The U.S. government has granted Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix annual licenses allowing them to import American chip manufacturing equipment into their Chinese factories through 2026, offering limited relief to the South Korean chipmakers as Washington tightens its export control regime.

But the decision is believed to offer short-term operational certainty and signals a more restrictive and conditional phase in Washington’s technology policy toward Beijing.

According to people familiar with the matter who spoke to Reuters, the licenses follow Washington’s move earlier this year to revoke broad waivers that had allowed select global chipmakers to operate in China with minimal regulatory friction. Under the new system, approvals will be granted on a year-by-year basis, giving U.S. authorities greater leverage and oversight over the flow of sensitive semiconductor equipment into the country.

Register for Tekedia Mini-MBA edition 19 (Feb 9 – May 2, 2026).

Register for Tekedia AI in Business Masterclass.

Join Tekedia Capital Syndicate and co-invest in great global startups.

Register for Tekedia AI Lab.

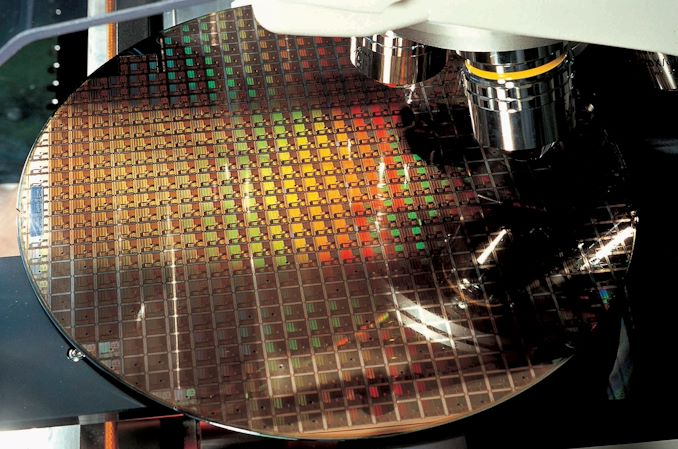

For Samsung and SK Hynix, the approval prevents an abrupt disruption to factories that play a crucial role in the global memory chip market. Both companies rely heavily on China as a production base for legacy memory chips, including DRAM and NAND, which are less advanced than cutting-edge logic chips but remain essential to smartphones, consumer electronics, and data centers. Demand for these products has surged alongside the rapid expansion of AI infrastructure, tightening supplies and lifting prices worldwide.

However, the shift away from the “validated end user” status represents a structural change rather than a temporary policy tweak. That privilege, which will expire on December 31, allowed firms such as Samsung, SK Hynix, and TSMC to import U.S.-origin tools without seeking case-by-case approval. Once it lapses, every shipment of American chipmaking equipment to their China facilities will require an export license, adding layers of uncertainty to routine operations such as tool replacement, capacity optimization, and yield improvements.

Industry executives and analysts say semiconductor manufacturing is uniquely sensitive to regulatory delays. Even mature-node fabs depend on a steady flow of spare parts, upgrades, and servicing tools to maintain efficiency. An annual approval regime means long-term investment decisions could increasingly hinge on geopolitical considerations rather than purely commercial logic.

The move also highlights the Trump administration’s effort to recalibrate U.S. export controls. Officials have been reviewing measures they believe did not go far enough in limiting China’s access to advanced American technology under the Biden administration. While the current licenses stop short of forcing South Korean firms to scale back their China operations, they reinforce a broader message that continued access to U.S. technology is conditional and revocable.

For South Korea, the issue carries economic and diplomatic weight. Samsung Electronics is the world’s largest memory chipmaker, while SK Hynix ranks second globally. Any prolonged disruption to their China operations could ripple through global supply chains and potentially inflate memory prices further, affecting downstream industries from smartphones to cloud computing.

At the same time, Washington appears keen to avoid an outright shock to the semiconductor ecosystem. Granting annual licenses allows the U.S. to tighten controls without immediately undermining allied firms or destabilizing markets. It also preserves negotiating leverage, giving regulators flexibility to adjust approvals based on evolving strategic priorities.

Looking ahead, analysts believe the licenses underscore a growing dilemma for global chipmakers: China remains too large and too deeply embedded in semiconductor supply chains to exit quickly, yet operating there now comes with rising political risk. For Samsung and SK Hynix, the one-year approvals buy time, but they also reinforce the need to diversify manufacturing footprints and reduce exposure to policy shifts.