A group of maize farmers stands huddled around an agronomist and his computer on the side of an irrigation pivot in central South Africa. The agronomist has just flown over the pivot with a hybrid UAV that takes off and lands using propellers yet maintains distance and speed for scanning vast hectares of land through the use of its fixed wings.

The UAV is fitted with a four spectral band precision sensor that conducts onboard processing immediately after the flight, allowing farmers and field staff to address, almost immediately, any crop anomalies that the sensor may have recorded, making the data collection truly real-time.

In this instance, the farmers and agronomist are looking to specialized software to give them an accurate plant population count. It’s been 10 days since the maize emerged and the farmer wants to determine if there are any parts of the field that require replanting due to a lack of emergence or wind damage, which can be severe in the early stages of the summer rainy season.

At this growth stage of the plant’s development, the farmer has another 10 days to conduct any replanting before the majority of his fertilizer and chemical applications need to occur. Once these have been applied, it becomes economically unviable to take corrective action, making any further collected data historical and useful only to inform future practices for the season to come.

The software completes its processing in under 15 minutes producing a plant population count map. It’s difficult to grasp just how impressive this is, without understanding that just over a year ago it would have taken three to five days to process the exact same data set, illustrating the advancements that have been achieved in precision agriculture and remote sensing in recent years. With the software having been developed in the United States on the same variety of crops in seemingly similar conditions, the agronomist feels confident that the software will produce a near accurate result.

As the map appears on the screen, the agronomist’s face begins to drop. Having walked through the planted rows before the flight to gain a physical understanding of the situation on the ground, he knows the instant he sees the data on his screen that the plant count is not correct, and so do the farmers, even with their limited understanding of how to read remote sensing maps.

The Potential for Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture

Hypothetically, it is possible for machines to learn to solve any problem on earth relating to the physical interaction of all things within a defined or contained environment…by using artificial intelligence and machine learning.

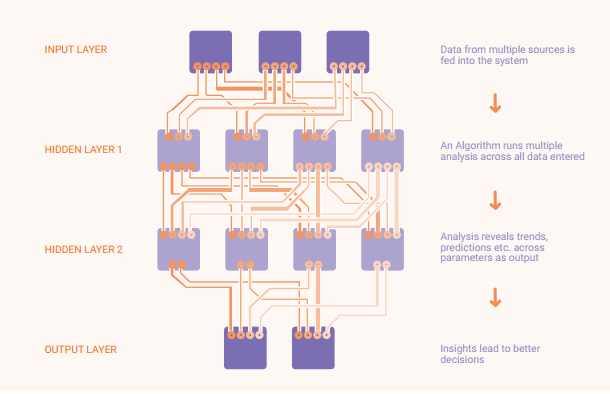

The principle of artificial intelligence is one where a machine can perceive its environment, and through a certain capacity of flexible rationality, take action to address a specified goal related to that environment. Machine learning is when this same machine, according to a specified set of protocols, improves in its ability to address problems and goals related to the environment as the statistical nature of the data it receives increases. Put more plainly, as the system receives an increasing amount of similar sets of data that can be categorized into specified protocols, its ability to rationalize increases, allowing it to better “predict” on a range of outcomes.

The rise of digital agriculture and its related technologies has opened a wealth of new data opportunities. Remote sensors, satellites, and UAVs can gather information 24 hours per day over an entire field. These can monitor plant health, soil condition, temperature, humidity, etc. The amount of data these sensors can generate is overwhelming, and the significance of the numbers is hidden in the avalanche of that data.

The idea is to allow farmers to gain a better understanding of the situation on the ground through advanced technology (such as remote sensing) that can tell them more about their situation than they can see with the naked eye. And not just more accurately but also more quickly than seeing it walking or driving through the fields.

Remote sensors enable algorithms to interpret a field’s environment as statistical data that can be understood and useful to farmers for decision-making. Algorithms process the data, adapting and learning based on the data received. The more inputs and statistical information collected, the better the algorithm will be at predicting a range of outcomes. And the aim is that farmers can use this artificial intelligence to achieve their goal of a better harvest through making better decisions in the field.

In 2011, IBM, through its R&D Headquarters in Haifa, Israel, launched an agricultural cloud-computing project. The project, in collaboration with a number of specialized IT and agricultural partners, had one goal in mind – to take a variety of academic and physical data sources from an agricultural environment and turn these into automatic predictive solutions for farmers that would assist them in making real-time decisions in the field.

Interviews with some of the IBM project team members at the time revealed that the team believed it was entirely possible to “algorithm” agriculture, meaning that algorithms could solve any problem in the world. Earlier that year, IBM’s cognitive learning system, Watson, competed in Jeopardy against former winners Brad Rutter and Ken Jennings with astonishing results. Several years later, Watson went on to produce ground-breaking achievements in the field of medicine, leading to IBM’s agricultural projects being closed down or scaled down. Ultimately, IBM realized the task of producing cognitive machine learning solutions for agriculture was much more difficult than even they could have thought.

So why did the project have such success in medicine but not agriculture?

What Makes Agriculture Different?

Agriculture is one of the most difficult fields to contain for the purpose of statistical quantification.

Even within a single field, conditions are always changing from one section to the next. There’s unpredictable weather, changes in soil quality, and the ever-present possibility that pests and disease may pay a visit. Growers may feel their prospects are good for an upcoming harvest, but until that day arrives, the outcome will always be uncertain.

By comparison, our bodies are a contained environment. Agriculture takes place in nature, among ecosystems of interacting organisms and activity, and crop production takes place within that ecosystem environment. But these ecosystems are not contained. They are subject to climatic occurrences such as weather systems, which impact upon hemispheres as a whole, and from continent to continent. Therefore, understanding how to manage an agricultural environment means taking literally many hundreds if not thousands of factors into account.

What may occur with the same seed and fertilizer program in the United States’ Midwest region is almost certainly unrelated to what may occur with the same seed and fertilizer program in Australia or South Africa. A few factors that could impact on variance would typically include the measurement of rain per unit of a crop planted, soil type, patterns of soil degradation, daylight hours, temperature and so forth.

So the problem with deploying machine learning and artificial intelligence in agriculture is not that scientists lack the capacity to develop programs and protocols to begin to address the biggest of growers’ concerns; the problem is that in most cases, no two environments will be exactly alike, which makes the testing, validation and successful rollout of such technologies much more laborious than in most other industries.

Practically, to say that AI and Machine Learning can be developed to solve all problems related to our physical environment is to basically say that we have a complete understanding of all aspects of the interaction of physical or material activity on the planet. After all, it is only through our understanding of ‘the nature of things’ that protocols and processes are designed for the rational capabilities of cognitive systems to take place. And, although AI and Machine Learning are teaching us many things about how to understand our environment, we are still far from being able to predict critical outcomes in fields like agriculture purely through the cognitive ability of machines.

Conclusion

Backed by the venture capital community, which is now funneling billions of dollars into the sector, most agricultural technology startups today are pushed to complete development as quickly as possible and then encouraged to flood the market as quickly as possible with their products.

This usually results in a failure of a product, which leads to skepticism from the market and delivers a blow to the integrity of Machine Learning technology. In most cases, the problem is not that the technology does not work, the problem is that industry has not taken the time to respect that agriculture is one of the most uncontained environments to manage. For technology to truly make an impact in the field, more effort, skills, and funding is needed to test these technologies in farmers’ fields.

There is huge potential for artificial intelligence and machine learning to revolutionize agriculture by integrating these technologies into critical markets on a global scale. Only then can it make a difference to the grower, where it really counts.

by Joseph Byrum – a senior R&D and strategic marketing executive in Life Sciences – Global Product Development, Innovation, and Delivery at Syngenta..