Nvidia chief executive Jensen Huang has framed artificial intelligence–powered robotics as a rare strategic opening for Europe, arguing that the continent’s deep industrial roots give it an edge in what he described as a “once-in-a-generation” technological shift.

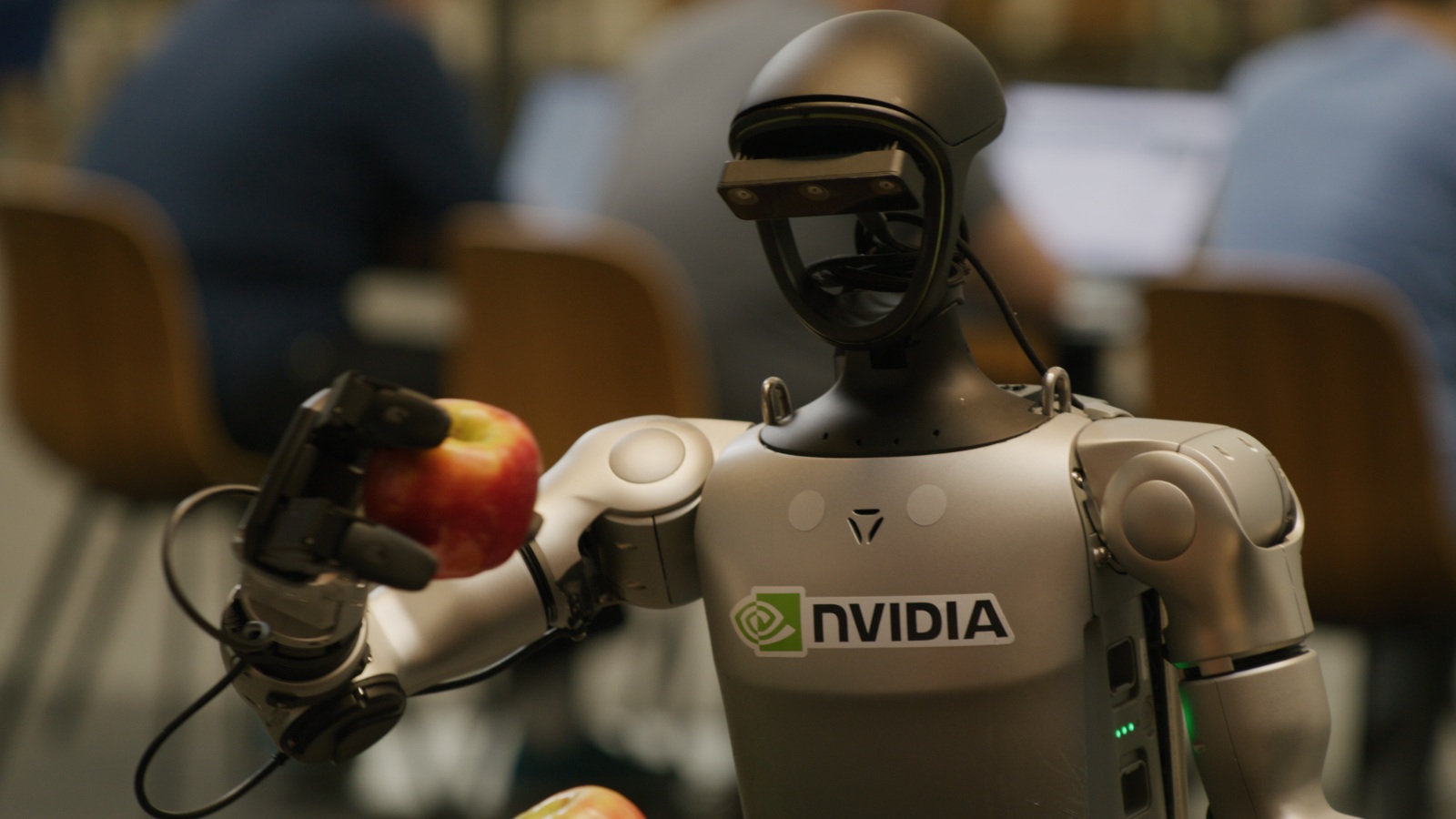

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos on Wednesday, Huang said Europe’s strength in manufacturing positions it to move beyond the software-centric phase of artificial intelligence that has largely been dominated by the United States. The next phase, he argued, lies in what Nvidia calls “physical AI”, systems that combine advanced machine learning with machines that can sense, move, and act in the real world.

“You can now fuse your industrial capability, your manufacturing capability, with artificial intelligence, and that brings you into the world of physical AI, or robotics,” Huang said.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

In doing so, Europe has the chance to “leap past” the software era and reassert itself in a domain where it has long excelled.

His remarks come as attention across both technology and heavy industry shifts toward autonomous robotics. Advances in AI models, simulation, computer vision, and edge computing are rapidly expanding the capabilities of robots, from warehouse automation and factory floors to logistics, mobility, and humanoid systems. This convergence is reshaping long-standing assumptions about productivity, labor, and industrial competitiveness.

Europe’s industrial champions are already moving in that direction. Companies such as Siemens, Mercedes-Benz Group, Volvo, and Schaeffler have announced new robotics projects and partnerships over the past year, often combining proprietary manufacturing expertise with AI software developed by specialist technology firms. These initiatives reflect a broader recognition that robotics may become the main channel through which AI delivers tangible productivity gains in traditional sectors.

The momentum is not confined to Europe. Big Tech firms are also intensifying their push into robotics, underscoring how central the field has become to future growth narratives. Tesla chief executive Elon Musk said in September that 80% of the company’s value would ultimately come from its Optimus humanoid robots. Google’s AI division DeepMind released new robotics-focused models in 2025, while Nvidia itself announced partnerships with Alphabet in March to advance physical AI systems.

Investors are following closely. According to Dealroom, companies building robotics technologies raised a record $26.5 billion in 2025, highlighting growing confidence that the sector is nearing a commercial inflection point after years of promise and limited scale.

Yet Huang was clear that Europe’s ability to capitalize on this opportunity will hinge on a constraint that has increasingly defined the AI race: energy. He said the region must “get serious” about expanding its energy supply if it wants to support the infrastructure required for large-scale AI and robotics deployment.

Europe has some of the highest energy costs in the world, a challenge that has been compounded since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Those costs are becoming a structural disadvantage as AI systems demand vast amounts of electricity to power data centers, training clusters, and real-time inference at the edge.

Huang’s comments echoed those of Microsoft chief executive Satya Nadella, who told the forum a day earlier that energy costs will be a decisive factor in determining which countries succeed in the AI era. For robotics in particular, the energy challenge is twofold: powering the cloud-based intelligence behind the machines and supporting the electrified factories, logistics hubs, and networks in which they operate.

“I think that it’s fairly certain that you have to get serious about increasing your energy supply so that you could invest in the infrastructure layer, so that you could have a rich ecosystem of artificial intelligence here in Europe,” Huang said.

That infrastructure layer is already expanding rapidly. Hyperscalers are racing to roll out AI data centers across the continent, even as grid constraints and permitting delays slow projects in some countries. Huang said the pace of investment shows no sign of easing, describing AI as the “largest infrastructure buildout in human history.”

“We’re now a few hundred billion dollars into it,” he said. “There are trillions of dollars of infrastructure that needs to be built out.”

But if energy bottlenecks persist, Europe risks watching the next wave of AI-driven industrial transformation take shape elsewhere. If they are addressed, Huang’s argument is that the region could turn its traditional strengths into a modern advantage, using robotics and physical AI to anchor growth, competitiveness, and industrial relevance in the decades ahead.