The local government crisis in Osun State has become one of the most troubling tests of grassroots democracy in Nigeria. Since February 2025, the state has been trapped in a web of legal disputes, political rivalry, violence, and uncertainty over who truly holds authority at the local level. The longer the stalemate lasts, the more it damages basic service delivery and the trust of citizens in government.

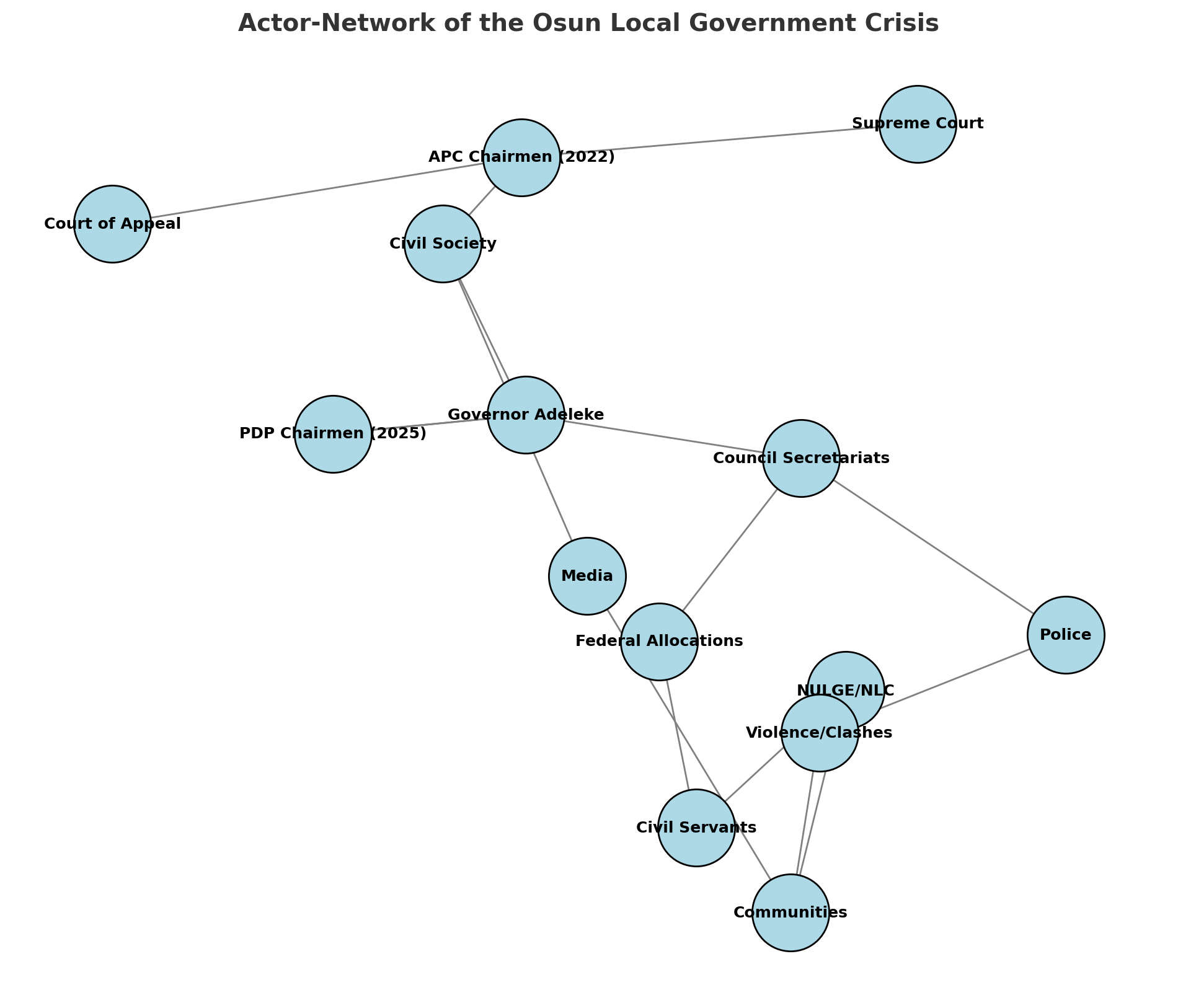

The roots of the crisis can be traced to two competing events. On 10 February 2025, the Court of Appeal gave a judgment that the opposition All Progressives Congress (APC) interpreted as restoring the tenure of local government chairmen elected in 2022. Less than two weeks later, on 22 February 2025, local government elections organised by the state government produced a new set of chairpersons and councillors who were largely from the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP). Governor Ademola Adeleke quickly swore them into office. The APC then directed its earlier chairmen to resume duty, arguing that the court had validated their positions. In that moment, Osun had two sets of officials laying claim to the same councils.

From Clashes to Closures

Tension rose immediately. Across many local government areas, supporters of both sides clashed. Reports of killings and invasions of council secretariats filled the news. At least five people were feared dead, including a serving chairman, while others were injured. Governor Adeleke reacted by ordering all council secretariats shut and placing them under police guard. In one move, the buildings that symbolised power at the grassroots were locked away, leaving both camps unable to exercise full control.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 20 (June 8 – Sept 5, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

With council buildings closed, the battle shifted to the courts, the media, and the flow of funds. The APC insisted that only the Supreme Court could overturn the appeal judgment and demanded that council allocations be released to its officials. The PDP government countered that the February elections were valid and that the swearing in of the new chairmen gave them legitimacy. Civil servants and local government workers found themselves caught in the middle. Their unions, NULGE and the NLC, refused to work under such uncertainty, citing security risks and lack of clarity on who had authority to pay salaries. Their decision effectively paralysed operations at the councils.

The Role of Money and Institutions

The crisis has also been shaped by the movement of money. Federal allocations are the lifeblood of local governments. In Osun, questions about who should receive the funds have become central. Workers have complained of not receiving alerts for months. Civil society groups accuse the state of diverting funds or withholding them unlawfully. The government maintains it is operating within the law and has called for patience. Each statement, each official letter, and each allocation alert or its absence has deepened the mistrust between the two sides.

Beyond money and courts, physical spaces matter. Council secretariats are not just buildings. They are symbols of authority. Whoever controls them is seen to control governance. By locking them, the governor removed that symbol from both sides, but also weakened the visibility of local government as an institution. Communities no longer see their local offices as open places where governance happens. Instead, they see padlocks and police guards. This absence of everyday administration is just as damaging as the violence that sparked the closures.

Finding a Path Forward

The crisis reveals how fragile grassroots democracy can be when legal processes, political competition, and state power collide. On one side, the APC clings to a favourable court judgment as its strongest weapon. On the other side, the PDP relies on the February election and the authority of the governor. Both have legitimate claims, yet neither can translate their claim into undisputed control. This deadlock leaves citizens confused, workers unpaid, and services stalled.

What can be done? the legal ambiguity must be resolved quickly. Only a clear ruling from the Supreme Court can settle whether the 2022 chairmen have any tenure left or whether the 2025 elections stand as final. The state should work with unions and civil society to create a transparent system for tracking and disbursing council funds. Publishing clear records of allocations and spending would rebuild trust. Secretariats must be reopened, at least for basic services, even if managed temporarily by joint committees that include neutral administrators. Dialogue should be prioritised. Political leaders, traditional rulers, and civil groups need to sit together to chart a path away from violence and towards stability.