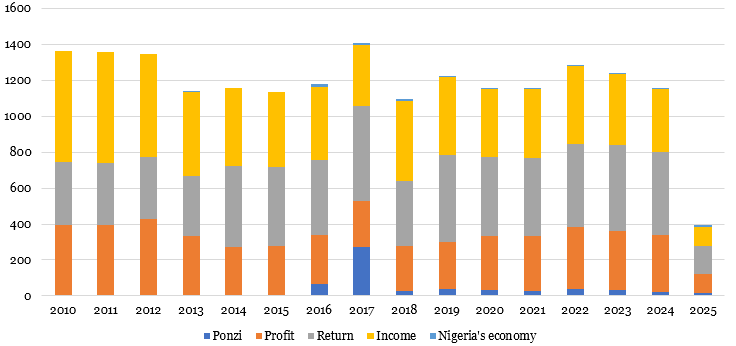

Exhibit 2: Public search volume of interest from 2010 to 2025 (as of April 13, 2025) in Ponzi and other keywords in percentages