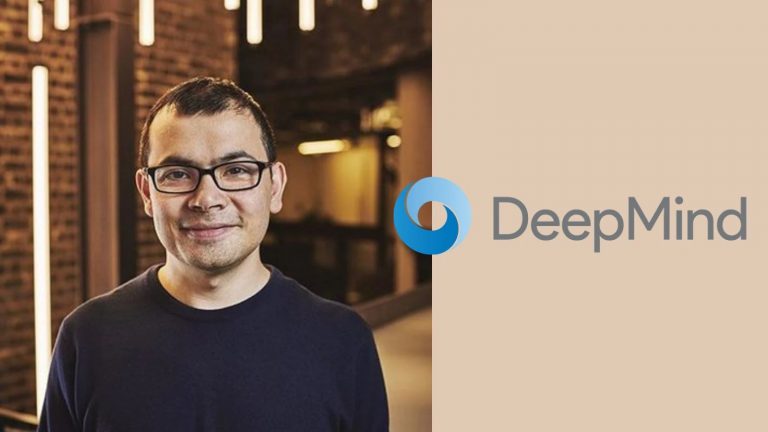

When Google DeepMind quietly brought in Aaron Saunders earlier this month, it wasn’t just another executive hire. It signaled an escalation. Saunders, the engineer who helped give the world its most famous back-flipping, crate-hauling, and occasionally dance-choreographed robots during his years at Boston Dynamics, is now DeepMind’s vice president of hardware engineering. And his arrival suggests the company is no longer content with producing only world-class AI models. It wants machines—real, physical machines—that can use them.

according to Wired, the hire folds directly into CEO Demis Hassabis’ sweeping ambition: to turn Gemini, DeepMind’s flagship model, into something like a robotics equivalent of Android. A base AI system that manufacturers everywhere could load into their humanoids, quadrupeds, warehouse bots, or whatever new chassis emerges next.

“You can sort of think of it as a bit like an Android play […] We want to build an AI system, a Gemini base, that can work almost out-of-the-box, across any body configuration,” Hassabis told WIRED. “Obviously humanoids, but nonhumanoids too.”

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

For Saunders, this is familiar terrain. Before becoming Boston Dynamics’ CTO in 2021, he led some of the company’s most complex engineering efforts, starting with an amphibious six-legged prototype and rising to VP of engineering in 2018. At Boston Dynamics—now majority-owned by Hyundai Motor Company after passing through SoftBank and, earlier, Alphabet itself—he helped steward the hardware behind the company’s signature creations: four-legged dog-sized robots and humanoids capable of highly precise and visually stunning acrobatics.

DeepMind, for its part, has spent years publishing robotics research rooted in large-scale reinforcement learning, imitation learning, and multimodal perception. But the industry’s recent surge of interest in humanoids has shifted that research from an academic project into something commercial. Hassabis said he’s convinced the field is nearing a tipping point. AI-powered robotics, he said, “is going to have its breakthrough moment in the next couple of years, if I was to predict.”

Outside DeepMind’s walls, the momentum has been unmistakable. In the U.S., startups such as Agility Robotics, Figure AI, 1x, and even Tesla have been racing toward humanoid production. Elon Musk said recently he intends to build a million Tesla Optimus robots over the next decade. In China, meanwhile, companies like Unitree have surged ahead on cost and scale; Unitree, based in Hangzhou, has already overtaken Boston Dynamics as the largest supplier of four-legged robots for industries ranging from construction to manufacturing.

Hassabis admitted Unitree’s progress has impressed him. But the true prize for DeepMind isn’t hardware supremacy—it’s cognitive supremacy.

“I’m most interested in the [AI] brain part of it,” he said, emphasizing Gemini’s multimodal structure.

The model’s ability to see, plan, parse language, and reason across different modalities, he argued, makes it especially suited to controlling robotic systems that need to operate in unpredictable physical environments.

That’s where Saunders’ arrival becomes strategically important. His deep, practical understanding of what real robots can and cannot do—how they behave, where they fail, and what they need at the hardware level—gives DeepMind a bridge from system-level AI to embodied intelligence. If Gemini is to become the Android of robotics, it needs precisely the sort of hardware awareness Saunders spent decades refining.

And the timing is advantageous as the components and expertise required to build legged machines have grown dramatically more accessible in recent years. Startups that once would have needed tens of millions in research grants to assemble a basic prototype can now buy actuators, sensors, and control modules off the shelf. The hardware ceiling is dropping while the software ceiling rises—an alignment that DeepMind sees as an opening.

The company, by hiring Saunders, is believed to be signaling that the next frontier for Gemini isn’t just better reasoning or smoother multimodal alignment, but embodiment. A brain that can live in many bodies, across many environments, and adapt on the fly.

Nothing in robotics ever moves as fast as the hype cycles surrounding it. But DeepMind’s latest move suggests the company sees the window opening—and intends to step through it with both hardware sophistication and AI horsepower in hand.